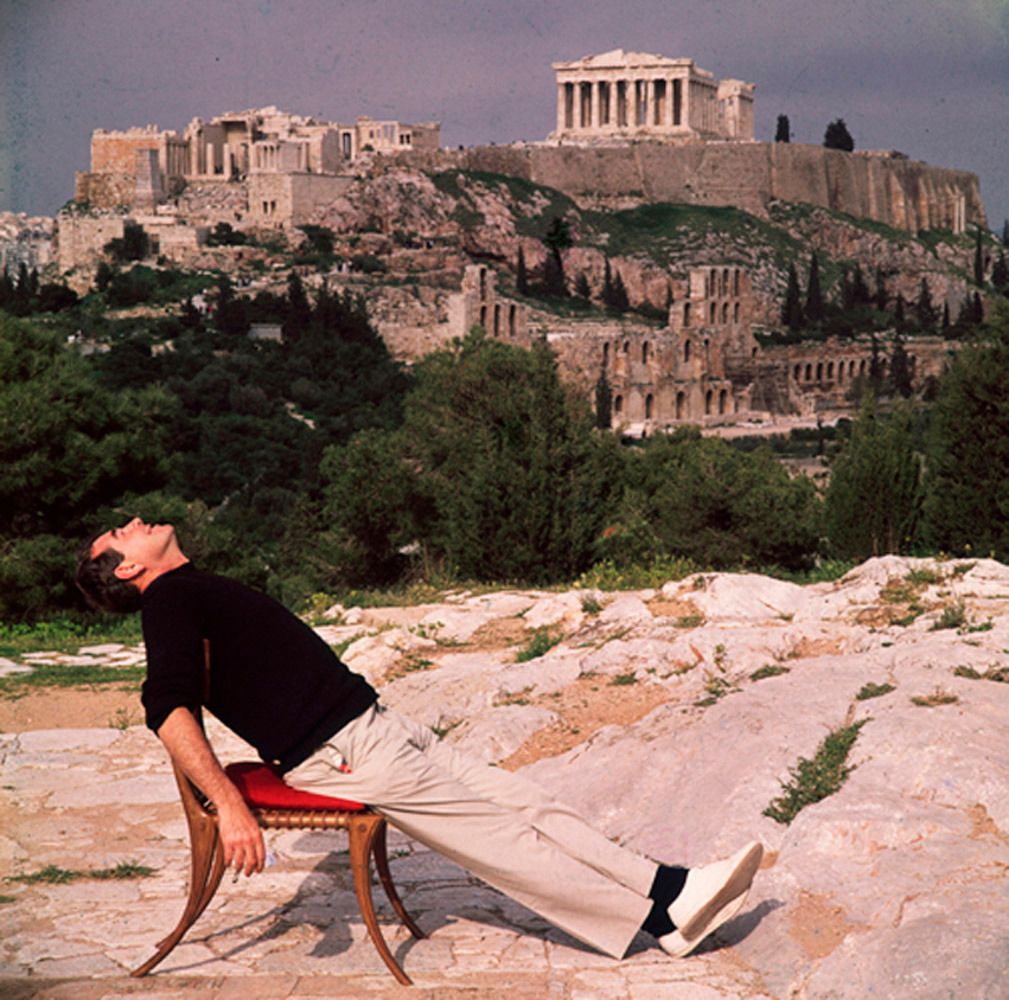

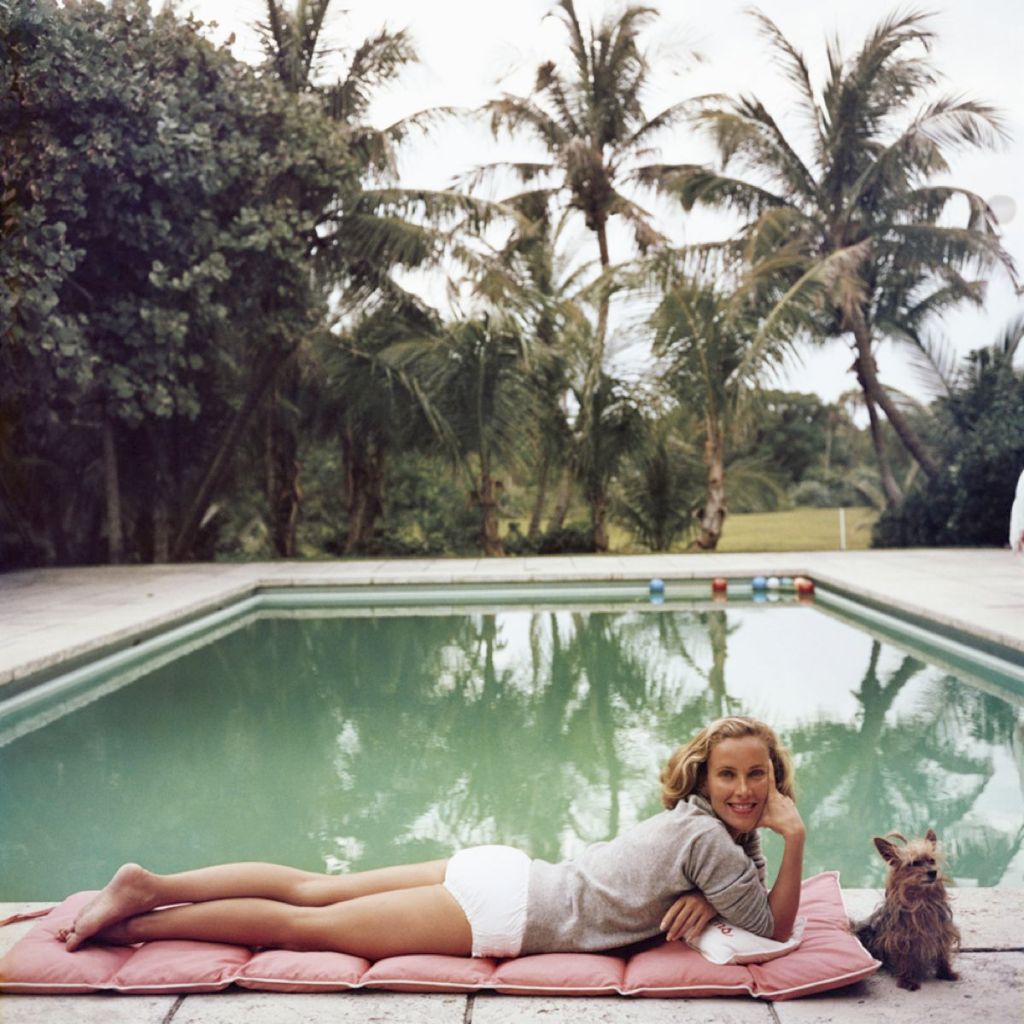

“Attractive people doing attractive things in attractive places.” Slim Aarons’ pithy description of his own work became both motto and myth. For decades, he chronicled the leisure class — sun-dappled heiresses in Palm Beach, bronzed movie stars in Palm Springs, aristocrats lounging on the Côte d’Azur. His images became shorthand for mid-century glamour: candid yet composed, casual yet impossibly chic. But behind the Technicolor sheen lies a more complex story — of a man who turned his back on war photography to invent a new visual lexicon of wealth, aspiration, and lifestyle.

From Soldier to Social Chronicler

George Allen Aarons was born in 1916 in Manhattan and raised in rural New Hampshire. He served as a combat photographer during World War II, documenting battlefields for the U.S. Army. Those years left him disillusioned with violence, and when the war ended, he made a vow: never again would he photograph death or destruction. Instead, he turned his lens toward the opposite — beauty, leisure, escape.

By the 1950s, he was photographing Hollywood stars for Life, Holiday, and Harper’s Bazaar. But unlike studio portraitists, Aarons embedded himself in the environments of the rich and glamorous. He wasn’t interested in publicity stills; he wanted lifestyle. A young Lauren Bacall sunning herself by a pool said more than a carefully lit studio portrait.

The Invention of Lifestyle Photography

Aarons’ gift was timing. Postwar America had entered an age of affluence, where suburban lawns, jet travel, and resort culture became aspirational touchstones. He translated this zeitgeist into imagery. At a time when paparazzi were growing aggressive, Aarons offered intimacy without intrusion. His subjects — C.Z. Guest, Babe Paley, Gianni Agnelli, the Gettys, the Windsors — let him in because he was not threatening. He moved through Palm Beach, Palm Springs, Capri, Gstaad, and St. Tropez with insider ease.

His photographs were deceptively candid. A group of women in Pucci dresses by a turquoise pool, polo players pausing for champagne, a family in crisp whites on manicured lawns — all felt spontaneous, yet were meticulously framed to balance glamour with informality. Aarons invented a style of photography that prefigured both lifestyle advertising and Instagram aspiration.

The Myth of Access

Vanity Fair has long noted that Aarons’ genius was not simply aesthetic but social. He cultivated access with the ease of a man who belonged everywhere yet nowhere. He wasn’t born into the world he photographed, but he learned to navigate it. He knew when to flatter, when to disappear, and when to catch a subject mid-gesture. In return, the elite gave him something rare: unguarded moments.

Aarons was not a critic of privilege, nor a cheerleader. He was a chronicler. Some accused him of glorifying inequality, others of mocking his subjects by revealing their eccentricity. The truth lies in between. His pictures shimmer with both admiration and irony, embodying the paradox of glamour — enviable yet faintly absurd.

Legacy in Print and Memory

In 1974, Aarons published A Wonderful Time: An Intimate Portrait of the Good Life, a book that crystallized his reputation. It sold modestly then, but later became a cult object, influencing generations of designers, photographers, and tastemakers. Subsequent collections — Once Upon a Time, Poolside with Slim Aarons, Slim Aarons: Women — reintroduced his archive to new audiences hungry for retro escapism.

Today, his images are fixtures in design showrooms, luxury hotels, and coffee-table books. They represent not only a bygone era but also an enduring fantasy: leisure without labor, beauty without blemish, wealth without worry.

Why Slim Aarons Still Matters

In an age when lifestyle is curated on Instagram and TikTok, Aarons looks prophetic. He anticipated the idea that life itself could be staged as an endless performance of elegance. Yet unlike social media, his images retained mystery. There is no oversharing, no captions of confession — only poise, sunlight, and suggestion.

Aarons’ legacy is double-edged. He gave us images of privilege that still seduce, but also raise questions: who gets to live this way, and why do we want to watch? His work is both a celebration and a critique, a vision of a gilded world that remains both aspirational and unattainable.

Selected Images

- Poolside Gossip (1970) – Palm Springs, two women in Pucci by Richard Neutra’s Kaufmann House. Getty Images Archive

- Kings of Hollywood (1957) – Clark Gable, Van Heflin, Gary Cooper, and James Stewart in tuxedos at New Year’s. Getty Images Archive

- C.Z. Guest at Home (1955) – The socialite posed elegantly in her Long Island garden. Getty Images Archive

- Hotel du Cap-Eden-Roc (1969) – Guests dive into the azure waters of Antibes. Getty Images Archive

- Verbier Vacation (1964) – Skiers in vibrant attire resting in the Swiss Alps. Getty Images Archive

TL;DR

Slim Aarons died in 2006, but his photographs remain vivid, circulating endlessly in galleries, design magazines, and digital feeds. They endure because they are more than pictures of the wealthy; they are images of longing, of a desire for ease and beauty that transcends class.

As much as Aarons chronicled a world, he also created one. His poolside parties, Alpine ski lodges, and Palm Springs terraces became archetypes of leisure, shaping how we imagine the good life. In the end, Slim Aarons did not just photograph glamour — he made it immortal.