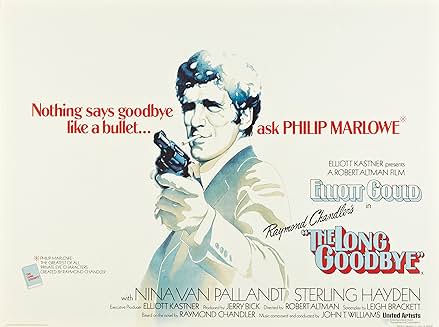

When Robert Altman released The Long Goodbye in 1973, the film was met with bewilderment. Audiences expecting a classic Raymond Chandler adaptation were confronted instead with a languid, ironic, and deeply disenchanted vision of Los Angeles. Altman transformed Chandler’s hard-boiled detective story into a commentary on America’s crumbling myths in the early 1970s — a film that is as much about the collapse of genre as it is about murder and betrayal.

Noir in the Age of Watergate

Chandler’s The Long Goodbye (1953) had originally situated private detective Philip Marlowe within the postwar malaise of American life. By the time Altman revisited the story two decades later, the social fabric had shifted: Vietnam, Watergate, and countercultural disillusion had eroded faith in institutions. Altman responded not with a faithful adaptation, but with a radical revision.

Unlike the tight, shadowy compositions of 1940s film noir, Altman bathed his Los Angeles in sunlight. His Marlowe (played by Elliott Gould) drifts in a haze of cigarette smoke and bemusement, muttering to himself as if out of step with the world. The choice was deliberate: a detective conceived in the 1930s suddenly adrift in the 1970s.

Design and Cinematic Style

Altman’s visual strategy was revolutionary for noir:

- The Sunlit Noir: Cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond employed “flashing” techniques (pre-exposing film stock) to wash the images in a hazy, faded light — a visual metaphor for memory, disillusion, and entropy.

- The Apartment as Character: Marlowe’s shabby high-rise flat, with its clutter, stale air, and view over a modernist Los Angeles, becomes a symbol of alienation. The apartment’s design reflects the 1970s shift from noir’s seedy alleys to sterile urban sprawl.

- Fluid Camera Work: Altman’s trademark long takes and drifting camera unmoor the viewer, resisting the clean logic of classic noir’s tight framing.

The aesthetic both acknowledges noir’s heritage and undermines it — a noir drained of shadows, left only with sun-bleached despair.

Fashion and Cultural Context

Marlowe’s crumpled gray suit, never changing throughout the film, is itself a costume of alienation. He is a man from another era, unable or unwilling to update his wardrobe for the 1970s. Against him, the other characters embody contemporary archetypes: yoga-practicing neighbors, New Age gurus, gangster chic. The contrast is pointed: Marlowe is an anachronism, stranded in a Los Angeles remade by counterculture and commercialism.

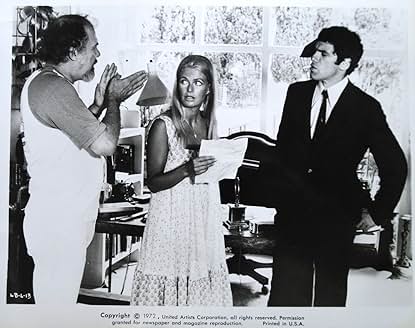

Carolyn (played by Nina Van Pallandt) epitomizes the 1970s bohemian glamour — loose hair, flowing garments, and an understated Euro-chic sophistication. The gangsters, meanwhile, exude a vulgar modernity, clad in flashy suits that nod to both Las Vegas and Hollywood excess.

The film becomes a sartorial archive of its moment: Los Angeles as a site where old myths of masculine heroism collide with the casual, commodified cool of the 1970s.

In Context with Contemporaries

Altman’s The Long Goodbye sits in dialogue with other early 1970s re-imaginings of noir and detective tropes:

- Roman Polanski’s Chinatown (1974): Where Altman bathed noir in sunlight, Polanski returned to the genre’s 1930s origins, embedding corruption within the founding myths of Los Angeles itself.

- Arthur Penn’s Night Moves (1975): Another disenchanted detective story, with Gene Hackman as a PI who can’t make sense of the mystery he’s trapped in — echoing Marlowe’s bewilderment.

- Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation (1974): Though not a detective film per se, its paranoid surveillance aesthetic shares Altman’s concern with the collapse of certainty in a post-Watergate era.

Together, these films formed the backbone of “neo-noir,” but Altman’s was the most subversive — dismantling the detective himself.

Music as Motif

John Williams’ score, written as a single theme repeated in endless variations — cocktail lounge, jazz, funeral dirge — underlines the film’s circularity. Just as Marlowe drifts without resolution, the music insists on recurrence without progress. The theme becomes both ironic and haunting, a sonic embodiment of Altman’s worldview.

Legacy

Initially dismissed as incoherent and unfaithful, The Long Goodbye has since been recognized as one of Altman’s masterpieces. Its washed-out palette, meandering narrative, and ironic detachment anticipate the postmodern films of the Coen Brothers and Paul Thomas Anderson. Elliott Gould’s offbeat Marlowe, once criticized as unserious, is now understood as an inspired re-casting of the detective as cultural ghost.

Altman redefined noir for a disenchanted age: a genre once about shadow and mystery, now exposed under the unrelenting California sun.

Design Notes: Interiors, Architecture, and Costumes

Marlowe’s Apartment

- Setting: A high-rise unit in Hollywood, facing the glass-and-steel modernist landscape of 1970s Los Angeles.

- Design Character: Cluttered, dimly lit, filled with books, cigarette smoke, and a perpetually hungry cat. The interiors stand in deliberate contrast to the sleek surfaces of the city outside. It feels more like a 1940s relic transplanted into the wrong decade.

- Visual Symbolism: The apartment embodies Marlowe’s stagnation — a man refusing to update his life as the world modernizes around him.

Los Angeles as Character

- Architecture: Unlike classic noir, which found poetry in alleys and rain-slick streets, Altman’s camera roams through glass towers, beachfront properties, and winding canyon roads. Los Angeles is depicted as both sprawling and sterile — a city of sunshine with a hollow core.

- Contrast: Marlowe’s worn suit against the gleam of Beverly Hills mansions highlights his alienation within a city obsessed with surfaces.

Costume Design

- Philip Marlowe (Elliott Gould): A single, crumpled gray suit worn throughout the film. It resists the 1970s fashion cycle entirely, marking him as a displaced figure. His suit is armor, habit, and costume all at once.

- Carolyn (Nina Van Pallandt): Flowy dresses, loose hair, natural tones — Euro-bohemian glamour that captures the aspirational ease of 1970s California.

- Gangsters: Shiny fabrics, open collars, gold accessories. Their look borders on parody — an intentional contrast to Marlowe’s understated anachronism.

Graphic Motifs

- The Cat: Marlowe’s cat, disappearing early in the film, becomes a metaphor for loyalty and loss — echoed in Altman’s refusal to tie up narrative loose ends.

- The Recurring Song: John Williams’ endlessly repeating “The Long Goodbye” theme is treated as mise-en-scène: performed in nightclubs, hummed on radios, even played in a funeral procession. It becomes a motif of Los Angeles’ emptiness — the same tune in infinite variations.