For more than four decades, Björk Guðmundsdóttir has moved through genres, art forms, and technologies with the elemental force of Iceland’s geology: eruptive, unpredictable, deeply rooted in nature, and yet astonishingly futuristic.

To speak of Björk is to speak of sound as sculpture, voice as topography, emotion as a form of design. Hers is not a career so much as an evolving ecosystem — part folklore, part science fiction, part ecstatic interiority. At every stage, she has insisted that music is not merely something to hear, but something to inhabit.

Where her earlier band, The Sugarcubes, embodied collective anarchy and surrealist cheer, Björk’s solo work inaugurated a new kind of intimacy: technologically innovative yet emotionally precise, avant-garde yet accessible, visionary yet rooted in the basic human impulse to play.

THE ORIGIN OF A VOCAL UNIVERSE

Björk’s voice is one of the great paradoxes of contemporary music: both childlike and gigantic; fragile enough to tremble, powerful enough to rupture. Her pitch bends like weather; her phrasing darts like a creature half-wild. But beneath this mythic quality lies rigour — a deep relationship with rhythm, space, and the micro-emotions between notes.

When she stepped out as a solo artist with Debut (1993), produced with Nellee Hooper, she positioned herself not as an indie refugee but as a cosmopolitan futurist. House, jazz, trip-hop, world percussion — all of it was clay for her hands. Tracks like “Human Behaviour” and “Big Time Sensuality” signalled a new hybridity: pop that refused to behave like pop.

Her breakthrough set the tone for the decades to come: a relentless reinvention of what music can be when emotional truth is allowed to exceed genre.

THE ICELANDIC SUBLIME

Iceland’s landscapes haunt Björk’s work — not as nationalist symbolism, but as a vocabulary of extremes. Volcanic pressure. Glacial quiet. Sudden ruptures. Slow melt.

You hear it most clearly on Homogenic (1997), often considered her masterpiece: strings arranged like tectonic plates, beats erupting like magma, and Björk in full elemental voice. This was the moment she became not just a musician, but a force — someone who could channel the sublime into a three-minute track.

Other artists attempt concept albums; Björk attempts entire worlds.

SOUND AS ARCHITECTURE, EMOTION AS MATERIAL

One of Björk’s greatest contributions is her refusal to separate technological experimentation from emotional vulnerability. For her, microphones are as expressive as violins; software is a kind of instrument; digital interfaces are extensions of the body.

With Vespertine (2001), she miniaturised her sound, creating a snow-globe of microbeats, whispered intimacy, and sonic embroidery. With Medúlla (2004), she removed nearly all instruments and built a cathedral of voices. With Biophilia (2011), she turned the album into a cross-media educational experiment — apps, custom instruments, a portable science classroom. With Cornucopia and Fossora, she embraced ecology, mushrooms, matriarchal grief, and climate futurism.

For Björk, each album asks a question and invents the technology required to answer it.

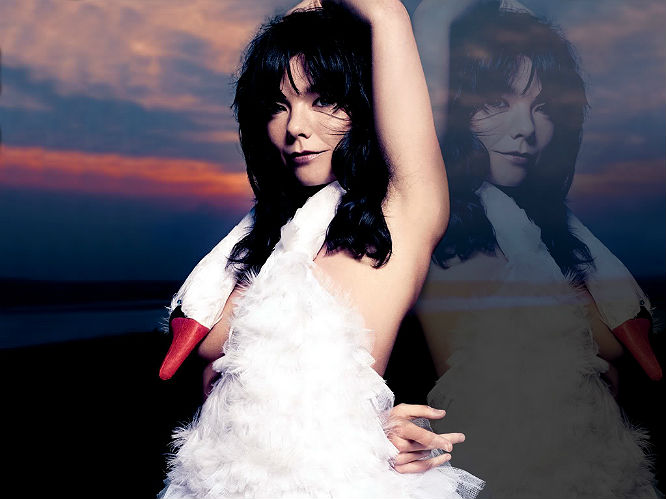

THE VISUAL MIND: COSTUME, BODY, IMAGE

To discuss Björk without discussing her visuals would be to ignore half her artistry. She treats the body as an instrument and fashion as a semiotic battlefield. Her collaborations with Alexander McQueen, Iris van Herpen, Marjan Pejoski, Nick Knight, and Michel Gondry are not merely styling choices — they are architectural extensions of the music.

Her looks are never decorative; they are conceptual exoskeletons.

She wears ideas.

THE FUTURE OF FEELING

Björk’s legacy is not defined by innovation alone. It is defined by an emotional clarity that cuts through even her most complex sonic experiments. Her music is often described as strange, but listen closely and you find something profoundly recognisable: longing, tenderness, awe, grief, mischief, erotic delight, curiosity about the world.

She remains a rare artist who treats emotion not as sentiment, but as a discipline — something to study, sculpt, and expand.

In doing so, Björk has taught an entire generation that the future of art is not about predicting technology. It is about expanding what it means to feel.

BJÖRK THROUGH THE YEARS

1977 — Child Prodigy

Releases a self-titled album at age 11 in Iceland; becomes a local curiosity and cult figure.

1980s — Punk & Art Collectives

Joins various Reykjavik underground groups, including Tappi Tíkarrass and Kukl.

1986–1992 — The Sugarcubes Era

Achieves international recognition with the surrealist alt-rock collective.

1993–1997 — Global Breakthrough

Debut, Post, and Homogenic establish her as a cultural futurist.

2000s — Experimental Ascendancy

From the hushed interiority of Vespertine to the vocal architecture of Medúlla.

2010s — Multimedia Visionary

Biophilia, exhibitions, VR experiments, and a widening interdisciplinary practice.

2020s — Post-Nature, Post-Genre

Utopia and Fossora explore ecology, feminine futurism, and grief transformed into growth.

DISCOGRAPHY

Björk (1977)

Her childhood debut — charming, folkloric, a precursor rather than part of her canon.

Debut (1993)

A dazzling entry into solo stardom. House, jazz, and world rhythms meet avant-pop curiosity.

Post (1995)

Chaotic in the best way: volcanic experimentation, club culture, and cinematic ballads.

Homogenic (1997)

Strings and beats forged into Icelandic geology. One of the defining albums of modern music.

Selmasongs (2000)

A companion to Dancer in the Dark — fragile, aching, theatrical.

Vespertine (2001)

Intimacy miniaturised: microbeats, icy beauty, whispered worlds.

Medúlla (2004)

A nearly all-vocal album — primal, corporeal, architectural; a radical rethinking of voice.

Drawing Restraint 9 (2005)

Collaboration with Matthew Barney — ritualistic, experimental, challenging.

Volta (2007)

Percussion-heavy, global, fiery; a political and energetic pivot.

Biophilia (2011)

An ecosystem rather than an album — apps, science, custom instruments, educational outreach.

Vulnicura (2015)

Raw, orchestral, devastating: a breakup album of mythic emotional clarity.

Utopia (2017)

Flutes, birdsong, eco-futurism; a vision of a hopeful matriarchal world.

Fossora (2022)

Mushrooms, matriarchy, bass clarinets; grief turned into a fertile underworld.