He was called “the Emperor” on set: exacting, visionary, unstoppable. Akira Kurosawa not only reshaped Japanese cinema but redefined what world cinema could be. From rain-drenched battlefields to fog-shrouded castles, his films remain among the greatest dreams ever projected.

The Emperor of Cinema

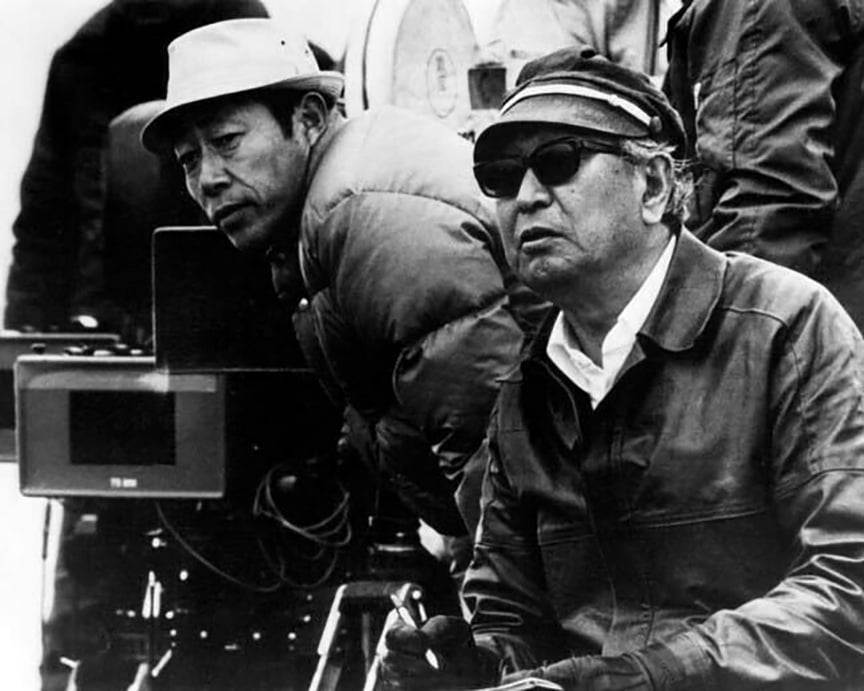

When Akira Kurosawa strode onto a set, he cut an unmistakable figure: cap pulled low, dark glasses in place, moving with the authority of someone who saw further than anyone around him. Crew members called him “the Emperor.” It wasn’t hyperbole. Kurosawa didn’t direct films so much as marshal them, orchestrating wind and weather, armies of extras, and actors whose faces he studied like landscapes. His sets were not democratic. They were kingdoms, with Kurosawa at the center, building worlds from scratch.

Born in Tokyo in 1910, Kurosawa lived through seismic upheavals—Japan’s militarization, the devastation of war, the trauma of occupation, and the rebirth of a modern nation. His films reflect this history, yet they rarely feel bound to one time or place. He borrowed from Shakespeare, Dostoevsky, and John Ford as easily as from samurai legend. What emerged was a cinema at once Japanese and global, timeless and urgent.

The Method of an Emperor

Kurosawa was a perfectionist. He painted full watercolors of every scene before shooting—his storyboards are works of art in themselves, saturated with the colors he demanded on screen. He used multiple cameras for action sequences, ensuring he could capture spontaneity from every angle. If he needed rain, he built machines that poured thousands of gallons of water until it lashed the earth like a monsoon. If he wanted authenticity, he ordered real armor for extras rather than studio costumes, heavy enough to exhaust the actors and give battle scenes their weary realism.

On Seven Samurai (1954), he rehearsed for months, assigning each of the villagers a detailed backstory—even if they never spoke on screen. On Ran (1985), his Shakespearean epic of betrayal, he directed vast battles with color-coded banners: yellow, red, and blue armies swirling across landscapes like living brushstrokes. He worked with the eye of a painter and the will of an architect, building worlds as much as filming them.

His Players

If Kurosawa was the Emperor, his court was filled with recurring collaborators who became his cinematic family. None more legendary than Toshiro Mifune, whose raw magnetism defined Kurosawa’s mid-century masterpieces. From the feral bandit in Rashomon (1950) to the wily ronin in Yojimbo (1961), Mifune gave Kurosawa’s moral dramas their unruly energy. “Mifune had a kind of animal intensity,” Kurosawa once said. “He was like a finely tuned engine.”

But equally crucial was Takashi Shimura, the quiet counterweight to Mifune’s tempest. In Ikiru (1952), Shimura gave one of cinema’s most humane performances as a bureaucrat who, facing death, rediscovers life. If Mifune was Kurosawa’s fire, Shimura was his soul.

Behind the camera, Kurosawa relied on cinematographer Asakazu Nakai, whose compositions gave depth and dynamism to sweeping landscapes and intimate interiors alike, and composer Fumio Hayasaka, who infused his films with scores that blended Japanese instrumentation and Western symphonic drama. Kurosawa’s cinema was collaborative, but his vision governed every detail.

East and West

Kurosawa often insisted he was both a Japanese and a Western artist. His heroes, though rooted in Japanese history, carried the universal burden of moral choice. The wandering ronin of Yojimbo became Clint Eastwood’s “Man with No Name” in Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars (1964). Seven Samurai was refashioned as The Magnificent Seven (1960), an American Western. George Lucas admitted that The Hidden Fortress (1958)—with its peasants providing a comic point of view, a disguised princess, and a mythic hero’s journey—inspired Star Wars.

Kurosawa’s cinematic language—his wipes and pans, his use of weather, his ability to stage chaos in perfect clarity—became part of the DNA of global filmmaking. His stories were local; their influence was planetary.

Collapse and Resurrection

Even emperors fall. In the 1970s, Japanese studios turned away from Kurosawa. His films were deemed too costly, too ponderous, too out of step with younger audiences. When Dodes’ka-den (1970), his first color film, flopped disastrously, he spiraled into despair, attempting suicide in 1971. For a moment, the greatest filmmaker of his generation seemed finished.

But his admirers abroad refused to let him vanish. George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola, flush with their own Hollywood success, lobbied for international financing. With their backing, Kurosawa returned with Kagemusha (1980), a tale of a thief impersonating a fallen warlord, which won the Palme d’Or at Cannes. Five years later came Ran, his late-career masterpiece, an apocalyptic reimagining of King Lear. With its vast battle scenes and indelible color, it was less a comeback than a coronation: proof that Kurosawa, even in decline, worked on a scale no one else could match.

The Cultural Afterlife

Kurosawa died in 1998, but his images remain alive everywhere. His influence stretches beyond cinema into television, anime, and video games: the duels of Ghost of Tsushima (2020) are framed with reverence for Kurosawa’s samurai choreography; Quentin Tarantino’s fractured narratives owe much to Rashomon. Even the weather in film—the use of rain, wind, fog as emotional agents—still carries his fingerprints.

What endures is not just the spectacle, but the moral seriousness. Kurosawa’s films insist that individuals, however powerless, must act with honor in a chaotic world. Whether a bureaucrat in Ikiru building a playground before he dies, or samurai sacrificing themselves for villagers in Seven Samurai, the question is always the same: what does it mean to live with dignity when dignity seems impossible?

The Emperor’s Dream

In his memoir, Kurosawa reflected: “Man is a genius when he is dreaming.” His films remain some of the greatest dreams ever projected, luminous and unsettling, filled with both terror and grace. They remind us that cinema, at its height, is not entertainment but vision—an attempt to stare into the storm of history and find beauty in its chaos.

For Kurosawa, film was not craft, not commerce, but necessity. He once said: “The artist’s role is to not look away.” And he never did.