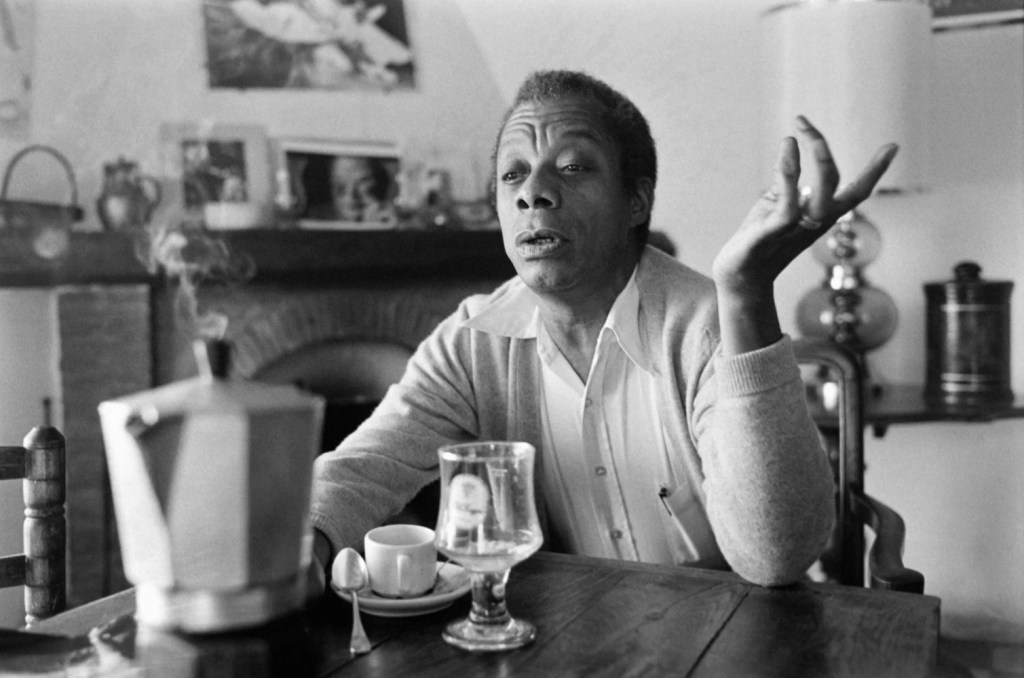

James Baldwin was one of the 20th century’s most essential writers, a man whose voice carried the urgency of politics, the intimacy of confession, and the beauty of poetry. He was novelist, essayist, playwright, and activist, but above all, he was a witness: to America’s racial history, to the lives of the dispossessed, and to the complexity of love and desire. His legacy endures because he wrote not only about his own time, but about the unfinished struggles that still define ours.

Beginnings in Harlem

Born in 1924 in Harlem, Baldwin grew up amid poverty, church life, and the turbulence of a segregated America. His early years were marked by both discipline and constraint — the pulpit offered him a voice, but also a narrowness he would eventually resist. By his late teens he had left the church, but not the cadences of sermon and scripture; those rhythms would shape his prose for life.

A scholarship took him to DeWitt Clinton High School, where he edited the literary magazine alongside classmates Richard Avedon and Emile Capouya. By the 1940s, Baldwin was determined to be a writer, even as racism and homophobia threatened to suffocate him in America. He left for Paris in 1948, beginning his life as an expatriate — a distance that gave him clarity to write about home.

Novels of Identity and Desire

Baldwin’s novels charted the intersections of race, sexuality, and belonging. Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953) drew from his Harlem childhood, transforming autobiography into spiritual inquiry. Giovanni’s Room (1956), set in Paris, was radical in its frank portrayal of same-sex desire, written decades before such themes gained mainstream acceptance.

His fiction was never simply about individuals; it was about individuals in history. Each character carried the weight of structures — religion, racism, family, nation — yet Baldwin rendered them with profound empathy. He understood people as flawed, yearning, resilient.

The Essay as Art and Weapon

If Baldwin’s novels revealed his gifts as a storyteller, his essays revealed him as a prophet. Collections such as Notes of a Native Son (1955), The Fire Next Time (1963), and No Name in the Street (1972) captured the raw contradictions of America: its ideals and its betrayals, its violence and its promises.

His essays are both literature and testimony. With piercing clarity, Baldwin described what it meant to live as a Black man in America, to navigate the intersections of race and sexuality, and to bear witness to injustice while refusing despair. His words became touchstones for the Civil Rights Movement, and his public debates — especially with figures like William F. Buckley at Cambridge in 1965 — remain electrifying documents of moral courage.

Style and Substance

Baldwin’s style was unmistakable. It combined the rhythms of the pulpit, the precision of French literary training, and the urgency of political witness. His prose could turn from lyrical to furious in a breath, capturing both the intimacy of personal confession and the grandeur of collective history.

He was never content to separate the personal from the political. To love, to suffer, to desire — these were political acts, because they revealed the truths society sought to suppress. In this, Baldwin was both writer and moral compass.

Later Years and Enduring Influence

Baldwin spent much of his life abroad, in France, Switzerland, and Turkey, but America remained his central subject. In later works like If Beale Street Could Talk (1974) and Just Above My Head (1979), he continued to explore love, family, and injustice with his characteristic depth.

He died in 1987 in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, France, leaving behind an oeuvre that remains as alive as when he wrote it. In recent years, Baldwin’s legacy has been re-energized by films like I Am Not Your Negro (2016), which brought his words to a new generation, and by the enduring resonance of his insights in the age of Black Lives Matter.

Baldwin Capsule: A Reading Guide

- Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953)

Baldwin’s debut novel, rooted in his Harlem youth. A lyrical exploration of faith, family, and identity, it remains one of the great American coming-of-age stories. - Giovanni’s Room (1956)

A groundbreaking novel of same-sex love, exile, and desire. Its Parisian setting and emotional candor made it revolutionary for its time — and still quietly radical today. - Another Country (1962)

A sprawling novel of love, race, and bohemian New York. Raw, experimental, and deeply human, it captures the turbulence of a changing America. - The Fire Next Time (1963)

Two searing essays — one a letter to his nephew, the other an analysis of America’s racial divide. Among Baldwin’s most prophetic and enduring works. - If Beale Street Could Talk (1974)

A tender love story shadowed by injustice, later adapted into Barry Jenkins’s luminous 2018 film. Both intimate and political, it is Baldwin at his most compassionate. - Collected Essays (Library of America, 1998)

The definitive anthology of Baldwin’s nonfiction, from Notes of a Native Son to No Name in the Street. Essential reading for his voice in full.

Baldwin on Screen and Stage

- The Fire Next Time (1963) – Inspired countless speeches and artistic works with its prophetic urgency.

- I Am Not Your Negro (2016) – Raoul Peck’s documentary, drawn from Baldwin’s unfinished Remember This House, brought his words vividly to life for new generations.

- If Beale Street Could Talk (2018) – Barry Jenkins’s adaptation reaffirmed Baldwin’s relevance, marrying his prose with luminous cinema.

- Plays – Works such as Blues for Mister Charlie (1964) extended Baldwin’s themes of justice and grief to the stage, fusing art with activism.

TL;DR

James Baldwin’s legacy is not confined to literature; it is inscribed in the conscience of a nation. He wrote with clarity, compassion, and fire, insisting that America reckon with its history even as he refused to let despair win. His words remain both mirror and map: reflecting the pain of injustice, but also charting the possibility of love and liberation.

To read Baldwin today is to encounter not only a writer of genius but a witness whose testimony is still unfinished. His voice continues to remind us that literature, at its highest, is not an escape from reality but an act of engagement — and a call to transformation.