Agnès Varda never looked like a revolutionary. Barely five feet tall, with her signature two-tone bowl haircut, she appeared more like a mischievous aunt than a cinematic radical. Yet across six decades, she transformed film, refusing categories, inventing new grammars of storytelling, and inspiring generations of directors. If Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut embodied the French New Wave’s swagger, Varda gave it soul.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Born in Brussels in 1928 to a Greek father and French mother, Varda grew up on the Mediterranean coast. She studied art history at the École du Louvre and photography at the École des Beaux-Arts, before working as a still photographer in Sète. This background shaped her eye: every frame she would later direct felt like a photograph in motion, a composition alive with texture, colour, and meaning.

She had no formal training in cinema when, at 26, she directed her first feature, La Pointe Courte (1955). Shot in a fishing village with a shoestring budget, it fused documentary realism with a fragmented narrative, anticipating the techniques that would soon define the Nouvelle Vague. Varda, in other words, invented the movement before it had a name.

Breaking Through: Cléo from 5 to 7

Her international breakthrough came with Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962), a haunting portrait of a Parisian singer awaiting the results of a medical test. The film follows Cléo in real time, across ninety minutes of Paris streets, cafés, and encounters. It is a meditation on mortality, femininity, and the gaze—shot with fluid camerawork and an acute sense of place.

Where her male contemporaries used women as muses or archetypes, Varda gave them interiority. Cléo is not an object but a subject, both fragile and strong, superficial and profound. With this film, Varda carved out a distinctly female voice within a movement often accused of misogyny.

Radical Experimentation

Throughout the 1960s and 70s, Varda refused to be pinned down. Le Bonheur (1965) juxtaposed idyllic imagery with unsettling themes of infidelity and conformity. One Sings, the Other Doesn’t (1977) became a feminist anthem, chronicling women’s liberation through song and friendship.

Her style shifted constantly—sometimes playful, sometimes austere, always exploratory. She blended documentary and fiction, collage and narrative, essay and portrait. To watch her films is to feel cinema being reinvented before your eyes.

Partnership with Jacques Demy

Varda married fellow director Jacques Demy, the maker of candy-coloured musicals like The Umbrellas of Cherbourg. Their artistic worlds could not have been more different—his stylised optimism versus her realism tinged with melancholy—but together they formed a partnership that nourished both. Varda later created poignant documentaries about Demy, including Jacquot de Nantes (1991), a tender reconstruction of his childhood made as he was dying of AIDS.

The Documentary Turn

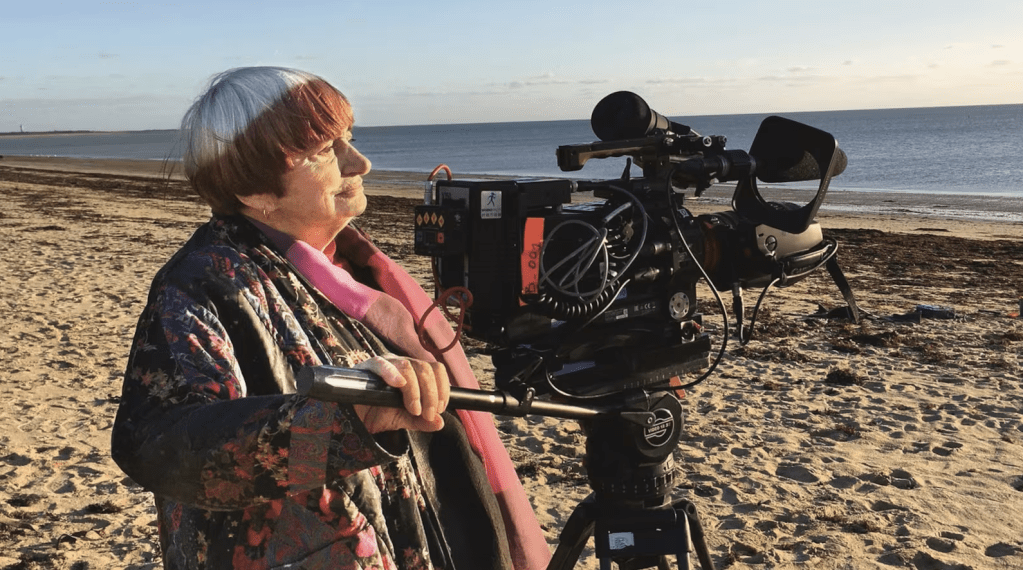

In the later decades of her career, Varda leaned increasingly toward documentary. The Gleaners and I (2000) is one of her most celebrated works, a digital video essay on people who collect society’s leftovers—farmers, artists, the poor—and a self-portrait of Varda herself as a gleaner of images and stories.

With Faces Places (2017), co-directed with the artist JR, she returned to the road, pasting giant portraits of everyday people on village walls. The film became a surprise international hit, earning her an Academy Award nomination at age 89. Onstage at the Oscars, she twirled in her sneakers and laughed: cinema’s grandmother still full of mischief.

Ten Essential Films by Agnès Varda

1. La Pointe Courte (1955)

Her debut, blending fiction and documentary. Ordinary villagers and a disintegrating couple share screen space, prefiguring the French New Wave.

2. Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962)

A ninety-minute real-time journey through Paris as a singer awaits her medical diagnosis. A study of femininity, mortality, and urban life.

3. Le Bonheur (1965)

A deceptively idyllic film, where radiant imagery conceals a meditation on infidelity, happiness, and the social roles of women.

4. Lions Love (… and Lies) (1969)

An experimental Los Angeles chronicle starring Warhol superstar Viva and the creators of Hair, blurring documentary and fiction in late-1960s counterculture.

5. Daguerreotypes (1976)

A documentary portrait of Varda’s own Parisian street, Rue Daguerre, capturing the intimacy of small shops and neighbourhood life.

6. One Sings, the Other Doesn’t (1977)

A feminist musical tracing two women across fifteen years of friendship, political awakening, and the fight for reproductive rights.

7. Vagabond (1985)

One of her darkest works: the story of a young drifter found dead in a ditch, told through flashbacks and interviews. A raw exploration of freedom and marginalisation.

8. Jacquot de Nantes (1991)

A tender film about Jacques Demy’s childhood, blending reconstruction with documentary footage, made as he was dying. Both tribute and farewell.

9. The Gleaners and I (2000)

A digital-era masterpiece. Varda films people who live from society’s cast-offs, while reflecting on her own life and aging. Radical, intimate, and humane.

10. Faces Places (2017)

Her late-life collaboration with artist JR, travelling through rural France to create large-scale portraits of ordinary people. A joyful meditation on memory and community.

Legacy

Varda died in 2019, but her influence continues to grow. She is celebrated as a pioneer of feminist filmmaking, a forerunner of the documentary essay, and a model of artistic freedom. Her career spanned celluloid and digital, feature and short, fiction and documentary—proving that categories are cages to be broken.

What made Varda singular was her refusal to separate life from art. She filmed her neighbours, her friends, her lovers, herself. She turned her own wrinkles into images, her garden into cinema, her grief into poetry. Her films do not simply depict reality—they live inside it, attentive to its textures and contradictions.

In an industry dominated by male auteurs, Varda carved out her own space, without bluster or manifesto, simply by making films her way. She remains proof that cinema can be both playful and profound, intimate and political, personal and universal.

Agnès Varda left us with a body of work as varied as life itself, and with a lesson: to look closely, to look tenderly, to keep looking.