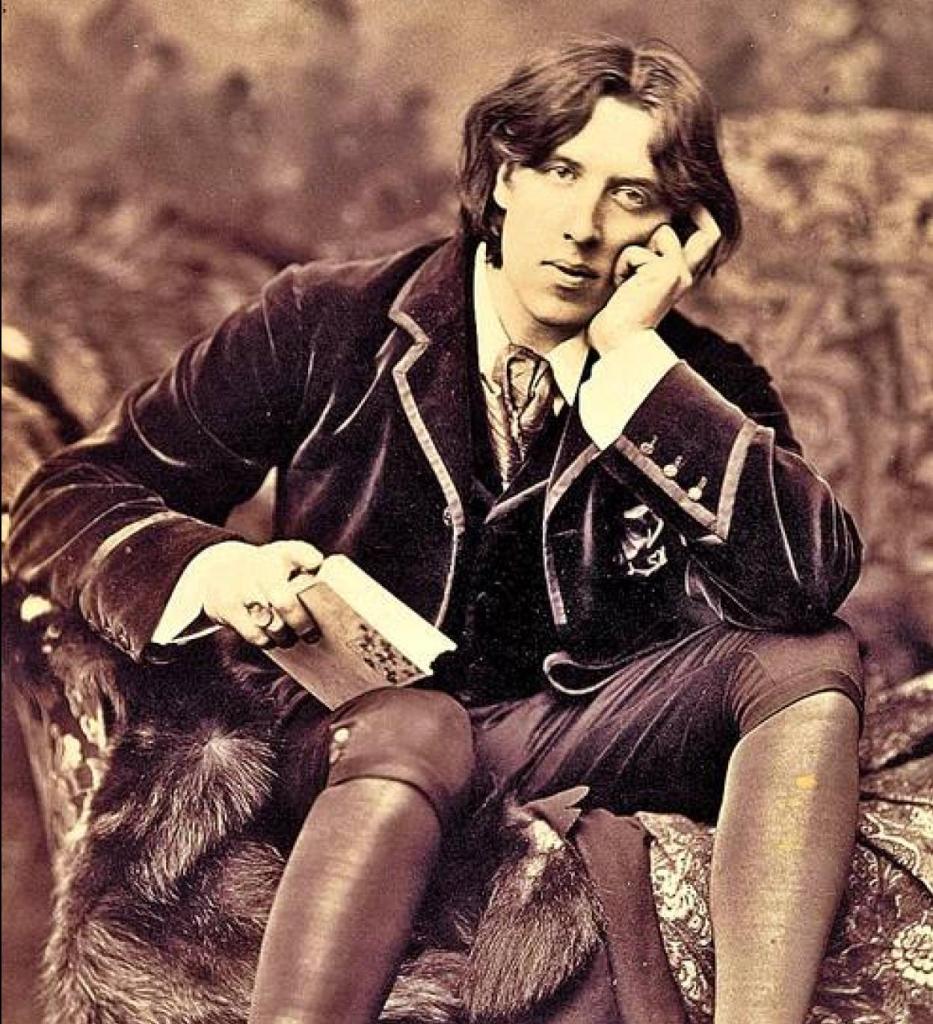

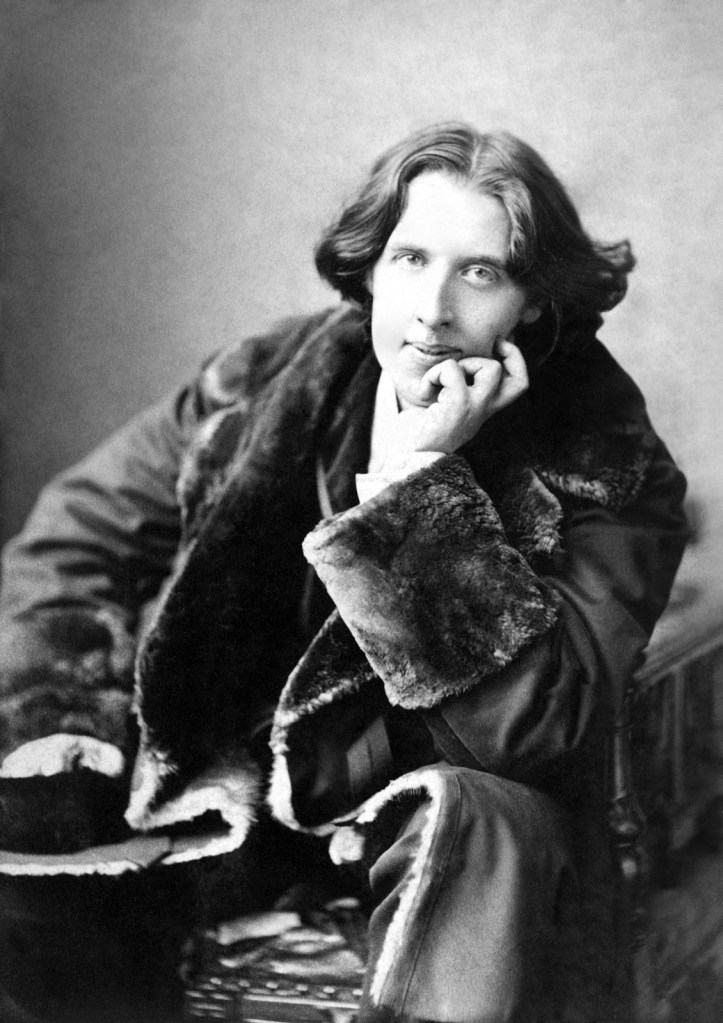

Oscar Wilde once wrote that “one should either be a work of art, or wear a work of art.” Few figures in modern literature have embodied that maxim as completely as he did. Dandy, dramatist, aesthete, wit, martyr: Wilde’s life was not merely lived but staged. He was at once a literary force, a cultural phenomenon, and a cautionary tale of the Victorian world’s mercilessness toward those who dared to transgress its norms.

The Birth of an Aesthete

Born in Dublin in 1854, Wilde grew up in a house where intellect and flamboyance coexisted. His mother, Lady Jane Wilde (known in literary circles as “Speranza”), was a poet and political firebrand; his father, Sir William Wilde, was a celebrated surgeon and folklorist. From this union of radical ideas and aristocratic affectations, Oscar inherited both his appetite for art and his instinct for spectacle.

At Trinity College, Dublin, and later at Oxford, Wilde was shaped by the intellectual currents of the day. He absorbed the philosophy of Walter Pater, who urged his students to burn with “a hard, gem-like flame” — to treat life itself as an aesthetic project. Wilde took this credo and made it literal. By the time he left Oxford, crowned with prizes for his Greek and Latin verse, he was already notorious: peacock feathers in his lapel, paradox on his tongue.

A Career Made of Poses

In 1882, Wilde embarked on a yearlong lecture tour of the United States. It was, in part, a parody of himself: he was mocked in cartoons, lampooned on stage, derided for his velvet suits and sunflower boutonnières. But Wilde leaned into the caricature, understanding instinctively that being talked about — whether in praise or ridicule — was a form of power.

That instinct carried him through the 1880s, when he became London’s most notorious aesthete. He edited The Woman’s World, wrote fairy tales of crystalline melancholy (The Happy Prince and Other Tales), and published essays that danced between irony and conviction. His criticism — especially “The Critic as Artist” and “The Decay of Lying” — made the case that art was autonomous, answerable only to beauty itself, not to morality or social utility. It was a radical creed in a society obsessed with respectability.

Master of the Stage

Wilde’s true ascent came in the 1890s, when he turned to the theatre. Between 1892 and 1895 he produced four society comedies — Lady Windermere’s Fan, A Woman of No Importance, An Ideal Husband, and The Importance of Being Earnest — that skewered Victorian hypocrisy with devastating charm.

In Wilde’s plays, witty paradox masked serious critique. His dandies and grande dames spoke in epigrams — “The truth is rarely pure and never simple” — but beneath the laughter lay a sharp scalpel cutting through marriage, morality, and class. The Importance of Being Earnest (1895) distilled his gift: a trivial comedy that revealed the triviality of the very world it satirized.

At the height of his fame, Wilde was London’s darling. His plays sold out, his name filled gossip columns, his mannerisms were imitated by fashionable young men. He had achieved what he most desired: life as theatre, theatre as life.

The Trial and the Fall

But Wilde’s theatre extended into his personal life. His love affair with Lord Alfred Douglas — “Bosie” — was an open secret, tolerated so long as it remained discreet. In 1895, Bosie’s father, the Marquess of Queensberry, left a calling card at Wilde’s club addressed “To Oscar Wilde, posing sodomite.” Against all advice, Wilde sued for libel.

The suit backfired catastrophically. Queensberry’s defense produced evidence of Wilde’s homosexual relationships, and the Crown prosecuted. The trials that followed were spectacles of their own — Wilde, brilliant yet doomed, trading epigrams with prosecutors, making a final stand for the idea that love was not shameful.

The jury did not agree. Wilde was convicted of “gross indecency” and sentenced to two years of hard labor. Prison broke his health and his fortune. Upon release in 1897, he left England for Paris, where he lived in near-destitution under the name Sebastian Melmoth. He died in 1900 in a shabby hotel room, reportedly quipping, “My wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. One of us has got to go.”

Legacy of a Martyr

If Wilde’s life was tragedy, his afterlife has been triumph. His works never disappeared: The Picture of Dorian Gray has become a staple of Gothic modernism, his plays are revived endlessly, his aphorisms populate anthologies and Instagram captions alike. But more than his art, it is Wilde’s persona that endures — the man who dared to live artfully, who turned his very self into an aesthetic project, who was punished for it and yet made immortal by it.

Wilde’s story is one of paradox. He believed in art for art’s sake, yet his life proved art could never be disentangled from politics and society. He lived as a dandy, yet died as a martyr. He made comedy, yet suffered tragedy.

To read Wilde today is to encounter not only the sparkle of wit but also the shadow of injustice — a reminder that society often destroys the very figures it secretly craves. Wilde himself once said, “A man’s face is his autobiography. A woman’s face is her work of fiction.” His own face — pale, heavy-lidded, mocking and mournful — remains one of the great emblems of modern culture.

Oscar Wilde lived as if life were theatre. The curtain fell too soon, but the performance has never ended.

10 Essential Works by Oscar Wilde

1. The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891)

Wilde’s only novel, and a cornerstone of modern Gothic literature. A meditation on beauty, corruption, and the Faustian bargain of eternal youth, it scandalized Victorian society with its hints of decadence and homoeroticism. Its themes of aestheticism and moral duplicity remain profoundly modern.

2. The Importance of Being Earnest (1895)

The pinnacle of Wilde’s stagecraft: a comedy of manners that weaponizes triviality. Beneath its farcical plot of mistaken identities lies a devastating satire of Victorian respectability. Its epigrams are so embedded in culture they now feel proverbial.

3. Lady Windermere’s Fan (1892)

Wilde’s first major play, blending social comedy with moral paradox. The line “We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars” remains one of his most quoted, crystallizing his gift for combining wit with philosophical resonance.

4. An Ideal Husband (1895)

A political comedy about blackmail, marriage, and public morality. Wilde interrogates the Victorian obsession with honor and hypocrisy, offering a portrait of a society where appearances matter more than truth.

5. A Woman of No Importance (1893)

Often considered his weakest comedy, but vital in its critique of gender roles. It anticipates modern feminist readings with its portrayal of double standards in morality between men and women.

6. Salomé (1893, published in French)

A symbolist one-act play written originally in French, famously illustrated by Aubrey Beardsley. It captures the fin-de-siècle fascination with decadence and orientalism, and became iconic through Richard Strauss’s operatic adaptation.

7. The Happy Prince and Other Tales (1888)

Wilde’s fairy tales for children are suffused with melancholy and moral depth. “The Happy Prince,” “The Selfish Giant,” and others reveal his ability to blend simplicity of form with piercing social critique and pathos.

8. De Profundis (1905, published posthumously)

A letter written during his imprisonment to Lord Alfred Douglas. Part love letter, part spiritual meditation, part artistic manifesto, it shows Wilde at his most vulnerable and self-reflective.

9. The Ballad of Reading Gaol (1898)

Wilde’s last major work, a long poem born of his prison experience. It combines compassion for fellow prisoners with a stark indictment of the brutality of the penal system. Its refrain — “Yet each man kills the thing he loves” — is unforgettable.

10. The Critic as Artist (1891)

An essay in dialogue form that crystallizes Wilde’s aesthetic philosophy. Here, he argues that criticism is not secondary to art but a creative act in its own right. It remains one of the finest statements of “art for art’s sake.”