Few directors have reshaped the possibilities of film as radically and enduringly as Stanley Kubrick. Working across genres but loyal to none, Kubrick forged a cinematic language defined by precision, ambiguity, and a relentless fascination with human psychology. His films are not simply watched; they are inhabited — vast, meticulously composed worlds where narrative, imagery, and sound cohere into something more like architecture than entertainment.

Born in New York in 1928, Kubrick began as a photographer for Look magazine, and that early training is everywhere in his work: the geometric rigor, the sculptural use of light, the instinct for visual metaphor. But cinema allowed him to pair this visual discipline with an intellectual ferocity. He was not a director of spontaneity or warm improvisation; he was an engineer of cinematic experience, endlessly revising, controlling, refining. What he sought was not realism but truth — the deeper psychological truths that slip beneath the surface of plot.

An Artist of the Human Condition

Kubrick’s films repeatedly examine power, violence, institutional systems, and the fragile machinery of the human mind. In Paths of Glory, he exposes the cruelty of military hierarchy; in Dr. Strangelove, he treats the absurdity of nuclear annihilation with lethal satire. A Clockwork Orange probes free will, youth culture, and authoritarian correction. The Shining is a tour de force of psychological horror, where isolation metastasises into madness. And Eyes Wide Shut — his final, eerily intimate film — returns to his lifelong concern: the private fantasies and subterranean desires that shape identity and dismantle illusions.

What binds these disparate films together is Kubrick’s uncanny ability to create a mood — a precise psychic temperature. He does this through the harmony of image and sound: disquieting wide angles, slow tracking shots, symmetrical compositions, classical music weaponised into dread. A Kubrick film feels cold to the touch, but burns over time.

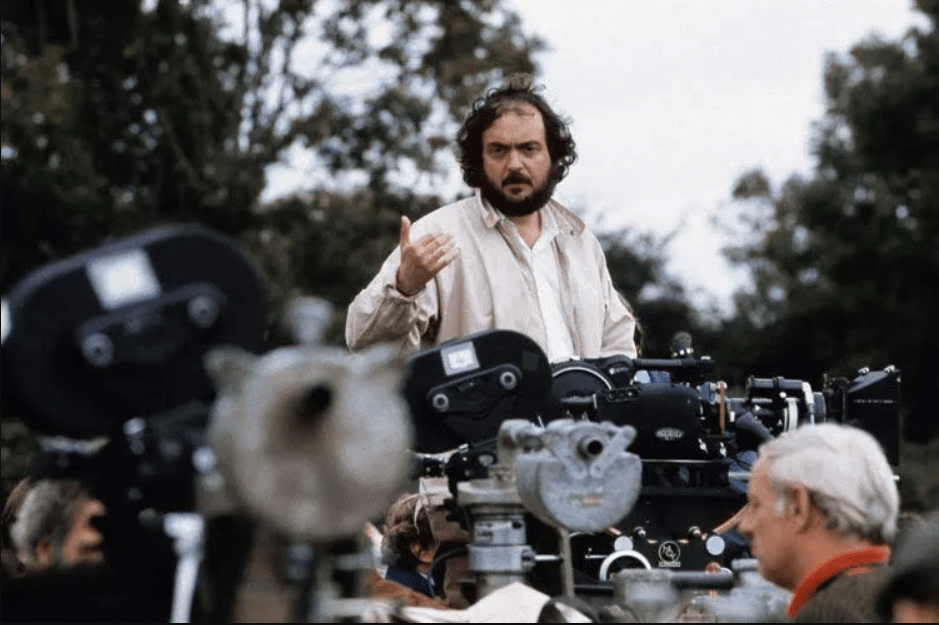

A Perfectionist and a Myth

The mythology around Kubrick is as strong as the work itself. Stories of obsessively repeated takes, sealed-off sets, strict control over actors — all true, and all part of his pursuit of a cinema that refuses compromise. And yet, the result is never sterile. His films teem with life: sensuality (Eyes Wide Shut), terror (The Shining), melancholy (Barry Lyndon), and the cosmic sublime (2001: A Space Odyssey).

Kubrick remains, decades after his death, the director most invoked as a benchmark — the one whose influence haunts everything from contemporary prestige television to music videos to video games. He was not prolific, but he was monumental.

Stanley Kubrick’s Films Ranked

- 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) — The pinnacle; cinema reimagined as philosophy, myth and pure image.

- Barry Lyndon (1975) — A painterly masterpiece; the most beautiful film ever shot.

- The Shining (1980) — A labyrinth of dread; endlessly reinterpreted, permanently unsettling.

- Dr. Strangelove (1964) — Nuclear madness rendered with lethal wit.

- Paths of Glory (1957) — A devastating anti-war humanist cry.

- Eyes Wide Shut (1999) — A dreamlike excavation of intimacy, desire, and illusion.

- A Clockwork Orange (1971) — Dystopian satire that still shocks.

- Full Metal Jacket (1987) — Brutal and bifurcated; a study of dehumanisation.

- The Killing (1956) — A tight, stylish noir; Kubrick finding his voice.

- Lolita (1962) — Uneven but hypnotic, with a career-defining performance from Peter Sellers.

- Killer’s Kiss (1955) — Early, slight, but visually striking.

- Fear and Desire (1953) — Kubrick’s disowned debut; interesting only as an origin point.