“They lived in squares, painted in circles, and loved in triangles.”

In the genteel drawing rooms of early 20th-century London, respectability was still the reigning order. But in a cluster of shabby houses around Gordon Square in Bloomsbury, a group of young intellectuals tore down the rules. They questioned the empire, mocked Victorian morality, experimented with art, sex, and economics, and in the process remade British culture.

The Bloomsbury Group—writers, artists, economists, critics—were not a formal movement, but their sensibility was unmistakable: candid, modern, witty, liberated. They made conversation an art form and art a conversation. And though derided by some as decadent, their ideas still shape how we live and think.

Beginnings in Gordon Square

The group formed after the deaths of Sir Leslie and Julia Stephen, when their children Virginia, Vanessa, Thoby, and Adrian moved to Bloomsbury in 1904. Their Thursday “at homes” brought together Cambridge-educated friends: Lytton Strachey, sharp-tongued biographer; E.M. Forster, novelist of liberal conscience; John Maynard Keynes, the future economist who would rescue capitalism; and Clive Bell, art critic and theorist of “significant form.”

Here was a generation determined to strip away hypocrisy. They spoke openly about sex, championed pacifism, and dismissed Victorian pieties as so much clutter. Their conversation—brilliant, unbuttoned, irreverent—was itself a revolution.

Painters, Lovers, Experimenters

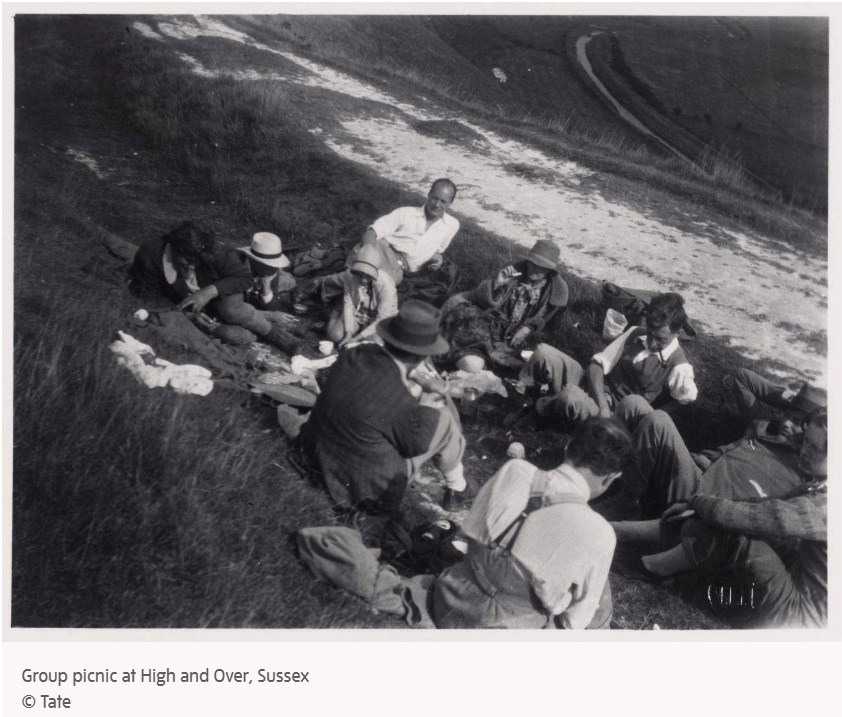

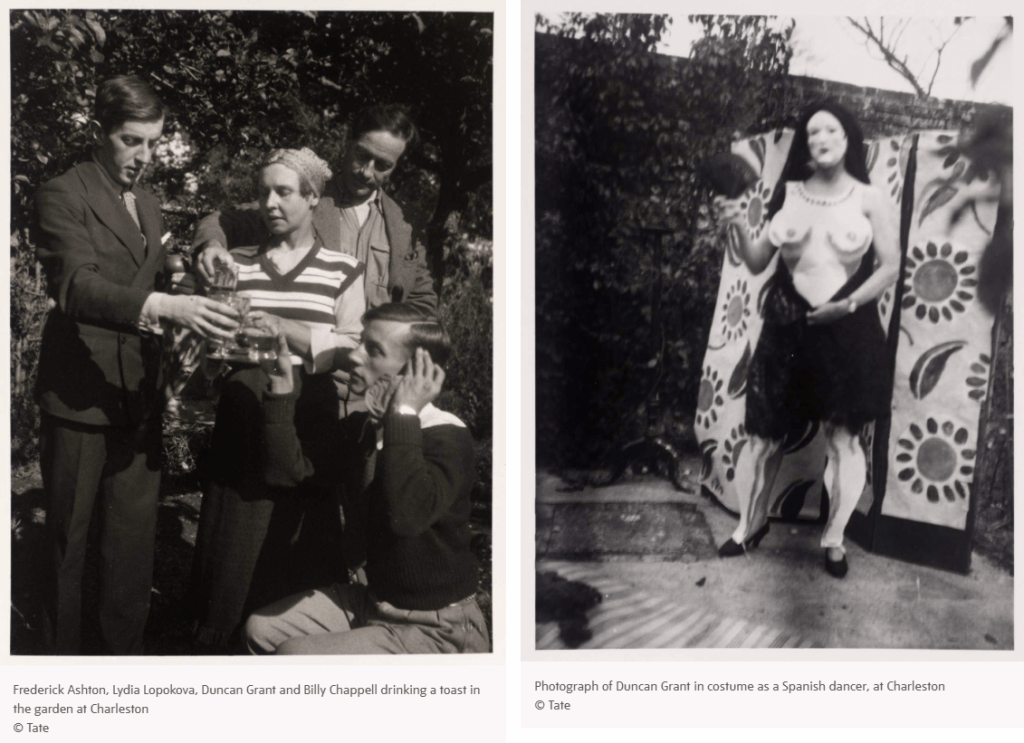

If Virginia Woolf gave Bloomsbury its literary brilliance, her sister Vanessa Bell and their friend Duncan Grant gave it visual form. They rejected Edwardian realism for a Fauvist palette, decorating Charleston Farmhouse in Sussex with riotous murals and textiles, turning domestic space into living artwork.

But Bloomsbury was never only about art—it was about how art and life entwined. The group’s romantic entanglements became legendary: Lytton Strachey proposed to Virginia before admitting he was homosexual; Duncan Grant loved both Vanessa Bell and Maynard Keynes; Vanessa’s marriage to Clive Bell was punctuated by open affairs. For outsiders, it looked scandalous. For Bloomsbury, it was honest.

What They Believed

More than style, Bloomsbury had an ethos: that personal relationships matter more than public duty, that beauty matters, that truth must be spoken even when uncomfortable. Their politics leaned liberal, their economics progressive (Keynes above all), and their art experimental.

Above all, they believed in the primacy of the individual mind. “We were full of experiments and reforms,” Virginia Woolf later recalled, “and our love of truth, our determination to live our own lives, to select our own friends, to make our own society, was fierce.”

Criticism and Influence

Not everyone admired them. To their detractors, Bloomsbury was elitist, incestuous, self-absorbed. D.H. Lawrence sneered at their “beastly Bloomsbury coterie.” Later critics accused them of being too insular, their brilliance limited to their circle.

Yet their influence is undeniable. Keynes reshaped global economics. Forster gave us Howards End and A Passage to India. Strachey reinvented biography with Eminent Victorians. Bell and Grant reshaped British modernism. And Virginia Woolf transformed the novel.

More than individuals, it was their collective vision—that art, love, and intellect could be freely intertwined—that proved radical.

The Legacy of Bloomsbury

A century on, Charleston farmhouse remains a pilgrimage site, its painted walls intact, its gardens blooming with eccentric charm. Woolf’s essays are still assigned in classrooms; Keynes’s theories still underpin government policy. And their tangled loves, once whispered as scandal, now read like a manifesto of sexual honesty.

Bloomsbury gave us permission: to think differently, to live experimentally, to make art inseparable from life.

Quotes

- “Only connect…” – E.M. Forster

- “I am in the mood to uncover the great hypocrisy of our age.” – Lytton Strachey

- “Nothing has yet been said, so far as I know, about the love of friends.” – Virginia Woolf

The Bloomsbury Set lived by conversation, by experiment, by beauty. They believed life itself was the greatest art form—and they lived it, for better and worse, in defiance of the world around them.