Among postwar artists, Roy Lichtenstein (1923–1997) most vividly embodies the paradox of high and low culture. His name is virtually synonymous with Pop Art, a movement that sought to collapse the distance between everyday images and fine art, between the mass-produced world of comics, advertising, and consumer culture, and the sanctified walls of museums. Yet Lichtenstein’s work was never merely about replication or parody. Instead, he articulated an art of quotation, a method that transformed the language of mechanical reproduction into a rigorously painterly grammar.

Explore more in our Amazon store

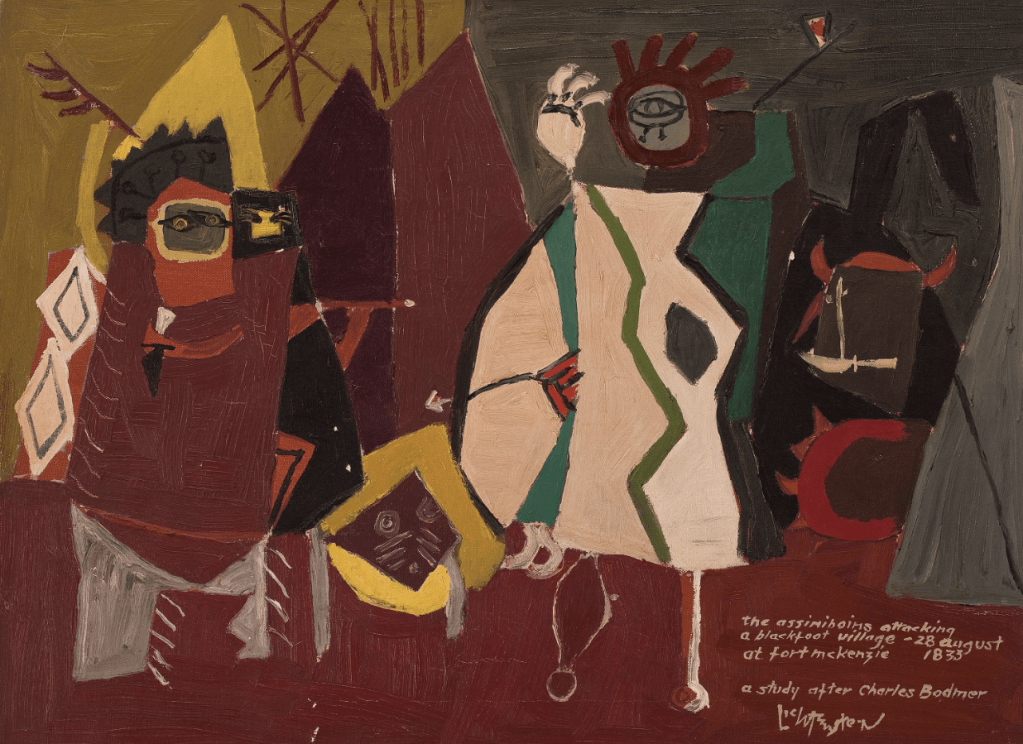

Origins and Early Formation

Born in New York City in 1923, Lichtenstein studied at the Art Students League before serving in the military during World War II. After the war he earned an MFA from Ohio State University, where he was later appointed to the faculty. His early paintings—semi-abstract and indebted to Cubism, Expressionism, and American Regionalism—show little of the comic-book style for which he became famous. What they do show, however, is a restless search for an idiom that could engage the contemporary environment: jazz scenes, cowboys, and even Mickey Mouse appeared in his canvases as early as the 1940s.

This openness to vernacular imagery would become central to his mature style.

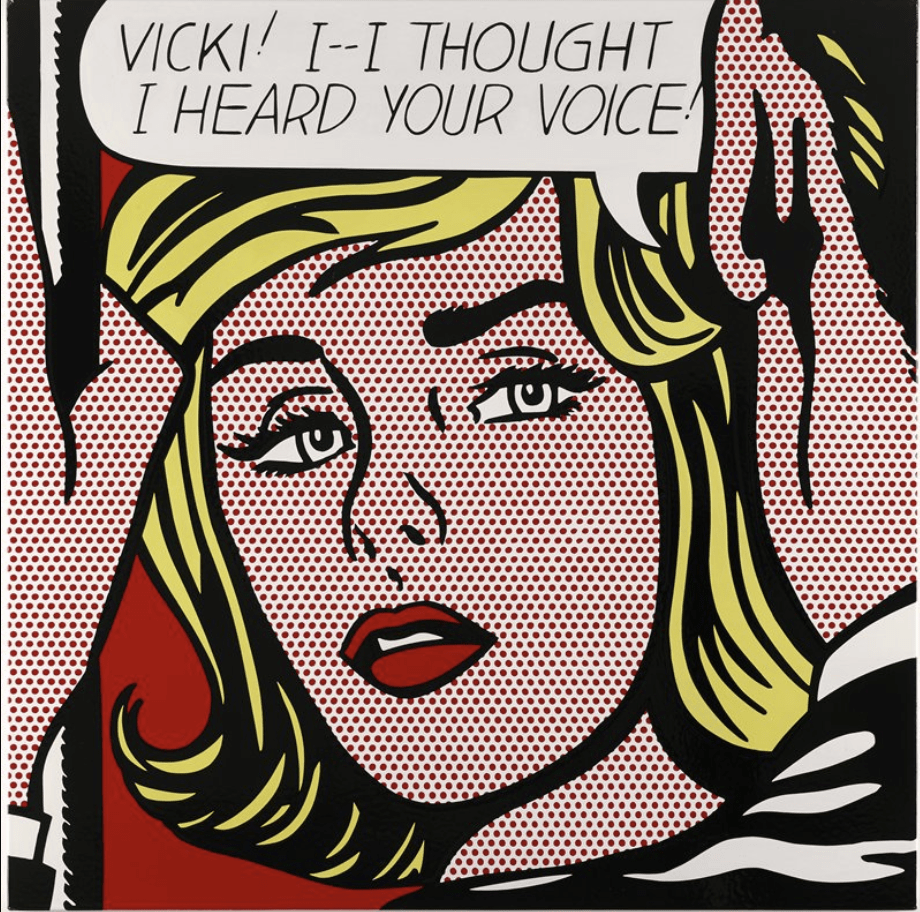

The Comic Strip and the Birth of Style

Lichtenstein’s breakthrough came in 1961, with paintings like Look Mickey, which appropriated comic-book frames of Donald Duck and Mickey Mouse. The source was not simply transplanted; Lichtenstein enlarged it, redrew its contours with thick black outlines, simplified its palette to primary colors, and simulated the mechanical dots of commercial printing through hand-painted Ben-Day dots.

What was radical was not the subject matter itself—comics had long been dismissed as “low” culture—but the deliberate and systematic translation of a mass image into the slow, laborious process of oil painting. The result unsettled critics: was this satire, homage, or theft?

The Ben-Day Dot as Pictorial Device

Central to Lichtenstein’s grammar was the Ben-Day dot, named after 19th-century printer Benjamin Henry Day Jr., whose system allowed shading through small, equally spaced colored dots. In commercial printing, these were machine-applied. In Lichtenstein’s paintings, they were meticulously hand-painted or later applied through stencils.

This reversal—mimicking the mechanical through the artisanal—turned mass reproduction into a meditation on authorship, originality, and the aura of painting. Each dot is both a sign of industrial anonymity and of individual craft, a tension that sits at the heart of his practice.

Quotation, Irony, and the Language of Modernism

Lichtenstein’s work must also be seen in dialogue with modernist abstraction. Paintings such as Brushstrokes (1965–66) or Little Big Painting (1965) parody the gestural marks of Abstract Expressionists like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning. By rendering the heroic brushstroke in cartoon form, he ironized the rhetoric of modernist authenticity.

Later, his “Art History” series directly quoted canonical works: Monet’s Rouen Cathedral, Picasso’s Cubist heads, or Cézanne’s still lifes. Each was filtered through his comic-book idiom, flattening historical distance into a uniform language of dots, lines, and primaries. In this sense, Lichtenstein can be read as a proto-postmodernist, staging what theorist Craig Owens called the “allegory of appropriation.”

Beyond Comics: Interiors, Mirrors, and China

By the 1970s, Lichtenstein expanded his repertoire. His Interiors series presented domestic spaces drawn from advertisements, stylized as idealized mid-century rooms devoid of people but saturated with desire. His Mirror paintings explored reflection and illusion through abstract dot patterns, while his collaborations with porcelain factories in Germany and later his murals and sculptures extended his idiom into new media.

Particularly notable is his Brushstroke series in sculpture, where monumental enamel-painted aluminum forms parody and monumentalize the gestural mark, simultaneously mocking and celebrating painterly tradition.

Critical Reception and Debates

Lichtenstein’s work has long attracted debates about originality and authorship. Critics questioned whether copying comic artists (notably Irv Novick and Tony Abruzzo) without credit constituted exploitation. In response, defenders pointed to his profound transformation of scale, medium, and context, situating his work within the lineage of appropriation central to 20th-century art (from Duchamp’s readymades to Warhol’s silkscreens).

Today, scholars tend to read Lichtenstein not as plagiarist but as theorist in paint: his canvases are about mediation itself, about how images circulate, flatten, and accrue meaning.

Legacy and Institutional Canonization

By the time of his death in 1997, Lichtenstein was fully canonized. Major retrospectives at the Guggenheim Museum (1993) and the Tate Modern / Art Institute of Chicago (2012) affirmed his central place in the narrative of modern and contemporary art. His works command multi-million dollar prices at auction, and his graphic idiom has permeated fashion, design, and advertising—ironically, returning to the mass culture from which it originated.

The Art of Quotation

Roy Lichtenstein’s project was never simply about comics, but about the translation of vernacular images into fine art, about questioning the stability of originality in an age of mechanical reproduction, and about parodying the sanctity of painterly gesture. His work invites us to consider the circulation of images across media and contexts, and to recognize the ways in which art can simultaneously critique and embrace mass culture.

More than any other Pop artist, Lichtenstein turned quotation itself into a style—an enduring lesson in how images mean, repeat, and transform.