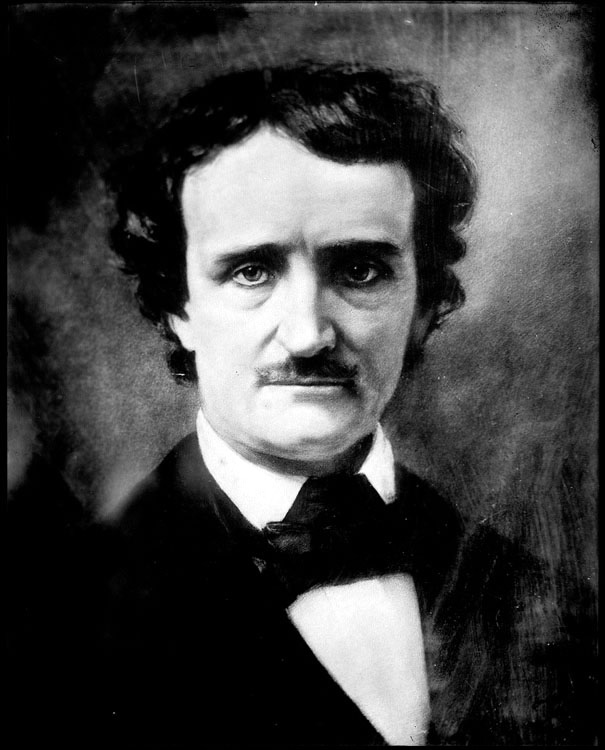

Edgar Allan Poe (1809–1849) remains one of the most singular figures in American letters: poet, critic, short story pioneer, and gothic visionary. His life, brief and tumultuous, has long been folded into the myth of his work — the impoverished genius, the tragic outsider, the writer of haunted tales who himself died mysteriously. But Poe’s legacy extends far beyond atmosphere and morbidity. He was an architect: of the modern short story, of detective fiction, of poetic rhythm and sound. To revisit Poe is to see not just the shadows of the gothic but the very foundations of American and European modernism.

A Life in Fragments

Born in Boston to itinerant actors and orphaned before the age of three, Poe was raised in Richmond, Virginia, by the Allan family, though never formally adopted. His life unfolded in precarious fragments: interrupted studies, quarrels with patrons, unstable editorial posts, chronic debt. He married his cousin Virginia Clemm when she was just thirteen, and her death in 1847 left him desolate. When Poe himself died two years later in Baltimore — delirious, wearing another man’s clothes, under circumstances never explained — the mystery of his life became inseparable from the mysteries of his art.

Invention of the Short Story

Poe’s greatest theoretical contribution was his insistence that a short story should aim at a “single effect.” Every word, every image, must serve the creation of a unified mood. This principle, articulated in his criticism and embodied in his fiction, anticipates both modernist concision and the strict mechanics of genre writing. His tales are not loose collections of events but carefully designed machines of atmosphere, each calibrated to deliver dread, beauty, or revelation.

Poetry of Sound and Mourning

Though often overshadowed by his tales, Poe’s poetry shaped his reputation in his lifetime. The Raven (1845) transformed him into a celebrity, its refrain of “Nevermore” echoing across parlours and lecture halls. But his poems, from Annabel Lee to Ulalume, are less about gothic décor than about sound: incantatory rhythms, refrains, and repetitions that anticipate Baudelaire, Mallarmé, and the Symbolist movement. Love and loss are refracted into music — grief made lyrical.

The Father of Detective Fiction

In The Murders in the Rue Morgue (1841), Poe created C. Auguste Dupin, the eccentric detective who solves crimes through analytical deduction. Dupin prefigured Sherlock Holmes, Hercule Poirot, and countless fictional investigators. It is no exaggeration to call Poe the father of the detective story, a genre that would become one of the most enduring in modern literature.

Ten Essential Works

- The Raven (1845)

A study in rhythm and refrain, transforming grief into incantation. Its dark bird and repeated “Nevermore” made Poe an international sensation and cemented his place as America’s most famous poet. - The Fall of the House of Usher (1839)

A gothic allegory where architecture mirrors psychology. The decaying mansion becomes both setting and symbol for hereditary decline and madness. - The Tell-Tale Heart (1843)

A masterpiece of unreliable narration. A murderer insists on his sanity while describing a crime born of obsession, paranoia, and guilt. - Annabel Lee (1849)

Poe’s final poem, a haunting meditation on eternal love and death. Its folkloric simplicity masks its cosmic scale. - The Murders in the Rue Morgue (1841)

The birth of detective fiction. Dupin’s analytical method established the genre’s enduring conventions. - The Cask of Amontillado (1846)

A tale of revenge in Venetian catacombs. Its economy of style and chilling cruelty remain unmatched. - The Black Cat (1843)

A dark twin to The Tell-Tale Heart, charting alcoholism, cruelty, and supernatural retribution. - Eureka (1848)

A speculative prose-poem theorizing the origins of the universe. Scientifically flawed but imaginatively daring, it reveals Poe’s metaphysical ambition. - Ligeia (1838)

A tale of resurrection and obsession. Suggests the will’s power to transcend death, blending gothic romance with metaphysics. - The Philosophy of Composition (1846)

Poe’s critical essay outlining how he constructed “The Raven.” Whether fact or performance, it shaped debates on authorship and intention for generations.

Death and Afterlife

Poe’s mysterious end only magnified his legend. Found delirious in Baltimore and dead days later at forty, his passing became an extension of his art: unresolved, uncanny, open to interpretation. In France, Baudelaire and Mallarmé translated and celebrated him, elevating Poe as a prophet of modernity. In America, he became a paradox — a Southern outsider whose innovations defined national literature, a critic of discipline who lived chaotically, a poet of grief who became a pop-culture icon.

An Enduring Influence

Poe’s reach stretches far. He shaped the gothic tradition, invented the detective genre, and infused poetry with soundscapes that reverberated through European Symbolism and American modernism alike. His obsessions — with death, memory, and the uncanny — remain universal. Writers from Dostoevsky to Borges, filmmakers from Roger Corman to Tim Burton, and musicians from Debussy to Lou Reed have found in Poe a mirror for their own creativity.

TL;DR

Edgar Allan Poe was not merely a teller of horror stories but an architect of form and feeling. His tales and poems built new genres, his criticism demanded rigor, and his obsessions with beauty and terror reshaped literature on both sides of the Atlantic. He remains America’s great gothic innovator — a writer whose shadows illuminate the very structure of modern storytelling.