Hollywood has always been fascinated by women who refuse to soften themselves for the screen. Few embodied that refusal more fully than Faye Dunaway. From the late 1960s onward, she appeared not as a “new kind” of actress but as something rarer: a classical star with a modern nervous system, a presence equal parts glamour and fracture.

Where her contemporaries offered accessibility—Jane Fonda’s activism, Diane Keaton’s comic warmth, Ellen Burstyn’s maternal gravitas, Barbra Streisand’s exuberant self-invention—Dunaway offered distance. She didn’t charm; she compelled. She carried herself, as one critic observed, “like a woman who had already survived the movie.”

Dunaway herself understood this quality. In her memoir Looking for Gatsby (1995), she wrote: “I was never the girl next door. I was always the girl across the hall, the one you couldn’t quite reach.” It is a strikingly apt self-portrait: close enough to be seen, but elusive, magnetic precisely because she withheld.

The 2022 documentary Faye tried to reconcile the contradictions: the stories of “difficult” behavior, the perfectionism, the string of performances that range from immortal to infamous. What emerged was the portrait of an artist who refused to treat acting as anything less than total commitment. As she once put it: “I don’t think you can do it halfway. You have to risk everything, or it shows.”

Her filmography reflects that creed. At her best, she delivered performances that reshaped American cinema. At her worst, she created moments so excessive that they became unforgettable anyway. Stardom, in Dunaway’s hands, was not about consistency but about magnitude.

Here, ten films that chart her artistry—and the unforgiving gaze she never allowed to waver.

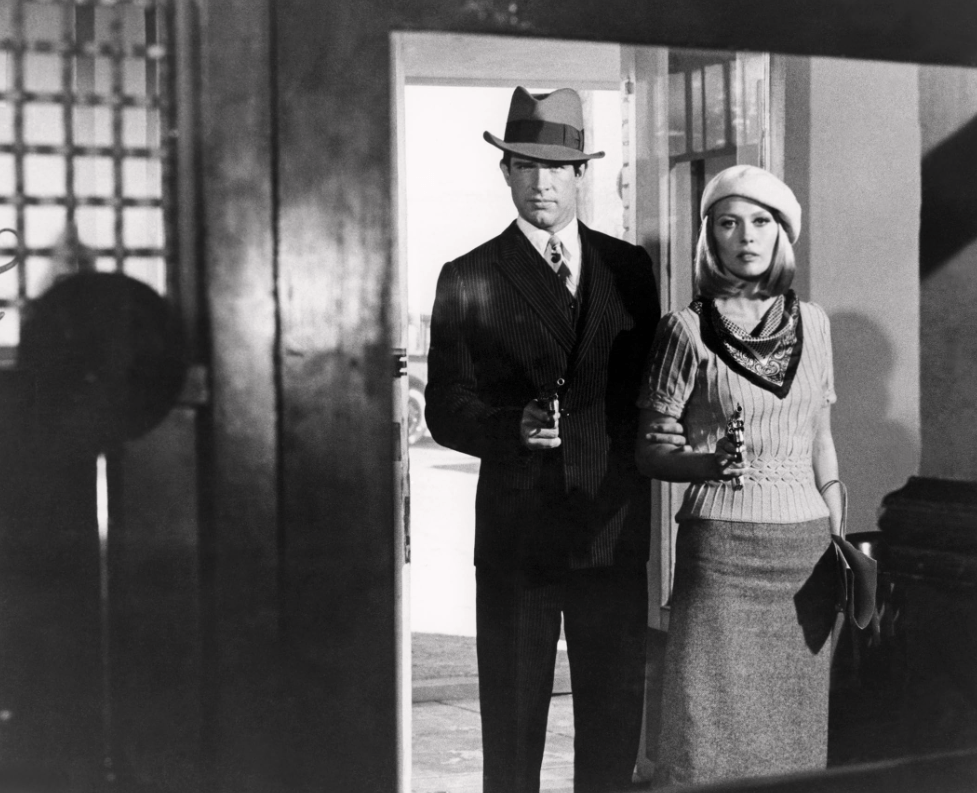

1. Bonnie and Clyde (1967)

Arthur Penn’s landmark film changed Hollywood overnight. Dunaway’s Bonnie Parker was no mere moll; she was a woman hungry for life, romance, and recognition, dressed in berets and bias-cut skirts that launched a fashion craze. The film’s balletic violence shocked audiences, but it was Dunaway’s mixture of fragility and ferocity that lingered. Pauline Kael, who championed the film, described Dunaway as embodying “a glamour that is simultaneously hard and desperate.” Without her, Bonnie and Clyde would be a crime story. With her, it became myth.

2. The Thomas Crown Affair (1968)

If Bonnie and Clyde made her an icon, Thomas Crown made her untouchable. Opposite Steve McQueen’s suave thief, Dunaway’s Vicki Anderson was the equal match: investigator, strategist, lover. Their erotic chess scene is one of the great seductions in film history—not because of nudity but because of tension, the slow calculation of two people determined to win. In a decade when Hollywood was still adjusting to the idea of female leads with agency, Dunaway redefined what it meant to be glamorous and in control.

3. Chinatown (1974)

Roman Polanski’s Chinatown is often remembered as Jack Nicholson’s film, but its power rests on Dunaway’s shoulders. As Evelyn Mulwray, she is the tragic fulcrum, concealing secrets too unbearable to articulate. The performance is an object lesson in restraint: every tremor in her voice, every glance away from Nicholson’s probing Jake Gittes, hints at trauma. The final revelation—“She’s my sister and my daughter”—would collapse under lesser actors. In Dunaway’s hands, it devastates. Few characters in American film are so indelibly haunted.

4. Three Days of the Condor (1975)

Sidney Pollack’s thriller is remembered for its paranoia, its prescient vision of government surveillance. But Dunaway complicates what might otherwise have been a standard hostage role. Her character, Kathy, becomes not merely an accessory to Redford’s fugitive but a reluctant partner, oscillating between sympathy and suspicion. It is not her most famous performance, but it underscores her ability to locate depth even in generic frameworks. In a genre dominated by masculine anxiety, Dunaway insists on her own space.

5. Network (1976)

If Chinatown was her tragedy, Network was her triumph. As Diana Christensen, the ruthless television executive who treats human breakdown as prime-time spectacle, Dunaway delivered a performance of terrifying precision. She won the Academy Award, deservedly, but more than that, she captured a cultural shift.

Critics at the time were astounded by the accuracy of Paddy Chayefsky’s screenplay but debated whether the performances tipped into caricature. What Dunaway achieved was the opposite: she grounded the satire in cold conviction. Diana is not a villain who cackles—she is a professional who believes every compromise is logical. What seemed exaggerated in 1976—the idea that television would exploit tragedy for ratings—reads today as prophecy. Watching Dunaway’s Christensen is like glimpsing the blueprint for reality television, cable news spectacle, and social media outrage culture. She didn’t play hysteria; she played the new normal before the world knew it was coming.

Dunaway later reflected on the role with a kind of astonishment: “I thought it was satire, but it turned out to be reportage.”

6. Eyes of Laura Mars (1978)

Irvin Kershner’s thriller is part horror, part fashion editorial, and wholly of its era. Dunaway plays Laura Mars, a photographer who begins to see murders through the killer’s eyes. Critics were divided, but the film has since acquired cult status, in part because of how Dunaway threads glamour and dread. She understood that the film’s premise was absurd, but she refused to play it as camp; instead, she made Laura’s visions feel like the cost of seeing too much, of being too deeply embedded in the machinery of images.

7. Mommie Dearest (1981)

No film has divided Dunaway’s legacy more. Based on Christina Crawford’s memoir of life with her adoptive mother, Joan Crawford, Mommie Dearest was intended as a serious exposé of Hollywood dysfunction. What audiences received was something closer to grand guignol. Critics dismissed it as grotesque, Roger Ebert calling it “a painful experience that masquerades as a movie.”

Yet history has been kinder. By the 1990s, the film had been reclaimed by queer audiences as camp scripture, its most outrageous scenes quoted and parodied endlessly. The “no wire hangers” moment became a cultural shorthand for maternal tyranny, but it also preserved the performance in collective memory in a way no polite biopic ever could.

Dunaway, for her part, regretted the role bitterly. “It was meant to be serious. It turned into a sideshow,” she later wrote. And yet, the very thing she disdained—the extremity of the performance—secured her immortality in popular culture.

8. Barfly (1987)

In Barbet Schroeder’s adaptation of Charles Bukowski, Dunaway shed glamour altogether. As Wanda, the weary, alcoholic companion to Mickey Rourke’s Henry Chinaski, she gave one of her most unguarded performances. No makeup tricks, no couture costumes, only a raw portrait of survival on society’s margins. Critics praised the film as a departure, proof that Dunaway could match method actors in naturalism. It remains one of her finest, and least showy, achievements.

9. Arizona Dream (1993)

Emir Kusturica’s surreal comedy-drama was a strange project, filled with eccentricities and dream logic. Dunaway, playing a woman obsessed with building flying machines, embraced the absurdity with surprising grace. It is not a canonical role, but it demonstrated her willingness, even in mid-career, to gamble on unconventional cinema. The performance, tinged with humor and melancholy, shows the durability of her curiosity.

10. Gia (1998)

By the late 1990s, Dunaway was appearing less frequently, but her role in HBO’s Gia as modeling agent Wilhelmina Cooper was a reminder of her authority. Opposite a young Angelina Jolie, she played the grande dame with elegance and gravitas, anchoring the film’s volatile energy. It was a small part, but telling: Dunaway, once the face of New Hollywood, now bridging into the new prestige television era.

The Afterlife of a Star

To view Dunaway’s career alongside her contemporaries clarifies her singularity. Fonda translated political activism into star power; Keaton made vulnerability chic; Burstyn turned empathy into gravitas; Streisand shattered conventions through sheer force of talent. Dunaway, by contrast, made alienation magnetic. She was the actress you admired but never “identified with.” Her power came not from accessibility but from distance, not from warmth but from voltage.

Her career is often remembered as volatile: peaks of genius, valleys of misfires. But this is precisely what makes her great. She was never content to repeat herself, never willing to disappear into safe character parts. She risked ridicule (Mommie Dearest), pursued genre experiments (Eyes of Laura Mars), and returned to stripped-down realism (Barfly).

The Power of Absence

By the turn of the millennium, Dunaway had largely receded from Hollywood screens. In part, this was the industry’s fault: opportunities for actresses of her stature and age were scarce. But absence itself became part of her legend. Where some stars reinvented themselves through television or second careers, Dunaway chose distance, cultivating an aura of enigma rather than ubiquity.

The stage occasionally offered her a home. She appeared in productions of Master Class—playing Maria Callas with a fierceness that mirrored her own legend—and in various revivals that highlighted her classical rigor. But she never attempted the late-career reinvention that others pursued.

Instead, Dunaway let silence do the work. Her absence from film only heightened the intensity of her earlier performances, freezing them in amber, immune to dilution. In an age of overexposure, she became the rare figure who understood that withdrawal can be as powerful as presence.

As she herself once remarked: “You cannot hold on to stardom. You can only hold on to your work.”

For an actress who had once defined the glamour and danger of a Hollywood in transition, that withdrawal feels fitting. Faye Dunaway’s greatness lies not only in what she gave us on screen but also in what she withheld. Stardom, for her, was never about being everywhere—it was about being unforgettable when she appeared, and unapproachable when she did not.