Perched on the cliffs of Capri’s Punta Massullo, its red walls blazing against the Tyrrhenian Sea, Villa Malaparte is one of the most arresting houses of the 20th century. At once austere and theatrical, it is both architectural landmark and cinematic icon, immortalised in Jean-Luc Godard’s Contempt (1963). Few houses better embody the interplay of architecture, literature, and myth.

A Writer’s Vision

The villa was commissioned in the late 1930s by Italian writer and provocateur Curzio Malaparte (1898–1957). Initially designed by architect Adalberto Libera, the house quickly became Malaparte’s own project. He rejected Libera’s more orthodox modernist plans, insisting on a design that reflected his idiosyncratic vision: rigorous, monumental, yet deeply personal.

The House as Sculpture

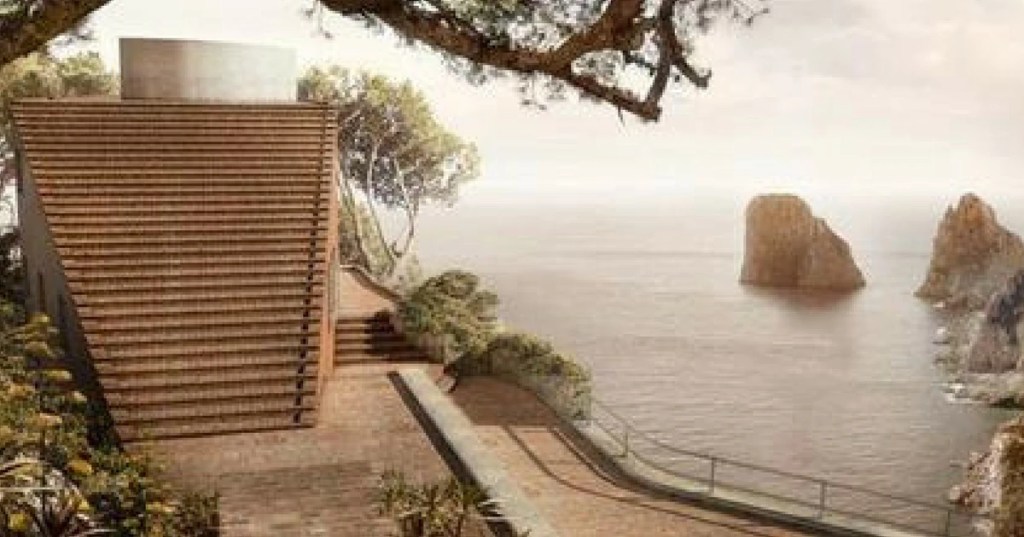

Completed in 1942, Villa Malaparte is an object carved into the rock of Capri itself. Its form is deceptively simple: a red masonry box set upon a natural promontory, with a trapezoidal outdoor staircase rising to a vast rooftop terrace. Here, architecture and landscape merge. The staircase leads not to a structure, but to the sky and the sea — a surrealist gesture, both functional and symbolic.

Inside, the villa is restrained yet dramatic: whitewashed walls, tiled floors, and expansive windows framing panoramic views of the sea and Faraglioni rocks. The interiors eschew ornament, relying instead on proportion and vista for their poetry.

Cinema and Contempt

Villa Malaparte might have remained an architectural curiosity were it not for Jean-Luc Godard. In Contempt, the villa becomes more than setting; it becomes character. Brigitte Bardot and Michel Piccoli wander through its stark rooms, their failing marriage mirrored in the villa’s solitude and geometry. On the rooftop terrace, Bardot lies sunbathing as the sea stretches endlessly beyond — an image that turned the villa into one of cinema’s most unforgettable spaces.

Myth and Legacy

After Malaparte’s death, the villa fell into disrepair, inaccessible and mysterious. Restored in the 1980s by architect Paolo Vitti and the Malaparte Foundation, it remains private, rarely open to visitors. Its inaccessibility has only deepened its aura of myth. For architects, it stands as a masterwork of Italian Rationalism infused with personal eccentricity. For cinephiles, it is forever entwined with Godard’s fractured, beautiful meditation on art and desire.

A House at the Edge

Villa Malaparte endures as a paradox: modernist yet archaic, minimalist yet theatrical, private yet iconic. To see it — even from a boat passing below Capri’s cliffs — is to glimpse an architecture that aspires not merely to shelter, but to symbol. It is less a house than a manifesto carved into stone: of solitude, of vision, of human ambition at the edge of the sea.

Lifestyle Notes

Film & Culture

- Contempt (Le Mépris), 1963 – Jean-Luc Godard’s film that enshrined the villa in cinematic history.

- Criterion Collection – Restored edition of Contempt.

Architecture

- Adalberto Libera – Italian Rationalist architect originally credited, though Malaparte himself re-shaped the villa.

- Malaparte Foundation – Custodians of the villa and its legacy.

Visiting Capri

While Villa Malaparte itself remains closed to the public, visitors to Capri can see it from the sea on boat tours.

- Capri Boat Service – Offers excursions with views of Punta Massullo.

- Capri Tourism – Official site with guides to the island.

TL;DR

Villa Malaparte is not simply a house but a symbol: of a writer’s ego, of modernism’s dialogue with landscape, of cinema’s power to mythologise architecture. Painted red against the blue sea, it remains one of the most enigmatic and iconic villas in the world — a sculptural dream poised on the cliffs of Capri.