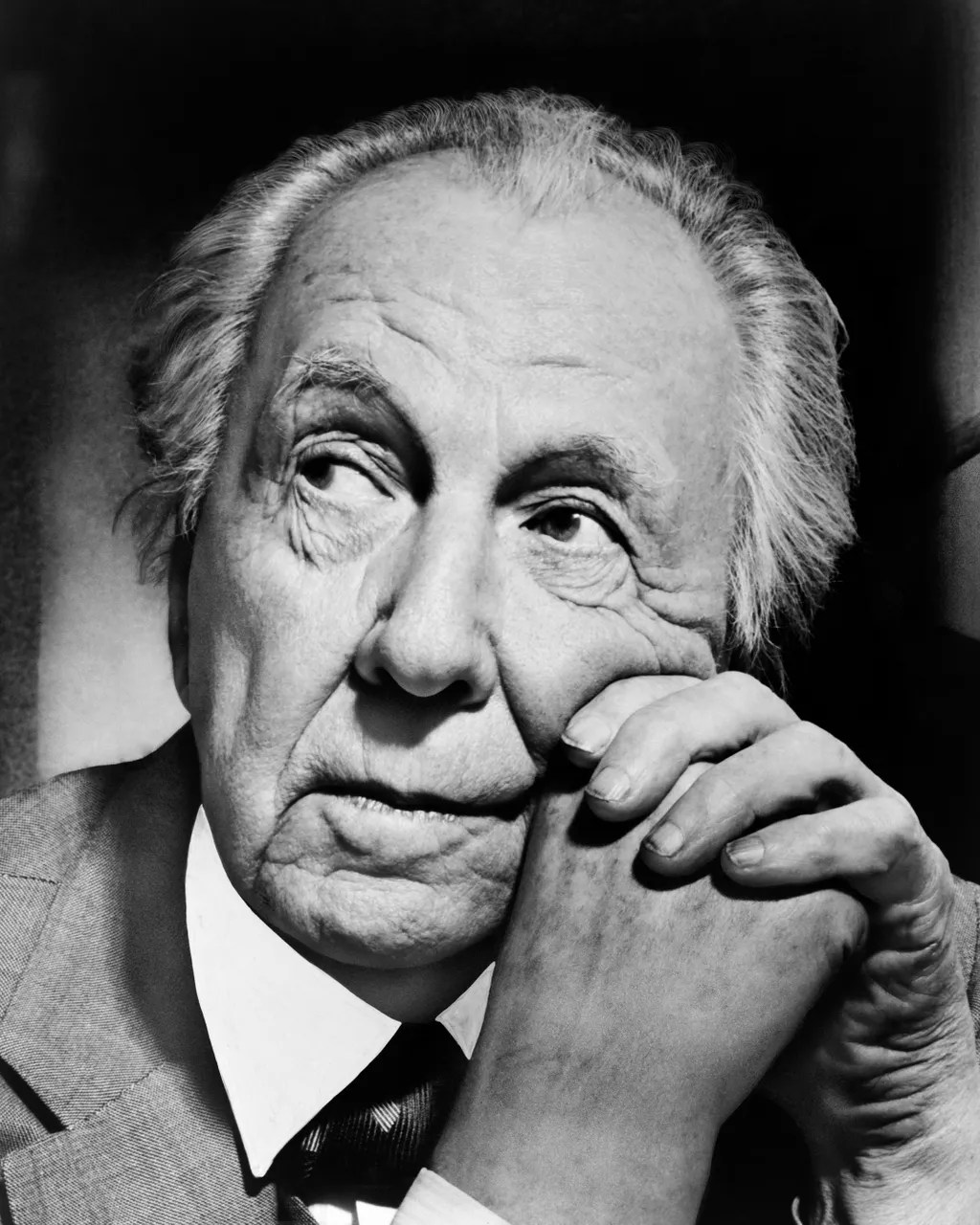

Few figures in modern history embody both genius and scandal quite like Frank Lloyd Wright. To his admirers, he was the visionary who made buildings breathe with their surroundings, inventing a new American architecture rooted in landscape and democracy. To his detractors, he was an egotist, a man of tempestuous loves and public ruin. To history, he is both: one of the most original creators of the twentieth century, and one of its most complicated men.

Prairie Prophet

Born in 1867 in rural Wisconsin, Wright came of age during America’s restless late nineteenth century, when the country was straining toward modernity. He apprenticed in Chicago under Louis Sullivan, “the father of skyscrapers,” who believed that form follows function. Wright adopted the lesson, then turned it inside out.

By the 1890s, he had developed his own Prairie School: long horizontal lines, low-pitched roofs, open floor plans, and ribbons of windows that blurred the line between inside and out. His Robie House in Chicago (1909) remains a manifesto in brick and glass: a domestic space that feels like a slice of landscape. In these early years, Wright offered an architecture that was distinctly American, wide as the plains, rejecting Old World ornament for something organic and new.

Scandal and Reinvention

Wright’s life was as turbulent as his architecture was serene. In 1909, at the height of his Prairie fame, he scandalized society by leaving his wife and six children for Mamah Borthwick Cheney, the wife of a client. They retreated to Taliesin, the house Wright built for them in Wisconsin, where he attempted to fashion an artistic utopia.

The idyll ended in horror. In 1914, a disgruntled servant set fire to Taliesin and murdered seven people with an axe, including Borthwick. The tragedy haunted Wright forever, but it did not extinguish his ambition. Instead, it became part of his myth: the wounded genius who rebuilt after devastation.

Fallingwater and the Sublime

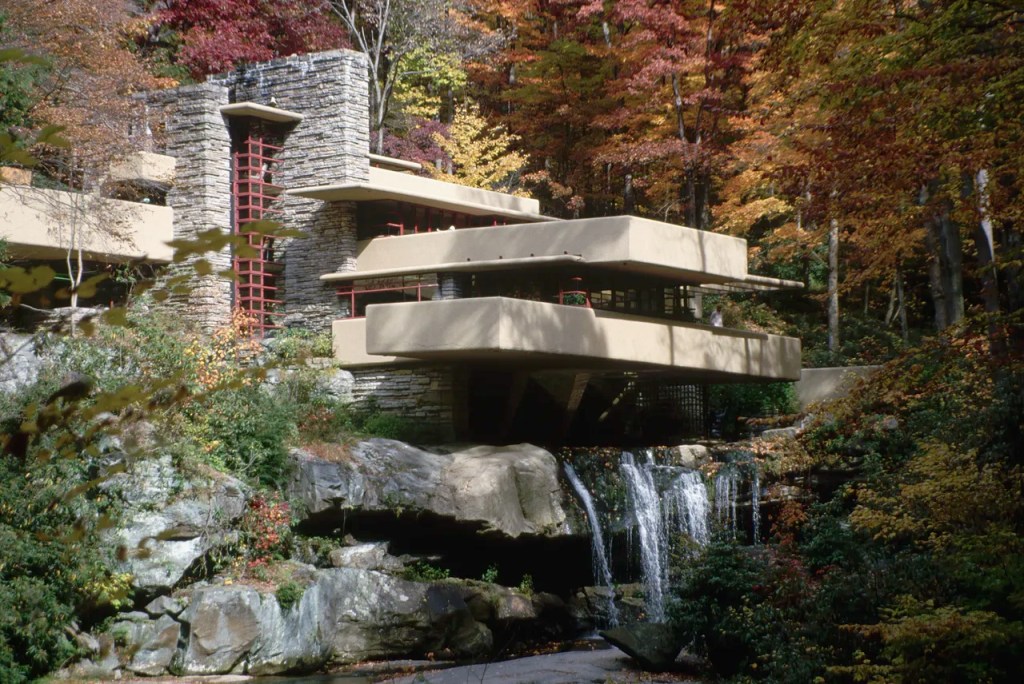

Wright’s career stretched nearly seventy years, punctuated by ruin and resurgence. His greatest revival came in the 1930s, during the Great Depression, when most architects were sidelined. At 67, he unveiled his masterpiece: Fallingwater (1935), a Pennsylvania house perched over a waterfall.

Commissioned by the Kaufmann family, Fallingwater is more than a residence—it is a symphony of stone and cantilevered concrete, hovering above rushing water. It remains one of the most celebrated houses in history, a structure so seamlessly integrated with nature that it feels inevitable, like it grew there. Time magazine put it on its cover in 1938, proclaiming Wright the greatest living architect.

Usonian Democracy

Wright never limited himself to the rich. He dreamed of transforming American life through design. His Usonian houses, built in the 1930s–50s, were intended as affordable models for the middle class: modest in scale, open in plan, constructed of natural materials, and designed to merge with the landscape.

Carports, radiant heating, and built-in furniture—all innovations now commonplace—emerged from his Usonian vision. To Wright, architecture was not just shelter but philosophy. A house should shape its inhabitants, teaching them to live with light, air, and flow.

The Guggenheim and the Last Statement

Even in his final years, Wright was unrelenting. At 92, he completed the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York (1959): a white spiral rising on Fifth Avenue like a modernist nautilus shell. Critics were divided—some called it a monstrosity, others a revelation—but it cemented Wright’s place not only as an architect of houses but as a creator of civic monuments.

The Contradictions of a Genius

Brilliant, arrogant, magnetic, irresponsible—Wright was a man of extremes. He cultivated apprentices at his Taliesin Fellowship, often as much a cult of personality as an architecture school. He courted clients with charm, then alienated them with delays and budget overruns. He declared himself the world’s greatest architect, and in the end, history largely agreed.

Legacy

More than 1,000 designs, 532 completed works, and an influence that spans continents: Wright’s fingerprints are on suburban homes, on corporate campuses, on every architect who has ever tried to dissolve the line between inside and outside. In 2019, eight of his buildings—including Fallingwater, the Robie House, and the Guggenheim—were inscribed as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

What makes Wright enduring is not just the drama of his life, but the clarity of his vision: that architecture must be organic, rooted in place, responsive to nature, and expressive of human spirit. He once wrote, “Study nature, love nature, stay close to nature. It will never fail you.” His greatest works embody that promise.

Frank Lloyd Wright remains the most American of architects: flawed, defiant, visionary. His life was a storm, but from that storm he built sanctuaries—spaces where nature and spirit converge. More than half a century after his death, we still live in his shadow, and in his light.