Patricia Highsmith’s novels unfold like slow exhalations. They do not shout; they insinuate. A cigarette burns down, a train car hums, a glass of Campari is poured at a café in Naples. Beneath these ordinary gestures lurks unease, a sense that the veneer of civility is about to crack. For Highsmith, menace was not something extraordinary — it was embedded in the everyday.

A Texas Childhood, A European Life

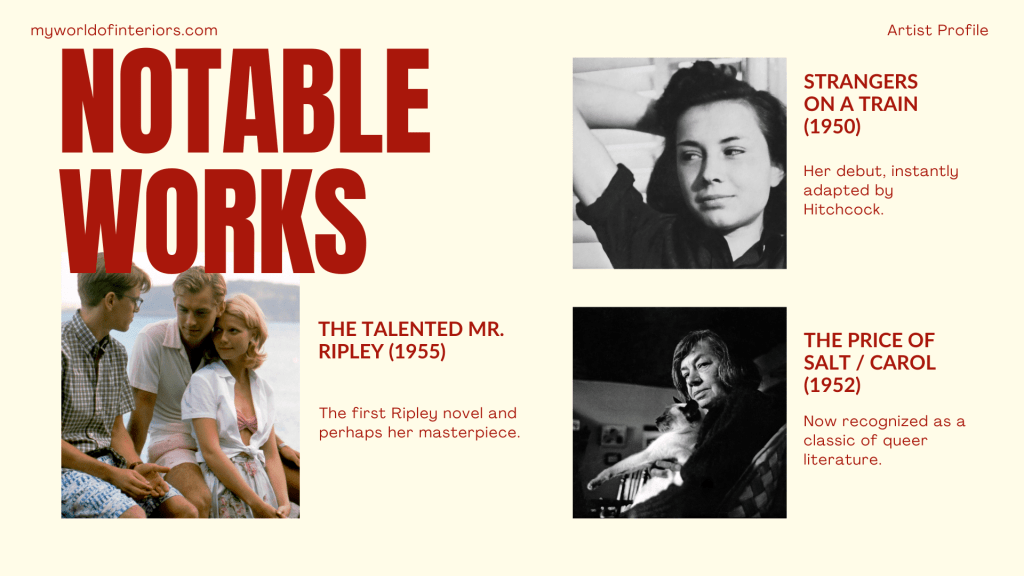

Born in Fort Worth in 1921 and raised partly in New York, Highsmith grew up an outsider: sharp-eyed, solitary, and drawn to the macabre. After studying at Barnard College, she supported herself by writing comic-book scripts, all the while drafting her first novel, Strangers on a Train (1950). Alfred Hitchcock’s film adaptation, released just a year later, gave Highsmith international visibility — though it was only the beginning of a career defined by both acclaim and controversy.

By the mid-1950s, Highsmith had settled in Europe. Paris, Positano, Tegna in Switzerland: these became her landscapes. Her fiction is inseparable from this mid-century European life — the espresso bars, the pensione dining rooms, the Riviera villas where wealth rubbed shoulders with moral rot. For Highsmith, Europe was both liberating and suffocating: a stage set where American exiles pursued pleasure and where violence simmered beneath leisure.

The Ripley Universe

The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955) remains Highsmith’s most enduring creation. Tom Ripley — charming, amoral, protean — embodies her fascination with the slipperiness of identity. An American striver adrift in Italy, Ripley envies and consumes his wealthy friend, then inhabits his life as if slipping into a bespoke suit.

Highsmith’s prose is deceptively cool: precise, unhurried, withholding judgment. Ripley kills, deceives, reinvents himself — yet the reader is drawn into complicity, even admiration. He is not punished in the moralistic manner of crime fiction; he thrives. Across five Ripley novels written between 1955 and 1991, Highsmith allowed her anti-hero to age, to marry, to acquire wealth and comfort — a career criminal as bourgeois gentleman.

The allure of Ripley is inseparable from Highsmith’s rendering of Europe: the cafés of Mongibello, the galleries of Paris, the villas of the French countryside. She wrote these settings with a painter’s eye, every piazza and garden wall vibrating with unease. In her world, beauty is never innocent; it is backdrop to duplicity.

Themes of Menace and Desire

Highsmith’s genius lay in making dread domestic. Violence in her novels rarely bursts forth; it accrues, like condensation on glass. She understood how easily a glance, an offhand comment, or a small deception could open the door to catastrophe.

Her exploration of sexuality and identity was equally radical. The Price of Salt (1952), published under a pseudonym, offered a rare depiction of lesbian love with the possibility of happiness rather than punishment. It became a cult classic, later reissued under her name as Carol. In it, as in Ripley, desire is dangerous but also liberating — a force that bends social order.

The Private Persona

Highsmith herself was as enigmatic as her fiction. Fiercely private, caustically witty, often misanthropic, she lived surrounded by her cats and her notebooks, where she chronicled thoughts with obsessive detail. Friends recalled both her brilliance and her cruelty. She was openly gay but wary of labels, preferring solitude to self-explanation.

The contradictions of her life echo in her work: attraction to Europe yet disdain for expatriate society; desire for intimacy yet preference for isolation; fascination with beauty yet obsession with its corruption.

Legacy

Patricia Highsmith reshaped crime fiction into psychological terrain. She gave us criminals who are not caught, lovers who resist convention, atmospheres thick with ambiguity. Writers from Graham Greene to Gillian Flynn trace debts to her unflinching eye. Filmmakers — Hitchcock, René Clément, Anthony Minghella, most recently the creators of Netflix’s Ripley — continue to mine her work for its blend of style and menace.

Her novels endure not because of elaborate plots but because of the unsettling gaze they direct at us. Highsmith forces the reader into complicity: to sympathize with the killer, to root for the liar, to acknowledge the fragility of morality when desire and envy press against it.

In the end, Patricia Highsmith’s Europe is not a continent on the map but a psychological landscape: the café where envy blooms, the villa where friendship curdles, the seaside town where beauty conceals menace. Her novels remind us that danger is never far away — it is seated at the next table, sipping a drink, waiting for the chance to smile.

10 Essential Works by Patricia Highsmith

1. Strangers on a Train (1950)

Her debut, instantly adapted by Hitchcock. A study in guilt and complicity, where two men agree to “exchange” murders. It established her fascination with the thin membrane separating normal life from crime.

2. The Price of Salt / Carol (1952)

Written under the pseudonym Claire Morgan, this groundbreaking lesbian love story offered rare hope instead of tragedy. Now recognized as a classic of queer literature.

3. The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955)

The first Ripley novel and perhaps her masterpiece. Tom Ripley, an outsider who longs for wealth and acceptance, murders his way into another man’s life. A novel of envy, performance, and moral voids.

4. Ripley Under Ground (1970)

Ripley returns as an art-world manipulator, navigating forgery and fraud. A meditation on authenticity and deception in both life and art.

5. Ripley’s Game (1974)

Often considered the sharpest of the Ripley sequels, here Tom orchestrates murder through manipulation rather than direct action, testing the limits of his own detachment.

6. The Boy Who Followed Ripley (1980)

Ripley befriends a troubled young American in Europe, revealing unexpected tenderness. Highsmith complicates Ripley’s character, blurring morality even further.

7. The Tremor of Forgery (1969)

Set in Tunisia, this novel explores alienation, violence, and the fragility of Western morality abroad. Graham Greene called it her finest work.

8. The Cry of the Owl (1962)

A dark exploration of obsession and surveillance, where a man spies on a woman through her window, only to become entangled in violence and paranoia.

9. The Blunderer (1954)

A mid-career novel that refines her theme of accidental criminals: ordinary men who slide into disaster through weakness and chance.

10. Little Tales of Misogyny (1974, short stories)

A sardonic collection that dismantles stereotypes of women with biting, unsettling irony. Proof that Highsmith’s short fiction was as sharp as her novels.