In the cinematic landscape of the past quarter-century, few directors have crafted a style so immediately recognizable — and so obsessively imitated — as Wes Anderson. His frames are dioramas, his colors symphonies, his characters misfits in corduroy and eyeliner. To watch a Wes Anderson film is to step into a world where every object, gesture, and line of dialogue has been considered, calibrated, and placed with the precision of an architect designing a miniature city.

A Texan in Paris

Wesley Wales Anderson was born in 1969 in Houston, Texas, the second of three brothers. His parents’ divorce when he was eight would become an enduring theme in his work: fractured families, precocious children, and absent fathers.

At the University of Texas, Anderson studied philosophy and met Owen Wilson, a kindred spirit with whom he began writing screenplays. Their short film Bottle Rocket (1994) caught the eye of James L. Brooks, leading to a feature-length debut. Though it barely made a dent at the box office, Bottle Rocket announced a new voice in American cinema: witty, tender, and meticulously offbeat.

Anderson has since become something rarer than an acclaimed director: a cultural force. His films are referenced in fashion editorials, hotel branding, coffee-table books, and Instagram feeds tagged “Accidentally Wes Anderson.” Yet beneath the whimsy lies something more enduring: an art of nostalgia, memory, and loss.

A Cinema of Symmetry

Anderson’s process is famously exacting. He storyboards every frame, often down to the millimeter, before a camera rolls. Sets are custom-built to his specifications — dollhouse interiors, painted backdrops, pastel deserts. The camera moves with choreographed elegance: whip pans, lateral tracking shots, overhead tableaux.

Dialogue is deadpan, humor dry. Yet behind the stylization, his characters are often wounded: children abandoned, adults estranged, communities in decline. The emotional weight lies in the dissonance between the quirk and the ache.

Recurring collaborators — Bill Murray, Jason Schwartzman, Tilda Swinton, Owen and Luke Wilson — populate his films like a repertory troupe, their familiar faces reinforcing the feeling that Anderson’s work is one vast interconnected storybook.

Films in Focus

Bottle Rocket (1996)

A whimsical crime caper co-written with Owen Wilson. Rough around the edges, but already showcasing Anderson’s fascination with loyalty, failure, and eccentric schemes.

Rushmore (1998)

Anderson’s breakthrough. Jason Schwartzman plays Max Fischer, a precocious teenager entangled in a love triangle with his teacher and a disillusioned industrialist (Bill Murray). The British Invasion soundtrack, theatrical staging, and bittersweet humor crystallized Anderson’s style.

The Royal Tenenbaums (2001)

A sprawling portrait of a dysfunctional New York family narrated with literary detachment. Gene Hackman’s Royal Tenenbaum, Gwyneth Paltrow’s Margot, Luke Wilson’s Richie — all children of lost promise, their wardrobes as iconic as their melancholy. A Salinger novel come to life, it established Anderson as a cultural touchstone.

The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (2004)

A tribute to Jacques Cousteau, starring Bill Murray as an eccentric oceanographer. Quirky uniforms, stop-motion sea creatures, and David Bowie songs sung in Portuguese by Seu Jorge. Polarizing at the time, it has since gained cult reverence.

The Darjeeling Limited (2007)

Three brothers travel across India by train in search of spiritual renewal. A study in grief, family, and reconciliation, wrapped in exquisite design and saturated color.

Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009)

Anderson’s first foray into stop-motion animation, adapting Roald Dahl with artisanal care. Hand-crafted textures, witty dialogue, and George Clooney’s dapper fox made the film both critically acclaimed and deeply personal — Anderson found in animation the purest outlet for his obsession with detail.

Moonrise Kingdom (2012)

A tender ode to youthful rebellion. Two runaway children on a New England island, scout uniforms and portable record players in tow. A bittersweet reminder that childhood love can feel larger than life itself.

The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)

Perhaps Anderson’s magnum opus. A nested narrative set in a fictional European republic, anchored by Ralph Fiennes’ brilliant concierge Gustave H. Inspired by the writings of Stefan Zweig, it is both comedy and elegy for a vanished world. Awarded four Academy Awards, it confirmed Anderson’s place in the cinematic canon.

Isle of Dogs (2018)

Returning to stop-motion, Anderson sets his tale in a dystopian Japan where dogs are exiled to a trash island. Quirky, allegorical, and visually stunning, it explores loyalty, exile, and political manipulation.

The French Dispatch (2021)

An anthology film paying homage to The New Yorker. Each vignette celebrates art, exile, and eccentricity, with Anderson’s signature formal playfulness at its peak.

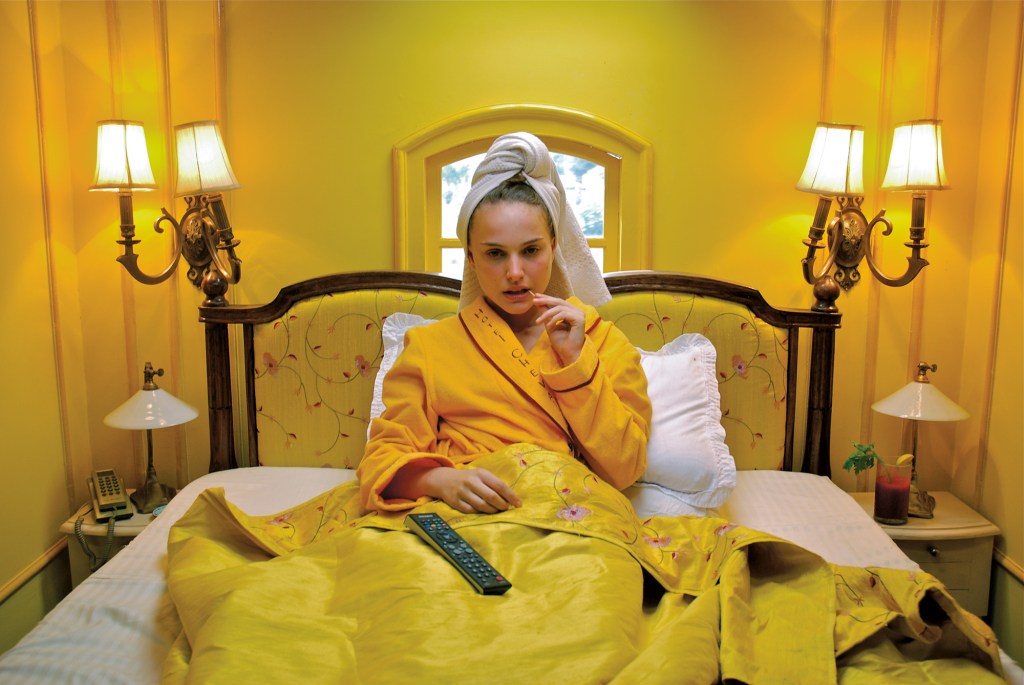

Asteroid City (2023)

Set in a fictional desert town in 1950s America, the film is a play within a play, a meditation on grief, artifice, and meaning. Pastel skies, symmetrical motels, and atomic paranoia merge into a portrait of mid-century anxiety refracted through Anderson’s lens.

The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar (2023)

A Netflix short adapting Roald Dahl, returning Anderson to miniaturist perfection. Meta-narration, precise staging, and Anderson’s signature theatricality distilled into under forty minutes.

The Phoenician Scheme (2025)

An espionage-black comedy that pushes Anderson into new tonal territory. The film follows a charismatic tycoon (Benicio del Toro) whose carefully curated life unravels as he enlists his estranged daughter (Mia Threapleton, playing a nun) in a last-ditch scheme to protect his legacy. Anderson’s hallmarks are all present — immaculate symmetry, curated color palettes, and a repertory cast — but here they’re refracted through the lens of intrigue and betrayal. With cinematography by Bruno Delbonnel and a score by longtime collaborator Alexandre Desplat, the film demonstrates Anderson’s ability to evolve while remaining unmistakably his own.

The Anderson Legacy

Wes Anderson is more than a filmmaker — he is an aesthetic unto himself. His work has reshaped not just cinema but visual culture: hotel lobbies, fashion campaigns, even tourism boards borrow from his pastel symmetry. Yet beyond the imitation lies his enduring gift: a cinema of longing. His characters — fatherless children, has-been geniuses, lonely foxes — remind us that loss and nostalgia are inseparable from beauty.

Where Coppola whispers, Anderson orchestrates. Where she frames silence, he builds symphonies of design. Yet both belong to the same generation of filmmakers who redefined what “independent cinema” could mean at the turn of the millennium.

To step into Wes Anderson’s world is to believe, if only for two hours, that life might be arranged with balance, color, and order. And yet, he reminds us, even the most symmetrical world cannot stave off sorrow — it can only render it beautiful.