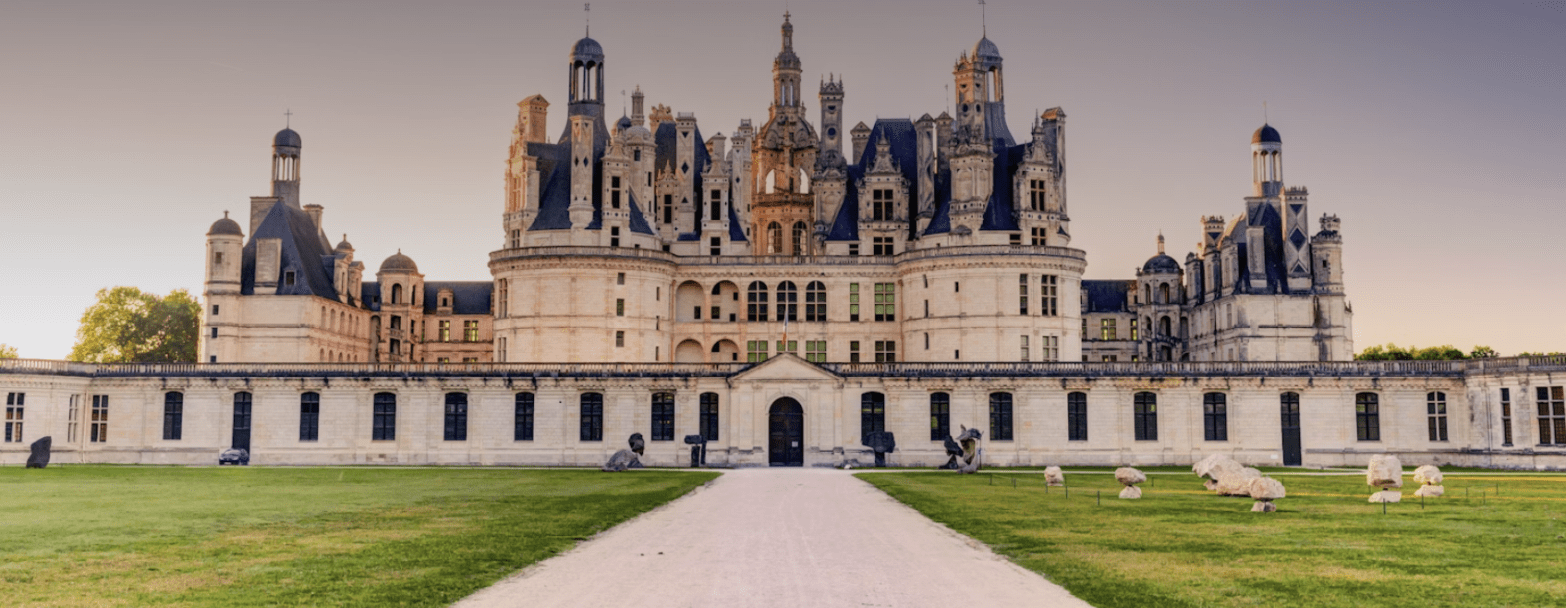

In the heart of the Loire Valley rises one of France’s most extraordinary buildings: the Château de Chambord. Commissioned by François I in the sixteenth century and attributed in part to Leonardo da Vinci’s influence, Chambord is both palace and dreamscape. Its double-helix staircase, fantastical roofline, and forest of turrets and chimneys make it less a residence than a vision in stone—a Renaissance fantasy rendered at monumental scale.

Over the centuries, Chambord has stood as a symbol of French grandeur. But it has also lived another life, one not bound by history books but by the silver screen. Few castles are so immediately cinematic, so perfectly formed for the language of fairy tales. Chambord’s silhouette is a dream in itself, and filmmakers have long recognized its power to conjure enchantment.

Peau d’Âne (1970)

Jacques Demy’s Peau d’Âne brought Chambord into the Technicolor realm of fantasy. Catherine Deneuve, cloaked in surreal costumes by Yves Saint Laurent, moves through the château as if gliding through an illuminated manuscript. The building becomes not merely backdrop but character—its towers and terraces echoing the opulence and strangeness of Charles Perrault’s fairy tale.

In Demy’s hands, Chambord is both magnificent and slightly uncanny: a castle that could only exist in dreams, yet here it stands, vast and real.

La Belle et la Bête (1946)

Two decades earlier, Jean Cocteau reimagined the fairy-tale castle in La Belle et la Bête. While Chambord itself does not appear, its architectural lineage is unmistakable: Cocteau’s dreamscapes echo the fantasy of the Loire châteaux, with Chambord as their archetype. The sweeping staircases, surreal perspectives, and theatrical grandeur of his sets draw directly from Renaissance extravagance.

Chambord, with its spiraling towers and labyrinthine roof, is the blueprint for this cinematic idea of the enchanted château—an architecture that blurs the line between reality and myth.

Architecture as Fantasy

Chambord is unique among the Loire châteaux for the sheer excess of its design. Its roofline is a skyline in miniature, a city of turrets, domes, lanterns, and spires. The double-helix staircase—two stairways winding around one another without meeting—has long been attributed to Leonardo’s influence, further enhancing the château’s aura of mystery.

This is architecture not for comfort but for spectacle, conceived to dazzle, to impress, to stage royal presence. It is no accident that filmmakers of fairy tales have gravitated to Chambord: its architecture is already a fantasy, centuries before the camera arrived.

The Cinematic Dream

On screen, Chambord transcends its history. In Peau d’Âne, it becomes a playground for Demy’s playful surrealism; in Cocteau’s La Belle et la Bête, it hovers as an unseen inspiration, a ghost in the film’s dreamlike architecture. What unites both is the recognition that Chambord is less château than symbol: the ultimate cinematic castle, the image we carry when we imagine turrets against the sky.

More than four centuries after its construction, the château still works as its architects intended: to astonish, to enchant, to make reality seem a little more like a dream. In cinema, it has found its perfect medium.

Visit: https://www.chambord.org/en/