Inside the Milanese world of Vincenzo de Cotiis, nothing is ever quite new — and that is precisely the point. The architect and designer has made a career out of listening to surfaces, coaxing stories from stone, plaster, and metal, and reminding us that time itself is the ultimate collaborator.

Step into a Vincenzo de Cotiis interior and you are stepping into a palimpsest. Walls are not scrubbed smooth but left to reveal their age, textures hover between ruin and refinement, and every surface hums with a history that cannot be manufactured. “I was never interested in perfection,” he once said. “I was interested in memory.”

Born in Gonzaga in 1958, De Cotiis trained at the Politecnico di Milano before founding his own studio and gallery with his wife, Claudia Rose. Over the decades, he has established himself as one of Italy’s most distinctive voices, appearing regularly in the AD100 and commanding global attention through projects that range from Venetian palazzi to Parisian flagships.

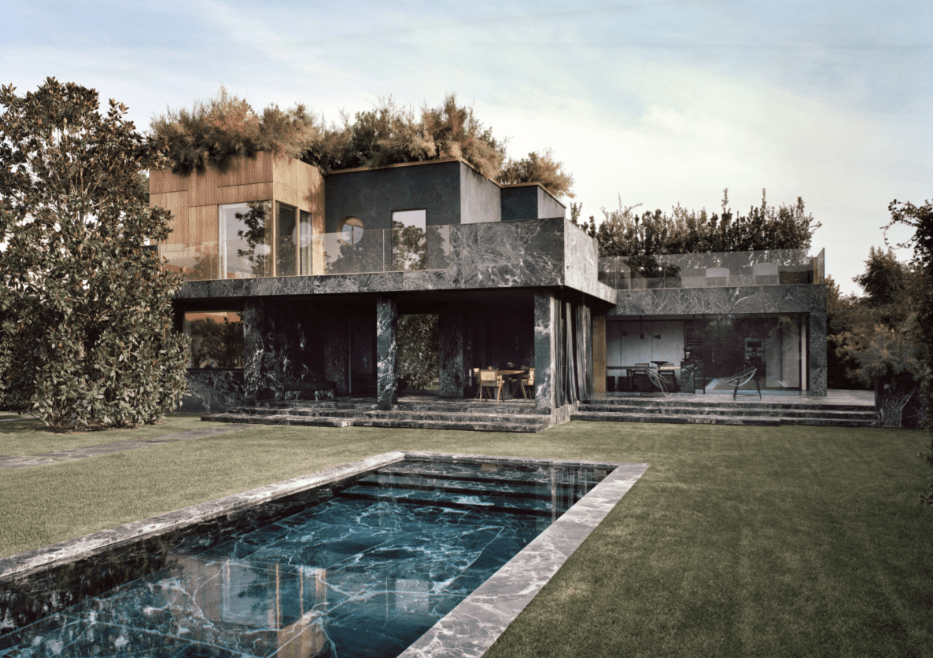

His aesthetic has often been grouped under “collectible design,” but such labels feel too neat. In truth, De Cotiis operates at the crossroads of architecture, art, and archaeology. His furniture pieces—tables in oxidized metal, fiberglass chairs veined with metallic patina, lamps that glow like relics—have the aura of objects unearthed rather than newly made. His interiors, by contrast, are orchestral: spaces of deliberate restraint where old and new sit in taut conversation.

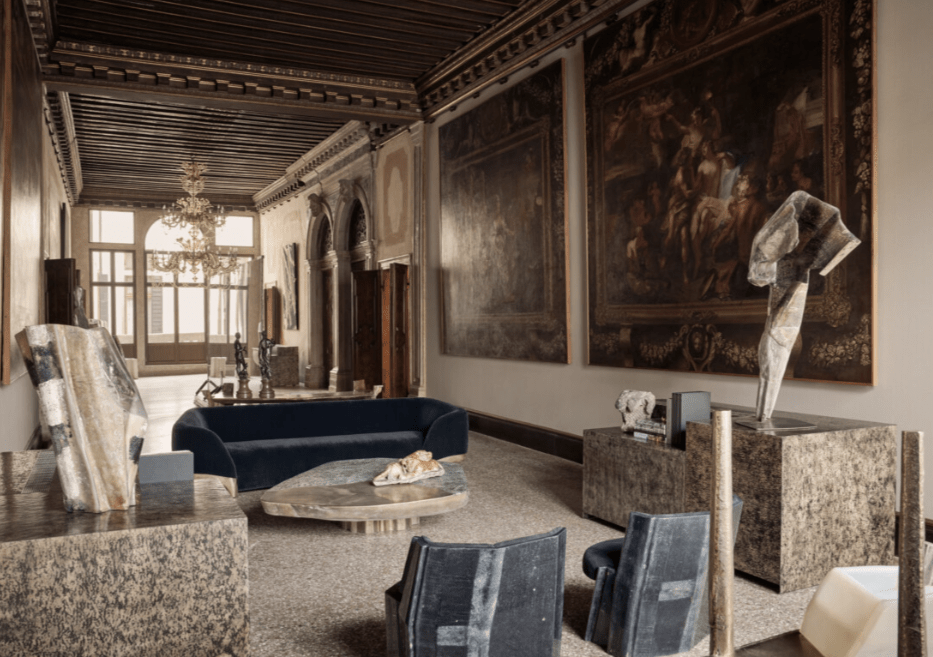

Venice in Dialogue

Take his 2023 transformation of the Palazzo Giustinian Lolin on the Grand Canal. Rather than polishing the 15th-century building into submission, De Cotiis allowed its frescoes, cracked plaster, and softened stuccoes to speak. Into this fragile grandeur he inserted contemporary interventions—marble tables, metal frames, spare lighting—that seem less like intrusions than echoes. The result is not a clash but a dialogue, history and modernity leaning against one another.

The Language of Patina

In retail, he has applied the same sensibility. Burberry’s flagships in London and Paris eschew glossy surfaces in favor of rough stone floors, muted lighting, and fixtures with the appearance of wear. Luxury, here, is not about polish but depth. It is about the feeling that materials have lived, that they will continue to live long after we leave the room.

De Cotiis’s furniture works in a similar register. Exhibited in galleries worldwide, his tables, consoles, and lamps occupy that elusive territory between design and sculpture. A De Cotiis table is not simply a table: it is a study in alchemy, where fiberglass meets bronze, where imperfection becomes elegance.

Heritage and Modernity

At London’s Ladbroke Hall, a Grade-II listed property reborn as a cultural hub, De Cotiis designed the restaurant and boardroom. Here, muted plaster walls, bronze details, and natural woods set the tone, emphasizing calm rather than spectacle. Again, the impulse was not to overwrite history but to extend it—layering the present gently atop the past.

This same principle animates his private commissions: Milanese apartments with plaster left raw, superyacht interiors that seem carved from shadow, always a balance between comfort and austerity, between weight and air.

The Poetry of Imperfection

What makes De Cotiis singular in today’s design landscape is his refusal to participate in the cult of the new. His interiors whisper rather than shout; his objects look excavated rather than fabricated. He is, in a sense, a designer of ruins—though his ruins are polished just enough to live with, poised delicately between fragility and permanence.

“There is hidden painting in everything I do,” he has said. And indeed, to inhabit one of his spaces is to see that painting emerge slowly: a crack in plaster like a brushstroke, a patinated surface like a canvas touched by time.

The De Cotiis Materials Lexicon

Fiberglass

Once a humble industrial material, fiberglass becomes alchemy in De Cotiis’s hands. He layers pigments and metallic powders into its translucent body, creating surfaces that glow as if lit from within. Tables and consoles often appear fossilized, as though dug from a futuristic ruin.

Oxidized Metals

Bronze, brass, and steel are encouraged to age rather than shine. Oxidation, scratches, and uneven coloration are celebrated as part of the design. In De Cotiis’s interiors, a green-tinged bronze panel or a dulled brass surface speaks more eloquently than a polished mirror.

Patinated Plaster

De Cotiis often leaves plaster unfinished, revealing cracks, brushstrokes, or tonal shifts. The effect is archaeological: walls look as if centuries of repainting and wear have accumulated, layered one atop the other.

Stone

Marble, onyx, and limestone appear in his projects not as opulent slabs but as meditative presences. Often muted in color, with visible veining, these stones anchor his interiors in a grounded, elemental weight.

Reclaimed Woods

Rough-hewn timbers, often recycled or salvaged, are incorporated into furniture or architectural frameworks. Their wear is left intact, their knots and irregularities honored. They act as living records of past lives.

Light

Perhaps his most elusive material. Rarely harsh, often diffused, light in De Cotiis interiors behaves like a wash of pigment — falling across textures, revealing imperfections, animating surfaces. In many projects, light itself feels as carefully sculpted as the furniture.