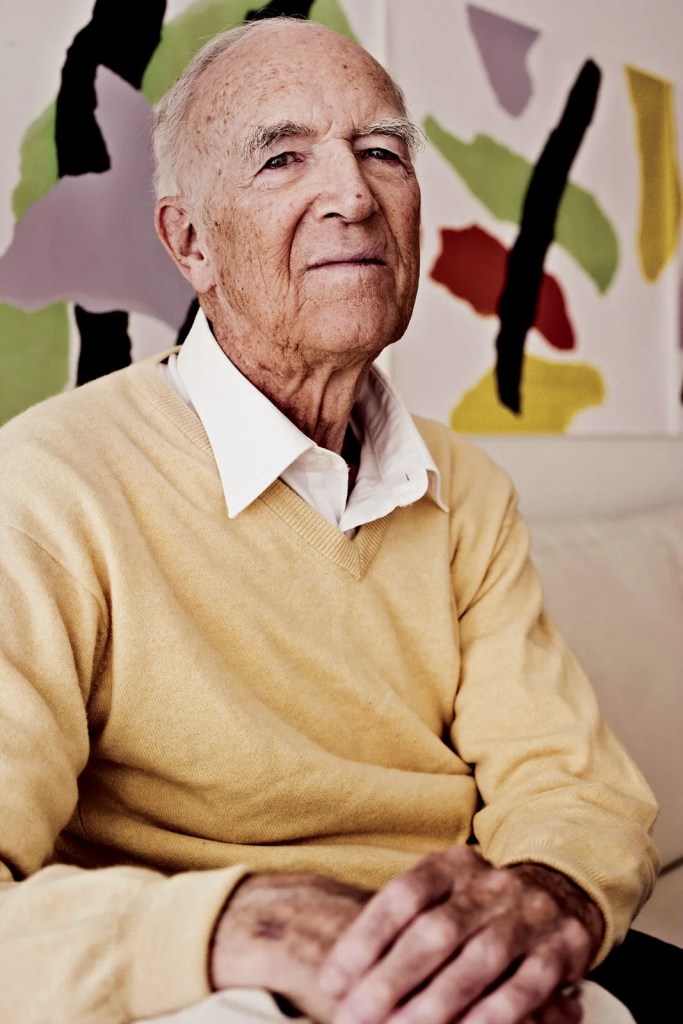

When the sails of the Sydney Opera House rise against the harbor sky, they look inevitable — as if they were always meant to be there. Yet their author, Jørn Utzon (1918–2008), was a quiet Dane who conceived one of the world’s most iconic buildings and then walked away before it was finished. His story is one of vision and exile, of a man who built not just structures but a philosophy of living with nature.

Roots in Aalborg: A Nordic Beginning

Born in Aalborg, Denmark, Utzon grew up in a shipbuilder’s family. From his father he absorbed a love of craftsmanship and the logic of structures — sails, hulls, masts — that later translated into architecture. His education at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts connected him to mentors like Steen Eiler Rasmussen and Gunnar Asplund, grounding him in the Nordic modernist tradition of functionalism tempered by humanism.

A Global Imagination

Travel shaped Utzon’s architecture as much as textbooks. Journeys to Morocco, Mexico, and China introduced him to vernacular buildings — adobe villages, Mayan platforms, Chinese courtyards — where architecture grew organically from climate and culture. Utzon later described these as “additive architecture”: buildings that accrete, grow, and harmonize, rather than impose.

This openness to the world distinguished him from many of his European contemporaries. While others looked to machines, Utzon looked to landscapes, rituals, and the sea.

The Sydney Opera House: Triumph and Tragedy

In 1957, Utzon won an international competition to design a new opera house for Sydney. His submission — abstract sketches of soaring shells — was nearly discarded, until it was rescued by the juror Eero Saarinen. What followed was one of the most daring acts of architectural imagination of the 20th century.

The Opera House’s roof, a series of interlocking shells derived from a sphere, was an engineering breakthrough. Yet political battles, cost overruns, and clashing egos drove Utzon to resign in 1966, leaving Australia before his masterpiece was complete. For decades, he never returned.

And yet: when the building was finally unveiled in 1973, it became the instant emblem of Sydney, of Australia, of modern architecture itself. In 2007, the Opera House was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage list — while Utzon was still alive, a rare honor.

- Visit Today: Sydney Opera House offers tours that highlight Utzon’s vision, with a dedicated Utzon Room honoring his design principles.

Return to Denmark: Bagsværd Church

After the Opera House, Utzon never built on that global scale again, but his later works are jewels of a more intimate, spiritual modernism. Chief among them: Bagsværd Church (1976), outside Copenhagen. From the street it is modest — white walls, low lines — but inside, a concrete ceiling undulates like drifting clouds, transforming light into something sacred.

- Visit: Bagsværd Church remains one of Denmark’s most quietly radical buildings.

Mallorca: A Life in Exile

Disillusioned with politics, Utzon made Mallorca his refuge. On the island’s northern coast he built Can Lis (1972), a family home perched above the sea, blending local sandstone with sweeping terraces. Later, he designed Can Feliz (1994), a more secluded residence further inland. Both embody his philosophy: buildings as organic continuations of their setting, places to live in rhythm with sun and sea.

- Visit: Fundació Utzon Mallorca preserves his Mallorcan legacy and offers guided tours of Can Lis and Can Feliz.

Legacy: A Humanist of Modernism

Jørn Utzon’s legacy is not only the Opera House, though that building alone secures him immortality. It is the attitude behind his work: that architecture must draw from nature, from culture, from the human need for beauty and belonging.

When asked late in life about his philosophy, Utzon said:

“The architect’s gift is to find the right place, the right materials, and the right form. Then to let nature do the rest.”

Where to Experience Utzon Today

- Sydney Opera House, Australia — sydneyoperahouse.com

- Bagsværd Church, Denmark — bagsvaerdkirke.dk

- Utzon Center, Aalborg, Denmark — utzoncenter.dk, a cultural hub dedicated to his ideas.

- Can Lis & Can Feliz, Mallorca, Spain — fundaciojutzonmallorca.org

The Last Word

Utzon’s career was marked by paradox: he gave the world its most celebrated opera house, but also its most poetic private houses; he lived in exile yet never ceased to belong to Denmark; he sought simplicity but created icons. To retrace his work is to follow a man who thought like a sailor, built like a craftsman, and dreamed like a poet.