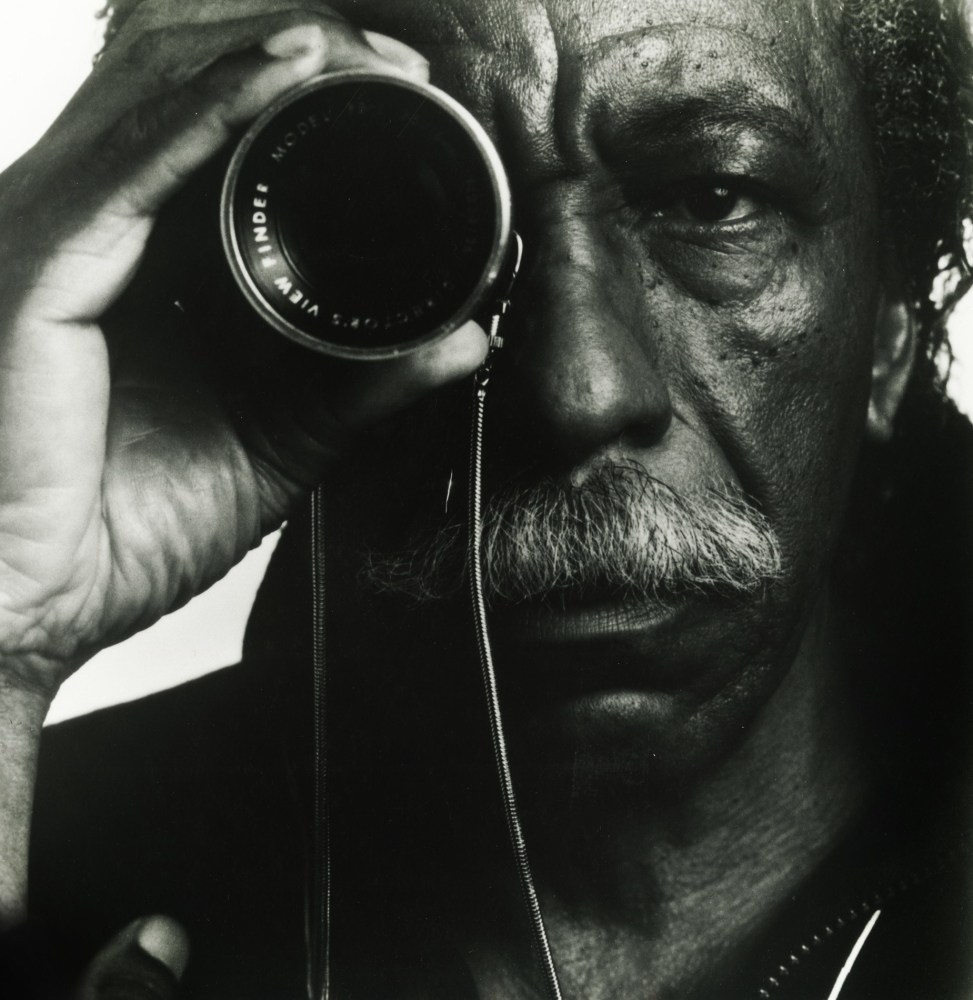

When you look through Gordon Parks’ photographs, you see more than what’s in the frame. You see longing—for justice, for dignity—behind a lens that knows both tenderness and confrontation. Parks (1912–2006) was many things: photographer, filmmaker, writer, musician. But at the core of all these roles was a mission: to see, to show, to challenge. I have never managed to look at any of his pictures without being profoundly impacted.

Origins and Early Struggles

Born in 1912 in Fort Scott, Kansas, the youngest of fifteen children, Parks grew up in a segregated America that offered him little expectation beyond hardship. His mother died when he was just fourteen, and survival often meant working odd jobs and navigating a world that sought to deny his potential.

A pawnshop camera, bought in Seattle, changed everything. Self-taught, Parks experimented with light, shadow, and everyday people, discovering that photography could be both art and weapon. In 1941, at the South Side Community Art Center in Chicago, he came into contact with artists, writers, and thinkers who confirmed what he had already begun to sense: art could bear witness.

The Camera as Weapon and Witness

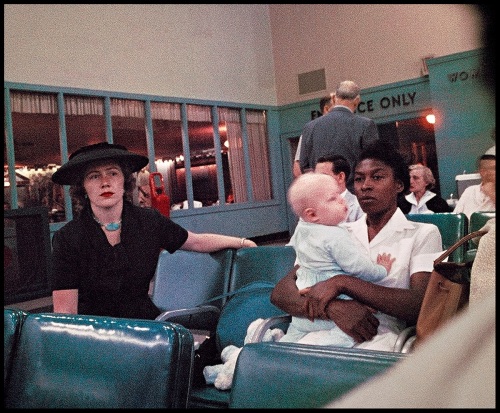

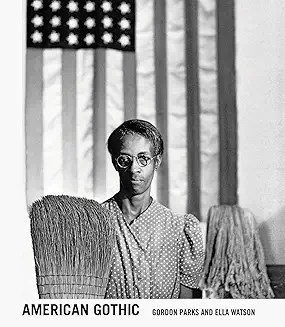

One of his earliest iconic works, American Gothic, Washington, D.C. (1942), depicts Ella Watson, an African-American cleaning woman, standing before an American flag with broom and mop in hand. A stark echo of Grant Wood’s painting, it both dignified Watson and indicted the contradictions of American democracy.

Soon after, Parks joined the Farm Security Administration under Roy Stryker, documenting poverty and inequality across the country. For him, the camera was never a neutral tool—it was moral, political, urgent.

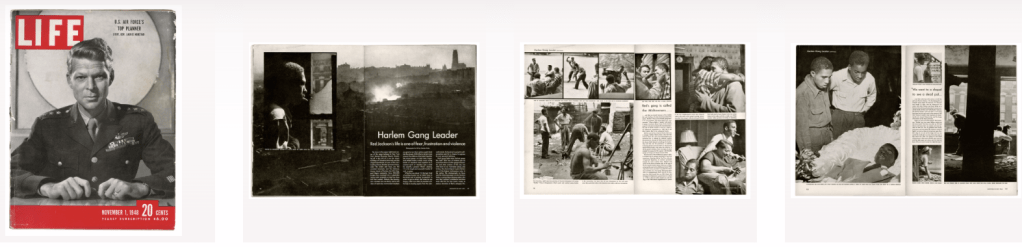

“Harlem Gang Leader” and the Making of an Argument

In 1948, Parks photographed Leonard “Red” Jackson for LIFE magazine’s essay Harlem Gang Leader. Over weeks, he captured not only violence but also resilience, intimacy, and community. Yet the final published version emphasized danger and despair—shaped heavily by editorial choices in cropping, captioning, and layout.

Decades later, the exhibition Gordon Parks: The Making of an Argument revealed how media framing can distort truth. Parks’s images carried complexity, but what the public saw was a simplified, sensational narrative. His experience underscored both the power and compromise inherent in working within mainstream media.

Beyond Photography: Writing, Film, and Music

Parks’s artistry was never confined to the still image. He wrote novels, poetry, and memoirs; The Learning Tree, his semi-autobiographical novel, became his first major film as director. Later came Shaft, Leadbelly, and Solomon Northup’s Odyssey. In these films, as in his photographs, Parks confronted questions of race, power, and identity—while also breaking barriers as one of the first Black directors in Hollywood.

He was also a composer and musician, seeing no division between the arts but rather a continuous drive to tell stories across forms.

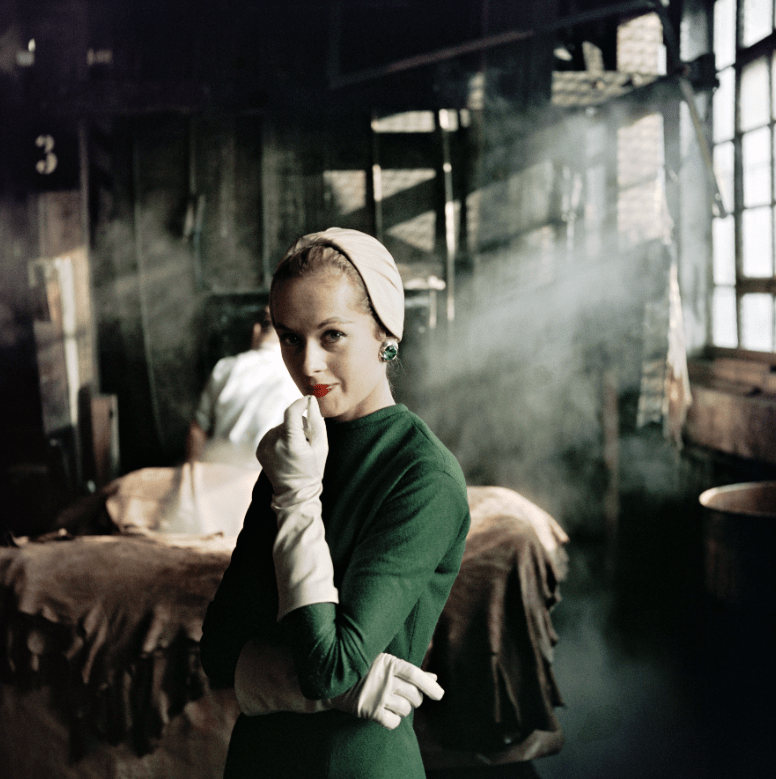

Beauty and Complexity

Parks’s work embodies tension. His fashion photography for magazines like Vogue demonstrated his mastery of elegance, light, and glamour. Yet his documentary images of segregation, poverty, and racism showed the stark realities often hidden from public view.

This duality—beauty alongside injustice—was not contradiction but conviction. Parks believed that showing dignity and grace in the face of struggle was itself a form of resistance.

Legacy and Lessons

Gordon Parks’s legacy rests on several intertwined contributions:

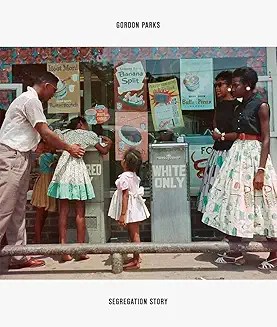

- Visual Witness: His images of segregation and injustice remain among the most powerful visual accounts of 20th-century America.

- Multidisciplinarity: He proved that art need not be bound to a single medium; photography, film, writing, and music all became tools for storytelling.

- Ethics of Representation: His career highlights how editorial decisions shape public perception, raising enduring questions about who controls narrative.

- Art as Activism: Parks never separated art from justice. For him, the act of creating was inseparable from the act of confronting.

- Beauty with Purpose: His work demonstrates that aesthetic refinement and social critique can coexist, each sharpening the other.

Books:

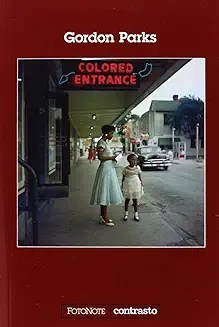

Segregation Story. Expanded Edition Hardcover – 4 July 2022

American Gothic: Gordon Parks and Ella Watson Hardcover – 16 Jan. 2024

Gordon Parks (FotoNote) Paperback – Illustrated, 5 Sept. 2013

Choice of Weapons Hardcover – 1 Jun. 1966

TL;DR

In an age of image saturation, Parks’s example feels urgent. His work reminds us to ask: Who is telling this story? Whose perspective is included, and whose is left out? He also reminds us that beauty is not frivolous—it can be a vehicle for empathy, confrontation, and change.

Gordon Parks did not simply photograph the world as it was. He revealed what it could, and should, be. His images should be mandatory to the curriculum in schools all over this fractured world of ours.

To learn more: https://www.gordonparksfoundation.org/

All images courtesy of the Gordon Parks Foundation