Few artists of the 20th century lived as many lives — and left as many indelible marks — as David Bowie. Singer, songwriter, actor, painter, fashion icon, and cultural shape-shifter, Bowie was more than a musician: he was a prism through which entire generations refracted their desires, anxieties, and dreams. From Ziggy Stardust to the Thin White Duke, from Berlin experimentalist to mainstream superstar, he lived art as metamorphosis, embodying the idea that identity itself was performance.

Early Years: From Brixton to Beckenham

Born David Robert Jones in Brixton in 1947, Bowie grew up in postwar London, a city still reeling from austerity yet already pulsing with new cultural energies. A teenage devotee of rock ’n’ roll and jazz saxophone, he reinvented himself early by adopting the name Bowie (to avoid confusion with Davy Jones of The Monkees) and cycling through a string of bands.

His early singles in the 1960s were hesitant, but his theatrical instincts set him apart. He was fascinated by mime, kabuki, and avant-garde performance — influences that would fuse with his music to create a hybrid persona unlike anything rock had seen before.

Stardust and Beyond

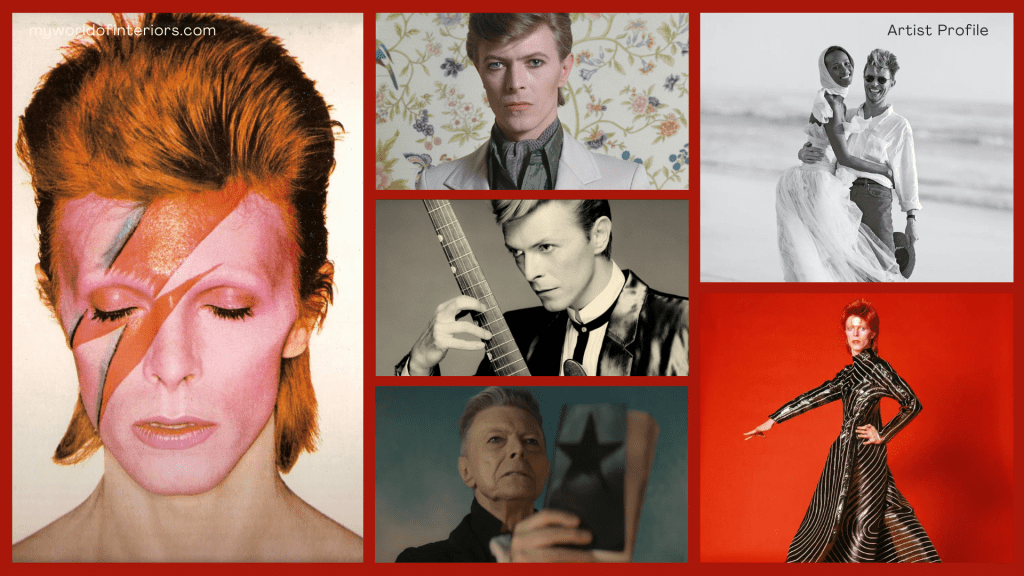

Bowie’s breakthrough came with The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (1972). Ziggy — an alien rock star descending to Earth — was as much a theatrical invention as a musical one. Bowie’s glitter makeup, androgynous costumes, and electric performances destabilized gender norms and gave voice to outsiders. For a generation of fans, Ziggy was not just a character but a possibility: that one could invent oneself anew, free from convention.

But Bowie was never content to stay still. By 1973, he killed off Ziggy on stage, leaving fans in shock. In the mid-1970s came the soul-infused Young Americans, yielding the hit “Fame” with John Lennon, followed by the cocaine-fueled Thin White Duke period and the stark experimentalism of the Berlin Trilogy (Low, “Heroes”, Lodger), produced with Brian Eno. These albums, blending electronic textures, ambient soundscapes, and fractured pop, became some of the most influential records in modern music.

Actor and Auteur

Bowie’s charisma extended beyond the recording studio. In The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976), Nicolas Roeg cast him as Thomas Jerome Newton, an alien undone by human excess. The role felt less like acting than revelation: Bowie’s otherworldly presence and fragile beauty embodied the character’s alienation.

His film career spanned decades: from his eerie turn as the Goblin King in Jim Henson’s Labyrinth (1986) to portraying Andy Warhol in Basquiat (1996), Pontius Pilate in The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), and even Nikola Tesla in Christopher Nolan’s The Prestige (2006). Each role carried the aura of Bowie’s cultural weight — his face a canvas already laden with meaning.

The Visual Artist

Less known but equally vital was Bowie’s work as a painter and collector. His canvases drew from German Expressionism and postmodern abstraction, while his collection included works by Basquiat, Frank Auerbach, and Damien Hirst. For Bowie, art was not a sideline but a dialogue with his music, another medium through which to explore identity, vision, and mood. His 1994 series The D-Head Portraits — stylized, distorted heads — reflected his fascination with masks and personas.

Reinvention and Mainstream Triumph

The 1980s brought Bowie to his broadest audience. Let’s Dance (1983), produced by Nile Rodgers, gave him massive hits — “China Girl,” “Modern Love,” “Let’s Dance” — and cemented him as a global superstar. Yet even as he filled arenas, he remained restless, experimenting with side projects like the band Tin Machine and later returning to solo work that blended electronica, rock, and jazz.

The Final Act

In 2013, after nearly a decade of silence, Bowie surprised the world with The Next Day, an album that looked backward and forward at once. Then, in 2016, came Blackstar, released just two days before his death. It was a parting gift and an artistic testament: a record steeped in jazz, mortality, and cryptic imagery. With songs like “Lazarus,” Bowie staged his own departure as performance art. He left the world as he had lived in it — transforming death itself into a final act of creation.

Legacy of an Icon

David Bowie’s legacy defies containment. He sold more than 140 million records, but statistics scarcely capture his influence. He changed how popular music could look and sound; he made androgyny glamorous, queerness visible, and reinvention not only permissible but desirable. He inspired fashion designers, filmmakers, choreographers, and generations of musicians from punk to pop to electronic.

Above all, Bowie embodied freedom: the freedom to invent oneself, to inhabit contradictions, to be many things at once. He showed that identity could be fluid, playful, and performative — and that art could be life, lived out loud.

As Tilda Swinton said at his passing, “He lived life as if it were an artwork. And it was.”

Bowie may have left the planet in 2016, but like Ziggy, he never really fell to Earth. His presence lingers — in the records that continue to seduce, the images that continue to astonish, and the countless artists who carry fragments of his vision into the future.

10 Essential Works by David Bowie

1. The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (1972)

The album that redefined glam rock and gender performance in music. Ziggy Stardust was not only a concept character but a cultural revolution, proving that rock could be theatre and identity a work of art.

2. “Heroes” (1977)

The centerpiece of the Berlin Trilogy, recorded at Hansa Studios within earshot of the Berlin Wall. Its soaring refrain, born of fractured guitar and Brian Eno’s ambient textures, became an anthem for love, resistance, and possibility.

3. Young Americans (1975)

Bowie’s “plastic soul” period yielded some of his most commercial hits, including “Fame” with John Lennon. The album marked his ability to absorb American R&B while reinventing himself yet again — from alien glam rocker to slick soulman.

4. Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps) (1980)

Often considered his best post-Berlin record, it fused avant-garde experimentation with sharp pop instincts. “Ashes to Ashes” revisited Major Tom in a darker register, showing Bowie’s genius for self-revision.

5. Let’s Dance (1983)

Produced by Nile Rodgers, this album brought Bowie his greatest commercial success. With hits like “China Girl” and “Modern Love,” it introduced him to a new global audience, proving that mass appeal need not dilute artistry.

6. Blackstar (2016)

Bowie’s final gift to the world: a jazz-inflected, experimental meditation on mortality. Released two days before his death, its songs (“Lazarus,” “Blackstar”) now read as a deliberate farewell, his most poignant act of self-curation.

7. The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976, film)

Nicolas Roeg’s sci-fi masterpiece cast Bowie as an alien undone by human excess. More than a role, it was a reflection of Bowie’s own alien persona. The film remains essential to understanding his cultural mythology.

8. Labyrinth (1986, film)

As the Goblin King Jareth, Bowie became a pop-cultural icon for a generation. The film’s mix of menace and seduction cemented his crossover into fantasy cinema, its legacy only growing with time.

9. The D-Head Portraits (1994, paintings)

Bowie’s series of stylized, expressionist heads underscored his seriousness as a visual artist. These works, shown alongside his vast personal art collection, revealed a painter deeply engaged with identity and distortion.

10. “Life on Mars?” (1971, single from Hunky Dory)

A surrealist anthem layered with irony and grandeur, it captured Bowie’s ability to combine absurdist imagery with stadium-scale emotion. Still one of his most beloved songs, it remains a touchstone of his genius.

✨ Together, these works trace Bowie’s many lives: the alien, the soulman, the Duke, the superstar, the artist, the visionary. Each incarnation was both authentic and performative, reminding us that to be David Bowie was to live as perpetual reinvention.