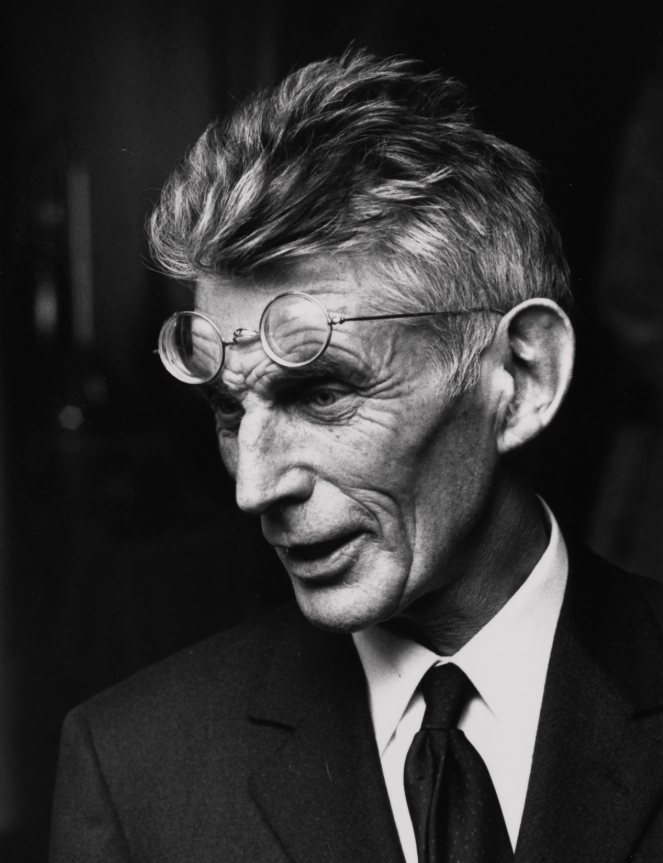

Samuel Beckett never courted the spotlight, yet the light always found him — a Nobel Prize, a place in the canon, and the dubious honor of having his work reduced to clichés about “bleakness.” To speak of Beckett as a prophet of despair is to miss the subtler, stranger truth: he was, above all, a writer obsessed with the mechanics of existence — its rhythms, its stutters, its stubborn refusal to yield meaning.

From Dublin to Paris

Born in Foxrock, Dublin in 1906, Beckett was educated at Trinity College before gravitating to Paris, where he briefly served as a secretary to James Joyce. If Joyce represented the maximalist impulse of modernism — a writer who tried to fit the world between two covers — Beckett’s trajectory was the opposite. His career was a long retreat into reduction, from the densely allusive Murphy (1938) to the minimalist prose of Worstward Ho (1983).

Beckett lived much of his adult life in Paris, even serving in the French Resistance during World War II. His wartime experiences — secrecy, waiting, the precariousness of survival — shaped the atmosphere of Waiting for Godot (1953), the play that would transform his reputation.

The Breakthrough: Waiting for Godot

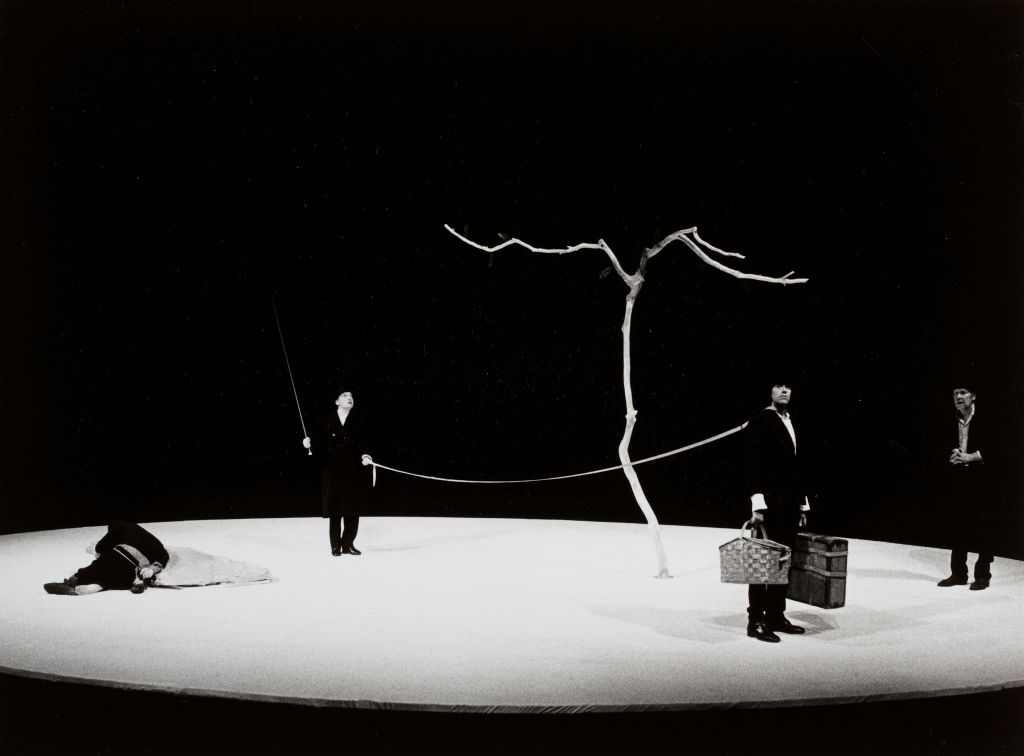

When Godot premiered in Paris, critics were baffled, even irritated. Two tramps waiting for someone who never arrives? Dialogue circling back on itself? Jokes that deflate as soon as they land? Yet audiences gradually recognized the play’s radicalism: Beckett had distilled theatre to its essentials — bodies in space, speech in time, futility as form.

The play became a touchstone of postwar culture, as resonant in Cold War Europe as in the civil rights–era United States, where an all-Black cast performed it in 1957 at a segregated Miami theater. Godot proved itself less a story than a condition: endlessly adaptable, endlessly unfinished.

Style: Reduction and Repetition

Beckett’s signature lies in his stripping away. He pares sentences down to their bare bones, leaving behind rhythms of breath and silence. His characters inhabit liminal zones — dustbins (Endgame), mounds of earth (Happy Days), nameless landscapes of rubble (How It Is). In prose, the late works often resemble incantations: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

The effect is not nihilism but exposure. Beckett forces language to confront its limits, and in doing so he reveals both its absurdity and its strange resilience.

Design and Performance

Beckett was notoriously precise about staging. His scripts dictate not only dialogue but the exact timing of pauses, gestures, even silences. The stage becomes an architectural space of austerity: a single tree, a mound of earth, a shaft of light. Designers and directors have often treated his plays as exercises in minimalism, their starkness influencing visual art as much as theatre.

Indeed, Beckett’s influence can be traced in the work of Donald Judd, Bruce Nauman, and Robert Wilson — artists who explore repetition, reduction, and the tension between presence and void.

Legacy

In 1969, Beckett was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, though he avoided the ceremony and disdained the attention. His reputation has only deepened since: he is read not just as a playwright but as a philosopher of failure, a poet of silence, a dramatist of waiting.

Yet Beckett’s greatest gift is his refusal of finality. His works resist closure, insisting instead on the persistence of speaking, moving, failing. Against despair, Beckett offers not consolation but endurance: the stubborn, absurd, faintly comic insistence on going on.

Ten Essential Works by Samuel Beckett

1. Waiting for Godot (1953)

- Context: Premiered at the Théâtre de Babylone in Paris in January 1953.

- Reception: Initial audiences were baffled, some hostile, but word of mouth and critical champions quickly established it as a landmark of modern theatre. Its London premiere (1955) at the Arts Theatre, directed by Peter Hall, cemented its reputation, though reviews were sharply divided.

- Legacy: Now the defining text of the “Theatre of the Absurd,” endlessly staged and reinterpreted — from all-Black productions in the segregated US South to prison performances where the metaphor of waiting takes on visceral immediacy.

2. Endgame (1957)

- Context: First performed in French as Fin de partie at the Royal Court Theatre, London, 1957, directed by Roger Blin.

- Reception: Critics were perplexed by its austerity, some finding it impenetrable. Yet over time it has been hailed as Beckett’s most rigorously structured drama, often described as his bleakest.

- Legacy: Frequently paired with Godot in academic discussions, it is studied for its closed-room setting, cyclical dialogue, and meditation on endings in art and life.

3. Happy Days (1961)

- Context: Premiered at the Cherry Lane Theatre, New York, 1961, directed by Alan Schneider.

- Reception: Initially seen as one of Beckett’s “lighter” plays, with Winnie’s chatter perceived as comic relief. Later critics emphasized its terrifying vision of entrapment, especially in the second act.

- Legacy: A major role for actresses (played by Billie Whitelaw, Fiona Shaw, and Juliet Stevenson), it has become a test case for the endurance of optimism under impossible circumstances.

4. Molloy (1951)

- Context: First published in French, then in Beckett’s own English translation (1955). The opening novel of his great “trilogy.”

- Reception: Critics were uncertain how to read its disjointed form, but it was quickly recognized as a radical reworking of narrative convention.

- Legacy: Often studied alongside Kafka and Joyce, Molloy exemplifies postwar European fiction’s confrontation with fractured subjectivity.

5. Malone Dies (1951)

- Context: Published in French, later translated by Beckett himself.

- Reception: Seen as darker and more abstract than Molloy, with its bed-bound narrator dismantling narrative conventions.

- Legacy: A cornerstone of Beckett’s “literature of exhaustion,” it has been read as a parody of both the Bildungsroman and the deathbed confession.

6. The Unnamable (1953)

- Context: Published in French (L’Innommable), translated by Beckett in 1958.

- Reception: Early readers found it nearly unreadable: dense, repetitive, seemingly plotless. Yet it has since been hailed as a philosophical tour de force, anticipating post-structuralist debates about language and subjectivity.

- Legacy: Frequently cited in literary theory (Blanchot, Derrida, Deleuze) as a text that embodies the impossibility of closure in narrative.

7. More Pricks Than Kicks (1934)

- Context: Beckett’s first collection of linked short stories, published in London by Chatto & Windus.

- Reception: Largely ignored at the time, it was seen as derivative of Joyce in style and content.

- Legacy: Now valued as Beckett’s “apprentice work,” introducing themes of futility and failure through Belacqua Shuah, a comic anti-hero who foreshadows Beckett’s later protagonists.

8. Krapp’s Last Tape (1958)

- Context: Premiered at the Royal Court Theatre, London, starring Patrick Magee, who became Beckett’s frequent collaborator.

- Reception: Widely praised for its innovation: the use of recorded voice as a dramatic device was unprecedented.

- Legacy: A meditation on time and regret, it is one of Beckett’s most performed short plays. The role of Krapp has attracted major actors including John Hurt and Harold Pinter.

9. How It Is (1961)

- Context: Published in French (Comment c’est), later translated by Beckett into English.

- Reception: Its fragmented, unpunctuated form baffled critics, some dismissing it as unreadable. Over time it has been embraced as one of Beckett’s most radical experiments.

- Legacy: Influential for avant-garde writers and theorists of language, it is often compared to the work of Artaud and Bataille for its raw intensity.

10. Worstward Ho (1983)

- Context: A late prose text, written in English, published by John Calder in London.

- Reception: Critics noted its aphoristic compression, reading it as Beckett’s return to pared-down essentials.

- Legacy: Its famous line “Fail better” has entered popular culture, often divorced from its original context. Academically, it is considered a quintessential statement of Beckett’s late style: minimalist, incantatory, resistant to closure.