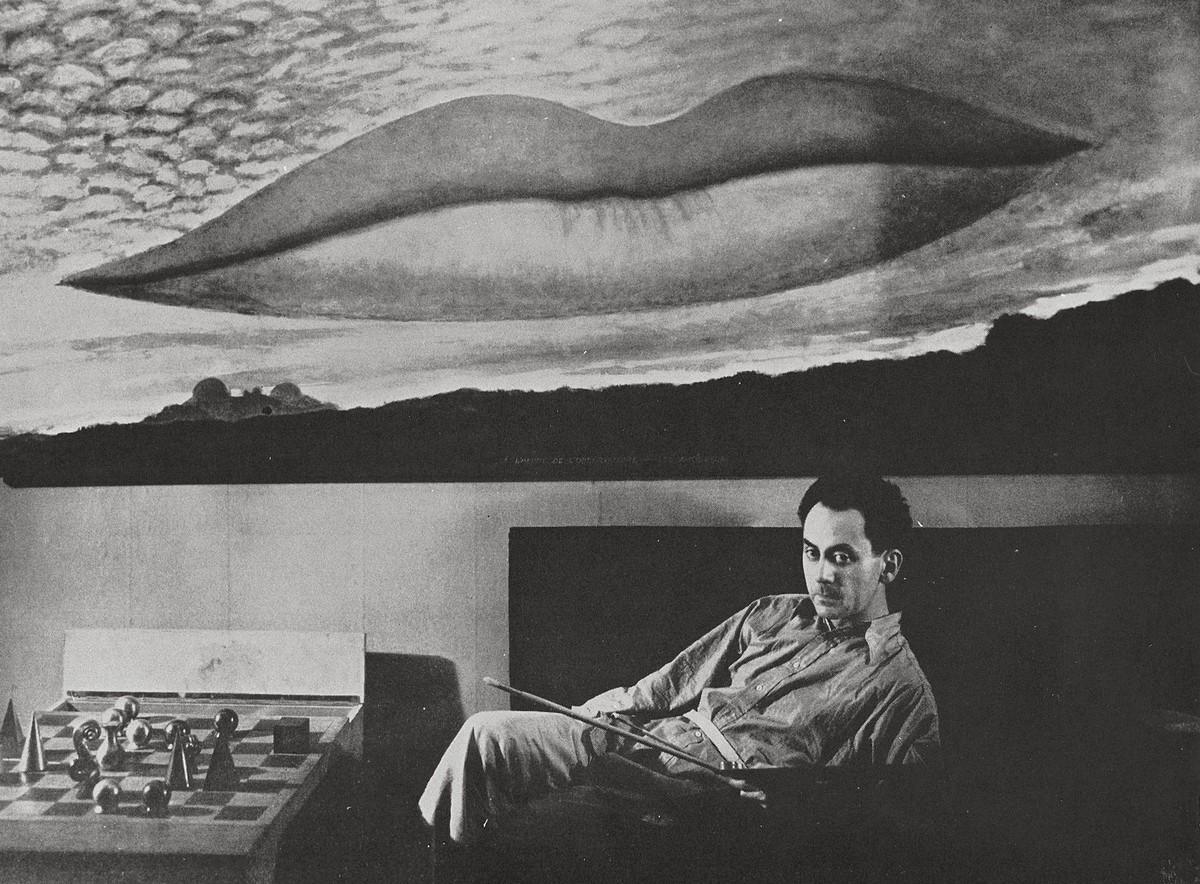

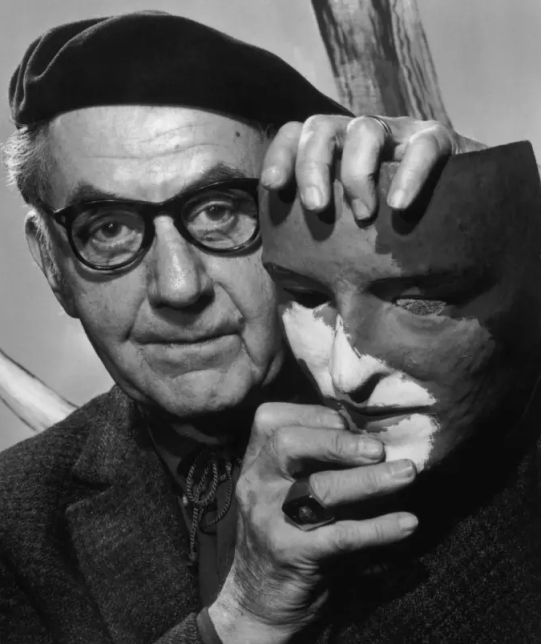

No artist embodied the restless experimentation of the twentieth century quite like Man Ray (1890–1976). Painter, photographer, filmmaker, and Surrealist provocateur, he refused categories, moving fluidly between avant-garde circles in New York, Paris, and Hollywood. His work transformed the camera from a tool of documentation into an instrument of imagination — a device capable of rendering dreams, desires, and subversions in light and shadow.

From Brooklyn to the Avant-Garde

Born Emmanuel Radnitzky in Philadelphia and raised in Brooklyn, Man Ray came of age in the ferment of early modernism. By the 1910s he was immersed in New York’s Dada movement, befriending Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia. His studio became a laboratory: canvases, constructions, and experiments with photography side by side. In 1921, drawn by Paris’s magnetic avant-garde, he relocated permanently, becoming one of the central figures of Surrealism.

The Reinvention of Photography

Although he painted throughout his life, it was photography that made Man Ray immortal. He pioneered the rayograph — camera-less photographs created by placing objects directly onto photosensitive paper, exposing them to light, and developing them into ghostly silhouettes. These images, halfway between science and poetry, embodied Surrealism’s fascination with chance and subconscious form.

Equally radical were his fashion and portrait photographs. For magazines such as Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, he turned commercial commissions into art: solarized images, distorted nudes, models transformed into abstractions. He photographed Picasso, Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, and Kiki de Montparnasse, immortalising Paris’s artistic demi-monde with wit and glamour.

The Surrealist Cinema

Man Ray also embraced film, creating experimental works such as Le Retour à la raison (1923), Emak-Bakia (1926), and L’Étoile de mer (1928). Flickering light, fragmented bodies, and dreamlike sequences extended his photographic vocabulary into moving images. These short films remain touchstones in the history of avant-garde cinema.

Women as Muse and Collaborator

Man Ray’s work cannot be separated from his relationships with women. With Kiki de Montparnasse, he produced some of his most iconic images, including Le Violon d’Ingres (1924), where her bare back becomes a musical instrument. Later, his turbulent affair with photographer Lee Miller not only inspired works but advanced technique: she is credited with helping him develop the process of solarization. In both cases, the line between muse and co-creator blurs, raising enduring questions about power, gaze, and collaboration.

Exile and Return

During World War II, Man Ray fled occupied France for Los Angeles, where he produced paintings, photographs, and assemblages, while continuing to engage with Surrealist ideas. Returning to Paris in 1951, he lived out his final decades celebrated but still restlessly experimental, moving between painting, photography, and mixed-media constructions until his death in 1976.

The Legacy of an Alchemist

Man Ray’s genius lay not in any single medium but in his refusal of boundaries. He proved that photography could be as experimental as painting, that commercial commissions could become avant-garde, and that Surrealism could inhabit fashion as easily as it did galleries. Today, his images — solarized faces, rayographs, dreamlike nudes — remain among the most iconic of the twentieth century.

His epitaph in Paris’s Montparnasse Cemetery reads simply: “Unconcerned, but not indifferent.” It captures his stance perfectly: detached yet engaged, playful yet profound, always searching for new ways to transmute reality into vision.

Five Iconic Works of Man Ray

- Le Violon d’Ingres (1924)

– Kiki de Montparnasse’s nude back transformed into a violin; a witty, erotic Surrealist icon.

– Centre Pompidou Collection - Rayographs (1920s–30s)

– Camera-less photographs of everyday objects, elevated into ghostly abstractions.

– MoMA Collection - Glass Tears (1932)

– A close-up of artificial tears on a mannequin’s face, haunting in its ambiguity.

– Getty Museum - Emak-Bakia (1926)

– Surrealist film of flickering light and fragmented images, a manifesto of experimental cinema.

– UbuWeb Film Archive - Lee Miller Solarized Portraits (1930s)

– Collaboration that turned technical accident into hallmark style.

– Victoria & Albert Museum

Museums & Archives

- Musée d’Orsay, Paris – Holds major photographic works.

- The Man Ray Trust – Official site preserving his legacy.

- J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles – Houses Glass Tears and other iconic photographs.

Books

- Man Ray: Women by Marina Warner – On his portraits and muses.

- Man Ray: The Complete Works by Arturo Schwarz – Definitive catalogue raisonné.

- Self Portrait by Man Ray – His memoir, first published in 1963.

Exhibitions

- Retrospectives at Centre Pompidou, Tate Modern, and the Smithsonian continue to redefine his place as not only Surrealist photographer but complete modernist.

TL;DR

Man Ray was not one artist but many: painter, photographer, filmmaker, Surrealist, fashion innovator. From rayographs to Le Violon d’Ingres, from Hollywood exile to Parisian return, he turned light into alchemy and blurred boundaries between art and commerce. His legacy is proof that to be modern is to be restless, playful, and endlessly experimental.