In the wreckage of World War I, amid the disillusionment of a generation, a radical new art movement was born: Dada. Emerging in Zürich in 1916, Dada rejected logic, tradition, and aesthetic convention in favor of absurdity, spontaneity, and provocation. Its practitioners — poets, painters, performers — sought not to create beauty but to explode it, not to console but to confront. For them, art was not a product but a weapon, an act of resistance against the structures that had led Europe into catastrophe.

The Birth at Cabaret Voltaire

The birthplace of Dada was Cabaret Voltaire, a bohemian nightclub in neutral Switzerland founded by Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings. Here, amid poetry readings, nonsensical chants, and anarchic performances, Dada declared itself. Tristan Tzara, Richard Huelsenbeck, Marcel Janco, and Hans Arp soon joined, staging evenings of cacophony and chance. Ball, in his cardboard “magical bishop” costume, reciting sound poems in invented languages, captured the spirit: art as anti-art.

A Name Without Meaning

Even its name mocked convention. Dada was said to have been plucked at random from a dictionary — French for “hobbyhorse,” German baby talk, or nothing at all. The refusal to fix meaning was the point: Dada was movement as gesture, as protest, as absurdity itself.

Paris, Berlin, New York

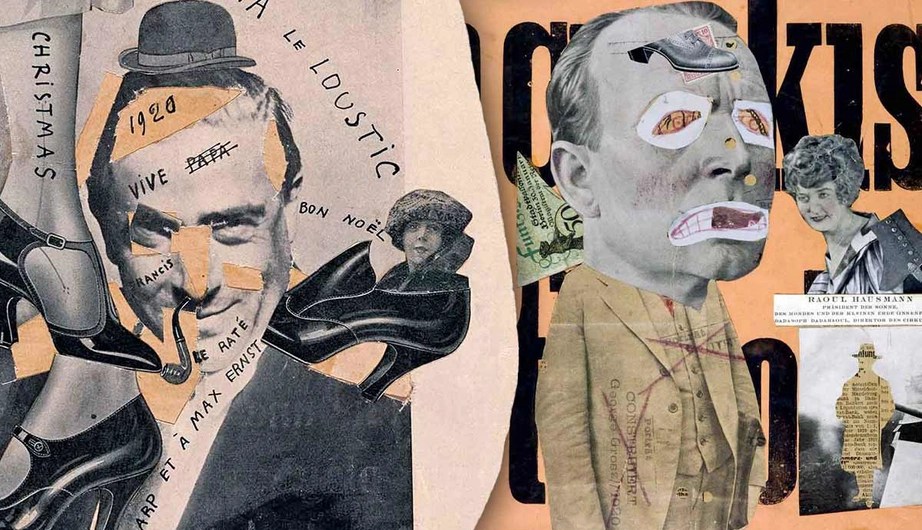

From Zürich, Dada spread like wildfire. In Berlin, George Grosz and John Heartfield turned satire into political weaponry, producing anti-militarist montages. In Paris, Tzara’s manifestos and soirées scandalized the cultural establishment. In New York, Marcel Duchamp redefined art with his readymades — a urinal titled Fountain, a bicycle wheel mounted on a stool — challenging the very idea of authorship. Man Ray, Francis Picabia, and others joined him, making Manhattan a transatlantic hub of irreverence.

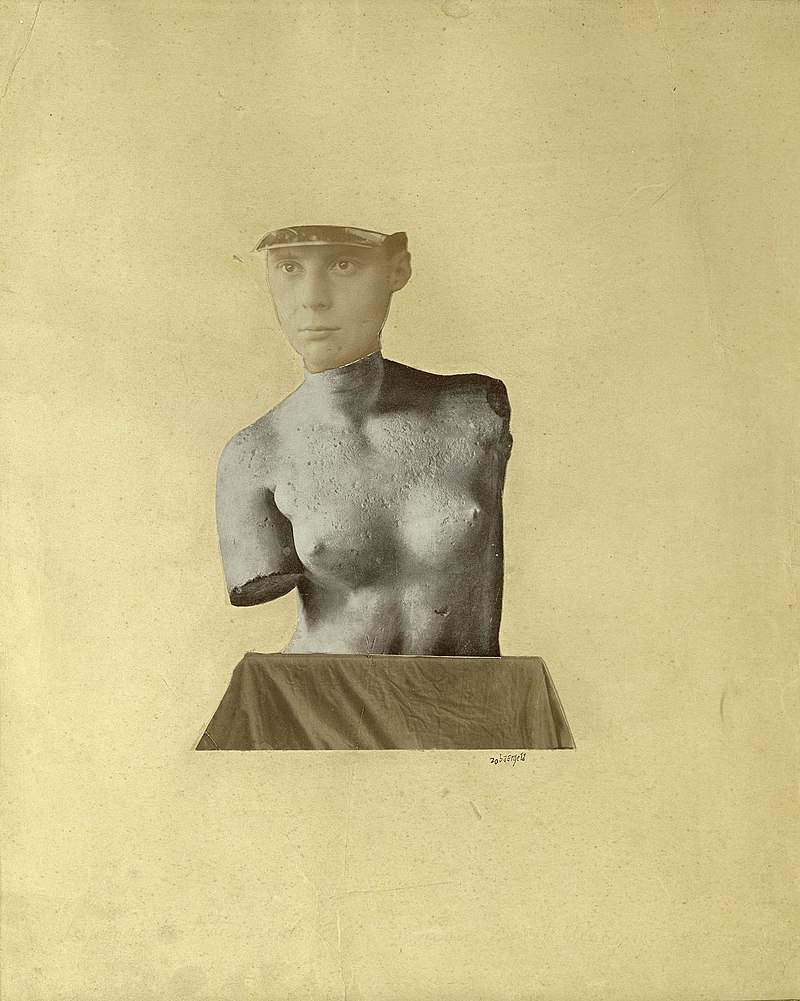

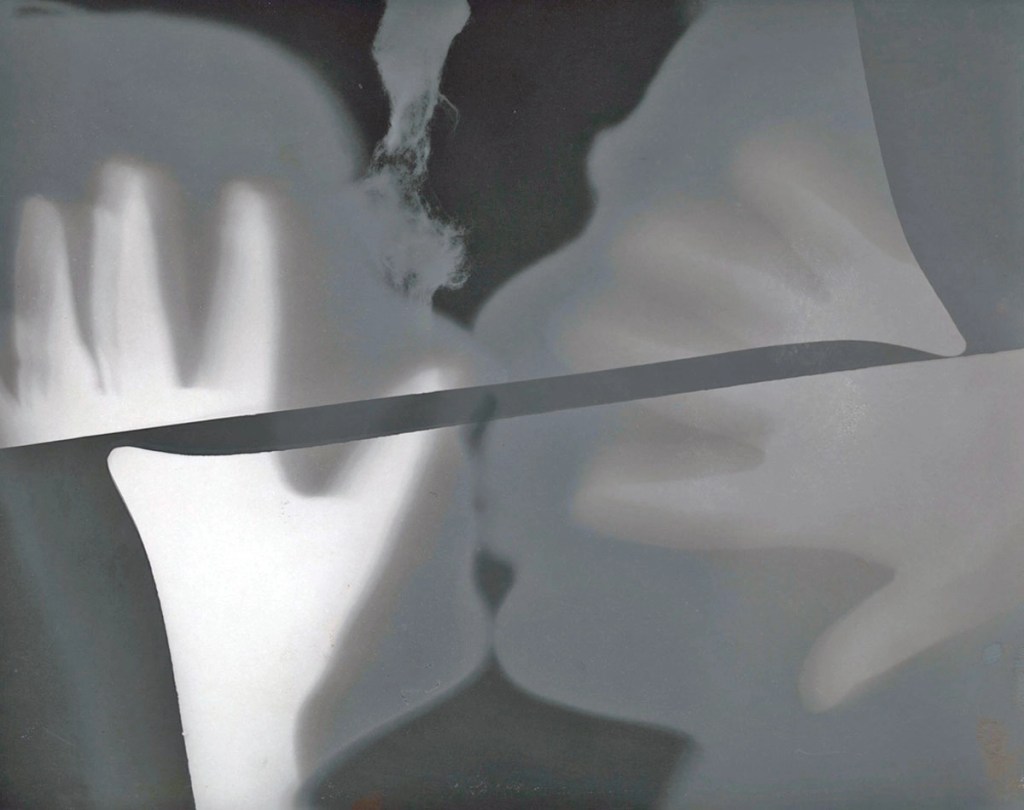

The Language of Collage and Chance

Dadaists invented new artistic languages. Collage and photomontage, pioneered by Hannah Höch, fragmented modern life into ironic juxtapositions. Chance became principle: Jean Arp dropped torn paper onto a sheet and affixed them where they fell, declaring the random arrangement truer than reasoned composition. Typography was disrupted, words scrambled, and performance turned into noise.

From Nihilism to Surrealism

For many, Dada seemed nihilistic: a refusal to build, only to destroy. But its negation cleared the ground for reinvention. By the early 1920s, many Dadaists had drifted into Surrealism, where unconscious desire replaced absurdity as guiding force. Yet Dada’s provocations — its collages, manifestos, performances — remain the most direct expression of postwar disillusionment.

The Legacy of Dada

Although the movement itself lasted barely a decade, its influence reverberates through modern art. Conceptual art, performance art, Pop Art, and postmodernism all trace roots to Dada’s irreverence. Duchamp’s Fountain remains one of the most debated works of the 20th century, its echo found in everything from Warhol’s soup cans to contemporary installations.

Dada’s genius was to insist that art could be anything — or nothing. In refusing order, it captured the chaos of its age. In rejecting meaning, it forced new forms of meaning into existence. In laughter and nonsense, it offered the most searing critique of a world gone mad.

Key Figures

- Hugo Ball & Emmy Hennings – Founders of Cabaret Voltaire; pioneers of sound poetry and performance.

- Tristan Tzara – Poet and polemicist, author of Dada’s manifestos.

- Marcel Duchamp – Master of the readymade, whose provocations redefined modern art.

- Hannah Höch – Innovator of photomontage, satirizing politics and gender.

- Jean Arp – Abstract collages created by chance, embracing randomness as principle.

Landmark Works

- Fountain (1917) – Marcel Duchamp’s urinal turned on its side, submitted to an exhibition and rejected, now iconic.

- Cut with the Kitchen Knife (1919–20) – Hannah Höch’s photomontage, dissecting Weimar politics and culture.

- Karawane (1916) – Hugo Ball’s sound poem, written in invented language and performed in Zurich.

- LHOOQ (1919) – Duchamp’s defaced Mona Lisa, moustached and irreverent.

- Collages by Jean Arp (1916–18) – Abstract compositions dictated by chance.

Where to See Dada

- Cabaret Voltaire, Zürich – The movement’s birthplace, now a museum and cultural space.

- Museum of Modern Art, New York – Holds major works by Duchamp, Höch, and Arp.

- Centre Pompidou, Paris – A vast collection of Dada and Surrealist works.

- Berlinische Galerie, Berlin – Specialises in Berlin Dada, photomontage, and political satire.

TL;DR

Dada was not an art movement but an anti-art movement: born in wartime chaos, fueled by absurdity, defined by refusal. From Hugo Ball’s sound poems to Duchamp’s Fountain, it dismantled meaning in order to expose madness. Its spirit of provocation endures wherever art challenges, mocks, and refuses to conform.