Few photographers have unsettled the boundaries of art, beauty, and truth as profoundly as Diane Arbus. Born in New York in 1923 into the Russek fur dynasty, she seemed destined for a life of privilege, yet she turned her lens away from society’s glittering surfaces. Instead, she sought out what others averted their gaze from: the marginal, the eccentric, the performers, the people who existed in the edges of mid-century American life.

From Fashion to Fracture

Arbus began, conventionally enough, in fashion. Alongside her husband Allan, she photographed for Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar. But fashion, for her, became a kind of gilded cage. The studio lights and airbrushed perfection left her restless. By the late 1950s she broke away, studying with Lisette Model, who urged her to confront reality rather than idealize it.

Arbus took that advice to its limit. She prowled Coney Island, hotel rooms, sideshows, Central Park. She sought the people others ignored — giants, dwarfs, drag queens, nudists, circus performers, families that felt not quite ordinary but somehow hyper-ordinary, so that every wrinkle and freckle carried an almost unbearable intensity.

The Arbus Aesthetic

Her images, often made with a square-format Rolleiflex camera, are stark and direct. The twin lenses allowed her to maintain eye contact with her subjects while shooting, producing portraits that feel unsettlingly intimate.

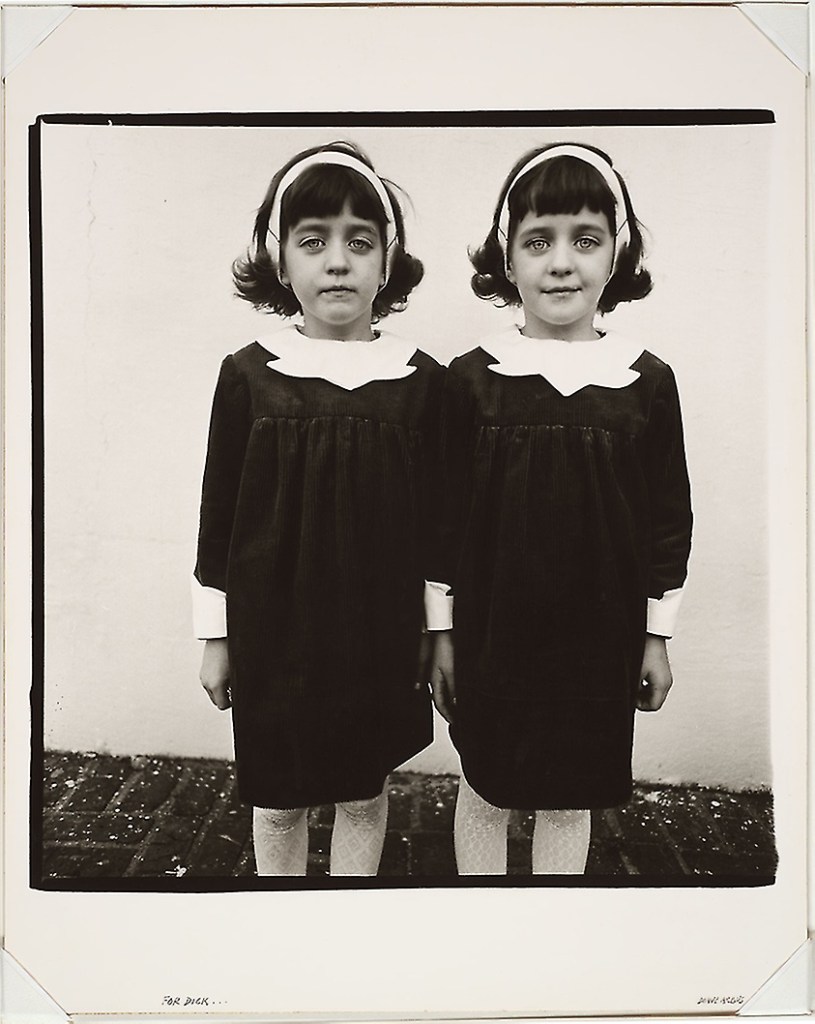

The result was an aesthetic that seemed both compassionate and clinical. Identical Twins, Roselle, N.J. (1967) remains one of the most recognizable photographs of the twentieth century: two little girls in matching dresses, standing hand-in-hand, one smiling, one frowning, their sameness fractured by the smallest difference.

Arbus’s subjects look back at us with an unnerving directness, complicating the traditional hierarchy of photographer and subject. Are we gazing at them, or are they gazing at us?

Between Empathy and Exploitation

Arbus has always provoked debate. Admirers see her work as radical empathy — a willingness to confront the hidden lives of America with respect and clarity. Critics argue that she exploited her subjects, aestheticizing their difference for the consumption of a gallery audience.

The truth lies in the tension. Arbus refused to resolve it, and that refusal is why her work continues to matter. She showed that photography is not neutral; it is an encounter, fraught, charged, sometimes tender, sometimes cruel.

Legacy of a Troubled Vision

In 1971, at the age of 48, Diane Arbus took her own life. Her posthumous retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art the following year was the first for a female photographer and remains one of the most attended exhibitions in the museum’s history.

Her influence is everywhere: in Nan Goldin’s diaristic intimacy, in Cindy Sherman’s performance of identity, in fashion editorials that flirt with the eerie or uncanny. She taught artists that the margins of society are not peripheral but central to understanding who we are.

The Mirror and the Mask

To look at an Arbus photograph is to confront the possibility that normality itself is a mask — that the suburban family portrait or the smiling debutante may be no less strange than the carnival performer or the drag queen.

Her work endures because it unsettles. It collapses the distance between “us” and “them,” reminding us that difference is not aberration but mirror. Diane Arbus remains one of photography’s most haunting figures: the woman who forced us to look, and in looking, to recognize ourselves.

Five Essential Diane Arbus Photographs

Identical Twins, Roselle, New Jersey (1967)

Two young girls in matching dresses, one smiling, one frowning — a portrait that has become an icon of the uncanny, often cited as the inspiration for Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining.

A Young Man in Curlers at Home on West 20th Street, N.Y.C. (1966)

A drag performer preparing for the night, captured in intimate domesticity. The photograph collapses public performance and private vulnerability.

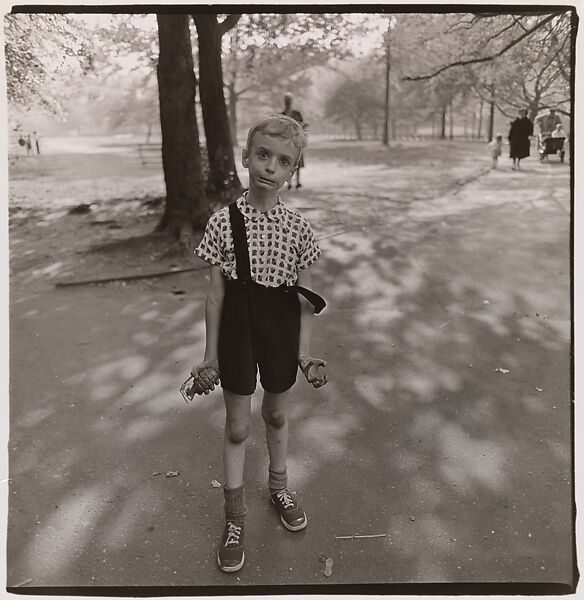

Child with a Toy Hand Grenade in Central Park, N.Y.C. (1962)

A boy gripping a toy grenade with one hand clawed and face contorted — innocence and aggression suspended in a single frame.

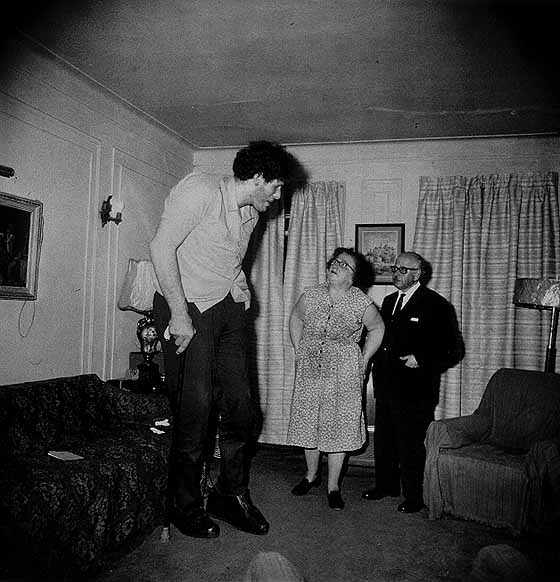

A Jewish Giant at Home with His Parents in the Bronx, N.Y.C. (1970)

A towering man looms over his small, seated parents in their living room — a family portrait both affectionate and deeply unsettling.

A Family on Their Lawn One Sunday in Westchester, N.Y. (1968)

A suburban tableau: father reclining, mother sunbathing, children scattered. At once ordinary and surreal, it exposes the strangeness within the everyday.