When Sofia Coppola released The Virgin Suicides in 1999, critics marveled at the quiet assurance of her debut. Here was a director who seemed uninterested in grand gestures or dramatic flourishes. Instead, she let atmosphere carry the story: gauzy light, suburban lawns, the ephemeral melancholy of adolescence. In many ways, Coppola’s first film announced not just a career but a worldview — one where the spaces between words, the silence of a hotel room, or the pale blush of a Versailles salon said more than dialogue ever could.

Born into Cinema

Sofia Carmina Coppola was born in 1971 into a family where cinema was the air one breathed. Her father, Francis Ford Coppola, reshaped American film with The Godfather trilogy and Apocalypse Now; her mother, Eleanor, documented it all with her camera. She grew up surrounded by actors, editors, and cameramen, spending her childhood partly in hotels and on location sets.

That privilege, however, came with scrutiny. Her ill-fated acting role in The Godfather Part III (1990) was mercilessly criticized, and Coppola herself became a symbol of Hollywood nepotism before she’d ever directed a frame. Yet out of that trial by fire, she forged a uniquely delicate voice — one that stood apart from the bravura of her father’s generation.

A Cinema of Interior Lives

Coppola’s films are less about plot than mood. She captures emotional states with the eye of a photographer: framing her characters at windows, drowning them in soft light, or isolating them within cavernous interiors. Her process is famously intimate. She works with small crews, natural light when possible, and an ear finely tuned to the emotive force of music. Soundtracks are not an afterthought but an emotional architecture — Air, The Cure, Phoenix, Bow Wow Wow — each track becoming part of the character’s pulse.

Central to her work is a fascination with women in gilded cages. Whether teenage sisters in suburbia, a queen in Versailles, or Priscilla Presley in Graceland, Coppola returns again and again to women both elevated and suffocated by the worlds they inhabit.

Films in Focus

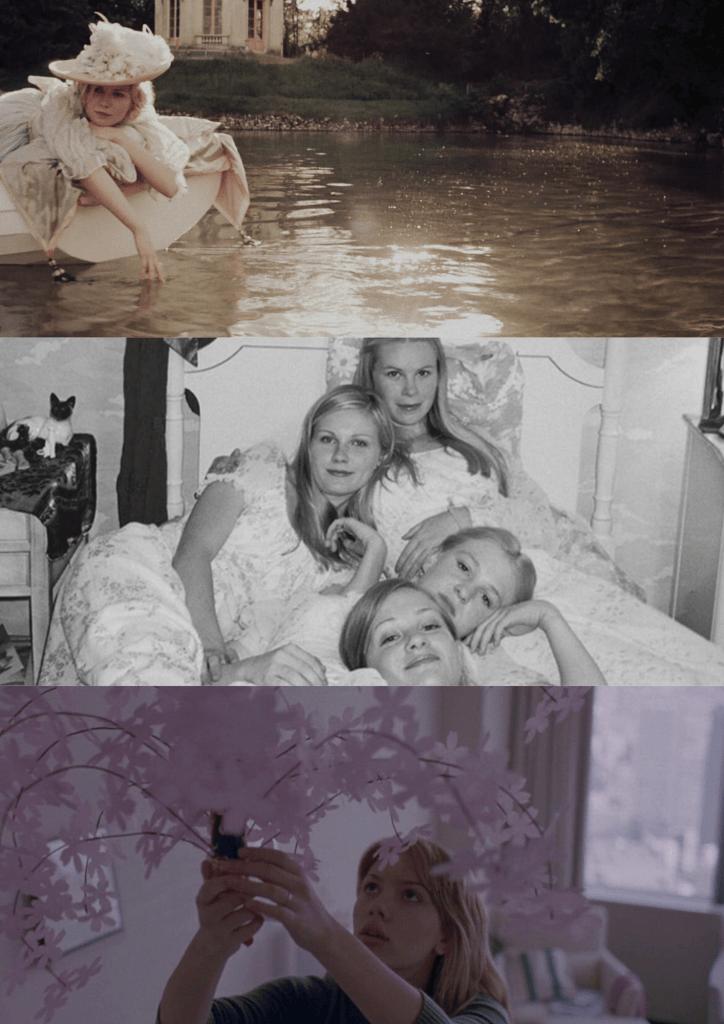

The Virgin Suicides (1999)

Adapted from Jeffrey Eugenides’ novel, Coppola’s debut is dreamlike and devastating. The Lisbon sisters, viewed through the nostalgic lens of neighborhood boys, become both flesh and myth. The film floats on soft focus, languorous pacing, and a bittersweet narration, marking Coppola as a director deeply attuned to memory and longing.

Lost in Translation (2003)

The film that defined her career. Scarlett Johansson and Bill Murray, adrift in Tokyo, find fleeting intimacy amid alienation. Coppola captures jet-lagged melancholy in neon light, shoegaze soundtrack, and whispered silences. Awarded the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay, it crystallized Coppola’s reputation as a poet of dislocation.

Marie Antoinette (2006)

Lavishly shot in Versailles, the film reimagines the queen not as a symbol of decadence but as a teenager trapped in rituals of power. Infused with pastel palettes, Manolo Blahnik shoes, and a soundtrack of New Order and The Strokes, Coppola’s audacious vision polarized critics but has since been re-evaluated as a landmark in feminist period cinema.

Somewhere (2010)

Minimalist to the point of meditation, Somewhere portrays a Hollywood star (Stephen Dorff) numbed by excess, reawakened by the presence of his daughter (Elle Fanning). Long takes of Ferraris circling endlessly or strippers repeating routines capture celebrity ennui with quiet precision.

The Bling Ring (2013)

Based on true events, this film follows LA teenagers who rob celebrity homes. It is at once glossy and ironic — a critique of consumer culture that never loses Coppola’s lush aesthetic.

The Beguiled (2017)

Set in a cloistered girls’ school during the American Civil War, the film explores desire, jealousy, and power when a wounded soldier intrudes. Coppola’s sharp framing and muted tones earned her Best Director at Cannes, making her only the second woman in history to win the prize.

On the Rocks (2020)

A light father-daughter caper through New York, starring Rashida Jones and Bill Murray. Playful, jazz-inflected, but still tinged with Coppola’s signature melancholy.

Priscilla (2023)

Based on Priscilla Presley’s memoir, Coppola revisits her central theme: a young woman defined and confined by fame and romance. It resonates as a spiritual companion to The Virgin Suicides and Marie Antoinette, closing a thematic circle spanning her career.

The Coppola Legacy

Over two decades, Sofia Coppola has carved out a cinema of whispers, daydreams, and unspoken yearnings. Where her father filled the screen with operatic grandeur, she has made stillness radical. In an industry that often equates power with noise, she insists on the quiet, the feminine, the intimate.

Her influence extends beyond film. Coppola’s aesthetic — pastel palettes, natural light, indie rock soundtracks — has become a visual language in fashion, photography, even social media mood boards. What was once dismissed as “soft” has proven enduring, shaping how a generation understands the look and feel of alienation.

Sofia Coppola’s films remind us that beauty and melancholy are not opposites but companions, and that cinema can be both gossamer-thin and indelibly strong.