A Style for the Modern Age

Few styles announce themselves with as much clarity as Art Deco. All it takes is a glance: a zigzag façade, a sunburst motif, lacquered furniture, a cocktail shaker with chrome lines sharp enough to slice air. Where Victorian excess whispered nostalgia and Modernism insisted on utility, Art Deco spoke the language of desire. It was the geometry of glamour, the architecture of speed, the design of confidence.

Emerging in Paris just before the First World War and christened at the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, the style soon became a global phenomenon, shaping everything from Manhattan skyscrapers to ocean liners, perfume bottles, and cinema interiors. It was an aesthetic of optimism and luxury, but also one shadowed by economic collapse and war. To understand Art Deco is to understand the promises and anxieties of the twentieth century itself.

Origins: From Paris to the World

The roots of Art Deco stretch back to turn-of-the-century France, when designers like Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann, Jean Dunand, and Paul Poiret began fusing traditional craftsmanship with modern forms. Their influences were eclectic: Cubism’s fractured planes, Fauvism’s bold colors, African and Asian motifs seen through colonial exhibitions, and the sleek curves of industrial design.

The 1925 Paris Exposition was the movement’s coming-out party. Nations competed to showcase a new decorative arts for the machine age. French pavilions dazzled with lacquer, exotic woods, and gilded detail; the Soviet pavilion shocked with Constructivist geometry; American displays hinted at streamlined industrial design. Though the fair’s name lent Art Deco its title, the style was never doctrinaire. It thrived on fusion, adapting itself to whatever industry or geography it touched.

Characteristics: The Language of Deco

What makes something Art Deco?

- Geometry & Symmetry: Zigzags, chevrons, stepped forms, and sunbursts.

- Luxury Materials: Ebony, ivory, shagreen, lacquer, chrome, Bakelite.

- Streamlined Forms: Aerodynamic curves inspired by cars, trains, and planes.

- Motifs of Speed & Progress: Stylized fountains, rays of light, skyscrapers, athletes.

- Eclectic Borrowings: Egyptian lotus columns, Mayan patterns, African masks, Japanese lacquer.

Art Deco was modern, but never austere. Unlike the later International Style, which insisted on “less is more,” Deco said, in effect: more, but sleeker.

The Jazz Age & the Roaring Twenties

Art Deco flourished in the exuberant 1920s. Jazz filled dance halls, Hollywood exported glamour worldwide, and skyscrapers began to puncture city skylines. The Chrysler Building (1930), with its gleaming stainless-steel crown, became Deco’s icon in New York: machine worship transfigured into architecture.

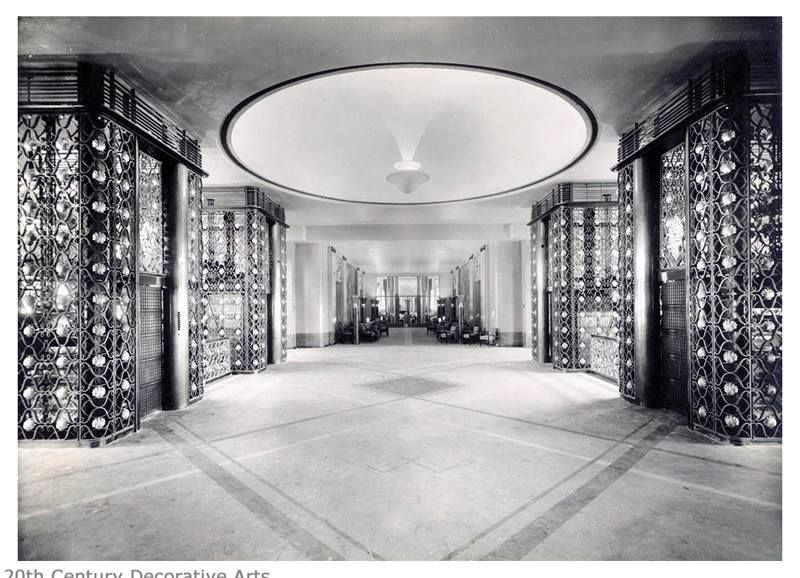

In fashion, designers like Coco Chanel embraced streamlined chic, while Cartier and Van Cleef & Arpels translated Deco into jewelry of platinum, diamonds, and emeralds. Cinema palaces, like Radio City Music Hall, turned Deco into spectacle: sweeping staircases, neon lights, mirrored foyers. The style lent itself to entertainment, where fantasy needed architecture.

The Great Depression & Streamline Moderne

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 altered Deco’s trajectory. Luxury gave way to restraint, and a new variation—Streamline Moderne—emerged in the 1930s. Influenced by aerodynamics and industrial design, it favored horizontal lines, rounded corners, and nautical motifs. Ocean liners like the Normandie, trains like the Burlington Zephyr, and appliances from radios to refrigerators all adopted the streamlined look.

Deco proved adaptable: it could be opulent in Parisian salons, civic in American post offices, or modest in Miami’s pastel hotels. Its democratic reach helped it survive economic hardship while still symbolizing modernity.

Global Deco

One of Art Deco’s strengths was its portability. In Mumbai, architects fused Deco with Indian motifs, creating Marine Drive’s seafront of curving facades. In Shanghai, the Bund filled with Deco banks and theaters, making it Asia’s jazz-age capital. Napier, a New Zealand town rebuilt after a 1931 earthquake, became a rare complete Deco cityscape. Across Latin America, from Mexico City to Havana, Deco blended with local traditions.

Deco’s adaptability was not just aesthetic but political. In Mussolini’s Italy and Stalin’s USSR, Deco monumentalized power; in Roosevelt’s America, it decorated New Deal post offices with murals and motifs of collective optimism. Everywhere, Deco was a language of authority wrapped in glamour.

The Artists and Designers

While architecture gave Deco its skyline, the movement’s richness lay in design.

- Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann created furniture of unparalleled refinement.

- Tamara de Lempicka, with her sleek portraits of women in cool hues, painted the very face of Deco elegance.

- René Lalique turned glass into sensual luxury.

- Erté designed fashion illustrations and costumes that defined Jazz Age glamour.

- Clarice Cliff translated Deco into ceramics accessible to the middle class.

The breadth was astonishing: from the couture houses of Paris to the factories of Ohio, Deco’s forms trickled down every rung of society.

Decline and Survival

By the 1940s, the mood had shifted. War economies demanded austerity; modernism’s minimalism appeared more rational. International Style architects dismissed Deco as ornament. Yet the style never vanished. In Miami Beach, its pastel hotels weathered neglect to become cherished icons. In cinema, the glamour of Deco interiors lived on in black-and-white films, shaping Hollywood’s idea of elegance. By the 1960s–70s, revival interest crowned Deco as vintage chic.

Today, Deco’s influence persists: in fashion runways quoting its geometry, in luxury branding that borrows its typography, in skyscraper silhouettes that still echo its stepped ziggurats. It remains shorthand for a moment when modernity dared to be glamorous.

Timeline: The Arc of Art Deco

- 1908–14: Proto-Deco designers experiment in Paris.

- 1919: Founding of La Société des artistes décorateurs.

- 1925: Paris Exposition; movement christened “Art Deco.”

- 1929: Wall Street Crash; Streamline Moderne emerges.

- 1930–34: Chrysler Building, Rockefeller Center completed.

- 1937: Paris Exposition shows Deco’s maturity and decline.

- 1940s: War halts Deco’s dominance; International Style rises.

- 1960s–70s: Deco revival in fashion and collecting.

The Geometry of Desire

Art Deco is often remembered as the style of jazz and cocktails, of flappers and skyscrapers. But it was more than a look. It was a negotiation between tradition and modernity, luxury and mass production, fantasy and discipline. It offered not utopia, but glamour—an assurance that modern life could be dazzling, not merely efficient.

Stand before the Chrysler Building at dusk, or step into a Deco cinema with mirrored foyers and gilded staircases, and the effect is the same as it was nearly a century ago: the sense that modernity could be theatrical, that progress could gleam. Art Deco is history’s reminder that beauty has always been part of the future.

Architecture & Interiors

- Chrysler Building, New York (1930)

William Van Alen’s gleaming crown of stainless steel — the skyscraper as machine-age cathedral. - Rockefeller Center, New York (1930s)

An urban ensemble of Deco sculpture, murals, and towers — corporate modernity dressed in grandeur. - Radio City Music Hall, New York (1932)

The cinema palace perfected: mirrored foyers, sweeping staircases, and neon spectacle. - Ocean Liner Normandie (1935)

A floating showcase of French Art Deco interiors, from Lalique glass panels to lacquered salons. - Napier, New Zealand (rebuilt 1931)

An entire city reborn in Deco after an earthquake — pastel facades with zigzags and sunbursts. - Marine Drive, Mumbai (1930s)

Curving Deco facades facing the Arabian Sea, fusing Indian motifs with global glamour.

Decorative Arts & Design

- Tamara de Lempicka, Self-Portrait (Tamara in the Green Bugatti) (1929)

Sleek portrait of a woman as modern machine — the very face of Deco elegance. - Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann Furniture (1920s)

Lacquer, exotic woods, ivory inlays — Art Deco luxury distilled into domestic form. - René Lalique Glass (1920s–30s)

Frosted panels, vases, and jewelry — sensual geometry rendered in light. - Erté Fashion Illustrations (1920s)

Stylized silhouettes and shimmering costumes — Deco’s fantasy of the human figure. - Cartier “Tutti Frutti” Jewelry (1920s)

Platinum, diamonds, and carved rubies and emeralds — exoticism meets Parisian refinement. - Clarice Cliff Ceramics (1930s)

Bold, geometric pottery that carried Deco into everyday households.