When Annie Hall premiered in 1977, it rewrote the rules of the romantic comedy. Woody Allen’s film — intimate, self-reflexive, simultaneously comic and melancholic — offered a portrait of love not as escapist fantasy but as memory: fractured, playful, and painfully human. In a decade dominated by the epic (from Jaws to Star Wars), Annie Hall was small-scale, conversational, and distinctly personal. It won four Academy Awards, including Best Picture, and has endured as one of the most influential films of its genre.

But its endurance is not only in the lines — “La-dee-da” or “I lurve you” — nor in Diane Keaton’s iconic style. It lies in its form: a romantic comedy that dismantles itself as it unfolds, teaching us that love stories are as much about storytelling as about love.

Shop Annie Hall & Diane Keaton

Memory as Narrative

Annie Hall is structured as recollection. Alvy Singer (Allen), a comedian in his forties, looks back at his relationship with Annie (Diane Keaton). What follows is not a straightforward chronology but a mosaic of flashbacks, asides, fantasy sequences, and direct addresses to the camera. Memory here is fragmentary, ironic, unreliable. Alvy reconstructs his love affair as both analyst and participant, turning romance into narrative experiment.

This was a decisive innovation: the romantic comedy as essay-film. Annie Hall anticipates postmodern cinema in its awareness of itself as artifice, from animated interludes to split-screen psychoanalysis to subtitled interior monologues. Love becomes inseparable from the stories we tell about it — messy, contradictory, interrupted by our own neuroses.

Performance and Persona

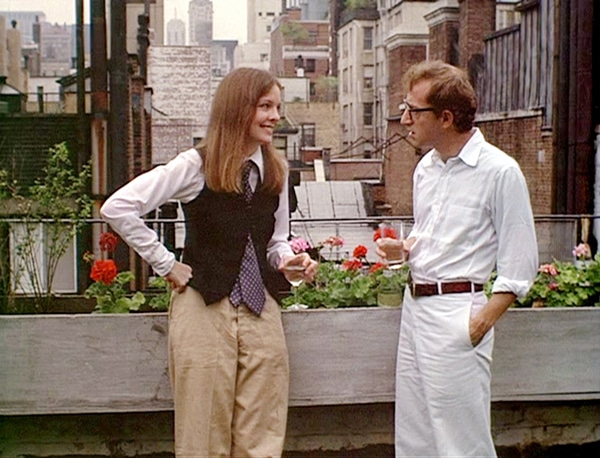

- Diane Keaton (Annie Hall): Keaton’s performance remains the film’s beating heart. Annie is awkward yet magnetic, tentative yet radiant. Her style — oversized men’s jackets, ties, loose trousers — became iconic, but her performance goes deeper: she embodies spontaneity, warmth, and an openness that counterbalances Alvy’s neurotic density. The role earned her an Oscar and made her an emblem of 1970s naturalism.

- Woody Allen (Alvy Singer): Allen plays Alvy as a semi-autobiographical creation: witty, neurotic, self-absorbed, perpetually analyzing. His comedic timing drives the film, but his presence also sharpens its ambivalence. Alvy’s charm is inseparable from his flaws; the very qualities that attract Annie contribute to the relationship’s collapse.

Their chemistry is less about conventional romance than about rhythm: the dialogue overlaps, the pauses matter, the hesitations feel lived.

Themes: Love, Language, and the City

Love as Failure

Unlike classic Hollywood romances, Annie Hall admits failure from the start. Alvy tells us in the opening monologue that the relationship ended. The film’s interest lies not in whether love lasts but in what it means while it does — the comedy of miscommunication, the poetry of small moments, the bittersweet residue of intimacy.

Language and Miscommunication

Much of the film’s humor arises from language: psychoanalytic jargon, intellectual debates, fumbling declarations. Communication becomes both bridge and barrier. The famous scene where subtitles reveal Alvy and Annie’s true thoughts under their banal chatter captures this perfectly: language is performance, and beneath it lies insecurity.

The City as Character

New York City frames the relationship, its apartments, bookshops, and cinemas shaping the couple’s rhythm. Los Angeles appears as its foil: a land of sunlight, therapy, and superficiality, where Alvy is alienated. The bi-coastal tension becomes thematic — New York as intellectual melancholy, L.A. as hollow optimism.

Cultural Context

Released in the late 1970s, Annie Hall resonated with a culture negotiating between the sexual revolution of the 1960s and the conservatism of the 1980s. It captures a generation of urban intellectuals experimenting with therapy, self-analysis, and relationships untethered from traditional structures. The film’s honesty about failure — and its refusal to punish Annie or reward Alvy — spoke to audiences weary of romantic clichés.

It also helped redefine the romantic comedy genre. Where earlier rom-coms emphasized sparkling banter and eventual union, Annie Hall prioritized psychological realism, hesitation, and ambivalence. The “romantic comedy” could now end without the couple together, yet still feel complete.

Legacy

Annie Hall became both blueprint and cliché. Its neurotic intellectual hero influenced countless films and television shows, from When Harry Met Sally to Seinfeld. Its narrative playfulness paved the way for films that blend romance with self-reflexive structure. Keaton’s style remains iconic, repeatedly referenced in fashion editorials.

Yet its legacy is complicated. Woody Allen’s personal controversies have cast long shadows over his work, prompting reappraisals of Annie Hall and debates about separating art from artist. Still, the film endures in cultural memory, not only for its wit but for its honesty about the impossibility of perfectly narrating love.

The Aftertaste of Memory

What makes Annie Hall endure is its aftertaste. It doesn’t give us lovers walking into the sunset but something closer to truth: the recognition that relationships end, yet remain inside us. Alvy concludes with a joke about needing eggs despite irrationality — a metaphor for love itself: fragile, absurd, and necessary.

For those who first saw it young, Annie Hall was not only a film but a lesson: that to love is to miscommunicate, to fail, to remember, and still to believe it mattered. Its romance is not eternal union but the stubborn insistence that even broken love deserves to be revisited, again and again, in memory.

The Children of Annie Hall

How one small, neurotic romance redefined the romantic comedy

When Annie Hall won the Oscar for Best Picture in 1977, it gave the romantic comedy a new grammar. Out went the neat trajectories of classic screwball; in came memory, miscommunication, and the acknowledgment that love stories often end in heartbreak. The films below carry its DNA — some directly, others by mutation.

When Harry Met Sally… (1989, dir. Rob Reiner, written by Nora Ephron)

Often called the most direct heir. Its premise — men and women debating whether they can be friends — echoes Alvy and Annie’s conversational rhythms. Like Annie Hall, it builds romance out of dialogue, New York neuroses, and everyday detail. Unlike Annie Hall, it offers resolution: love endures.

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004, dir. Michel Gondry, written by Charlie Kaufman)

A surrealist descendent. Memory is fragmented, reordered, erased — echoing Alvy’s fractured recollections. The film shares Annie Hall’s conviction that love is as much about the act of remembering as the experience itself. Its bittersweet conclusion — choosing love despite inevitable pain — feels like Allen’s final monologue taken to cosmic scale.

Her (2013, dir. Spike Jonze)

Romance meets technology. Joaquin Phoenix’s Theodore, like Alvy, is introspective, melancholic, verbose. His love affair with an operating system dramatizes the theme Allen staged in 1977: communication as both bridge and impossibility. The result is an Annie Hall for the digital age — intimate, awkward, tender, and unfinished.

500 Days of Summer (2009, dir. Marc Webb)

Perhaps the most openly indebted to Annie Hall in structure. It fragments chronology, offers voiceover subjectivity, and dramatizes the gap between expectation and memory. Like Alvy, Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s Tom narrates a relationship that has already ended, and like Annie, Zooey Deschanel’s Summer refuses to fit his idealized script.

Frances Ha (2012, dir. Noah Baumbach & Greta Gerwig)

Not strictly a romance, but it inherits Annie Hall’s rhythm of New York life and its focus on intimacy beyond convention. Dialogue overlaps, relationships drift, memory shapes narrative. Greta Gerwig’s Frances, like Annie, becomes iconic through her particularity — awkward, charming, and unforgettable.

The Inheritance

What Annie Hall gave cinema was permission: to let love stories be intellectual and messy, to treat memory as structure, and to admit that endings can be bittersweet without being failures.

Every time a film lingers on awkward pauses, rewinds a romance in flashback, or embraces the beauty of an imperfect ending, it tips its hat to Alvy and Annie.