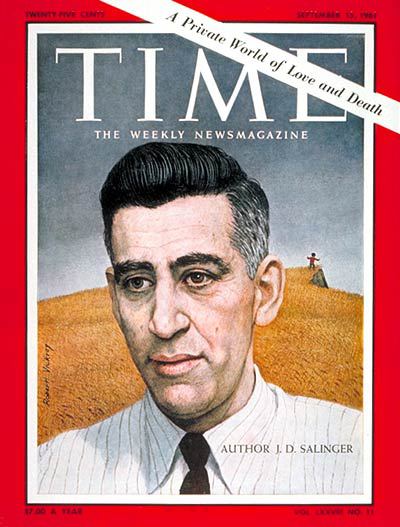

J.D. Salinger (1919–2010) remains one of the most fascinating paradoxes in American letters. Lauded as the author of The Catcher in the Rye, a book that gave adolescent alienation its most enduring voice, he also became a cultural riddle: a man who spent the last half of his life in near silence, publishing nothing, and fiercely guarding his privacy. His legacy is both luminous and shadowed — a story of genius and withdrawal, but also of troubling personal contradictions.

Shop J.D. Salinger here.

The Rise of a Voice

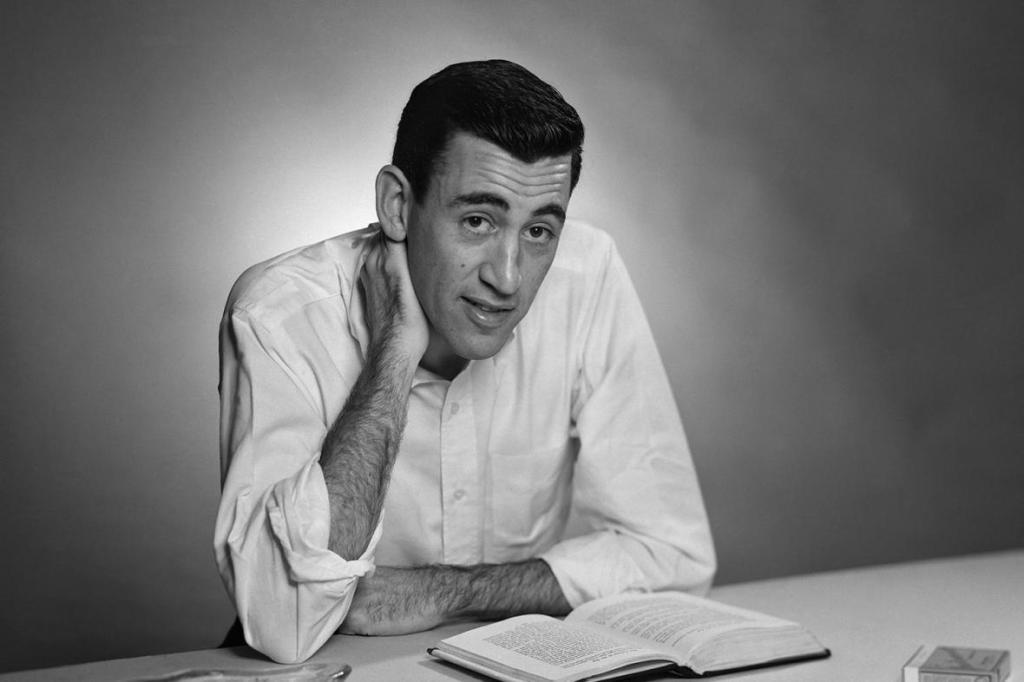

Born in Manhattan to a prosperous Jewish father and an Irish Catholic mother, Salinger grew up in a household that was both aspirational and strained. A restless student, he drifted through prep schools before finding a calling in writing. His earliest efforts appeared in magazines in the late 1930s and early ’40s, often slick and sentimental, but already tinged with the voice that would become unmistakable: colloquial, wry, and alienated.

World War II transformed him. Drafted in 1942, Salinger served with the 4th Infantry Division and participated in D-Day, the Battle of the Bulge, and the liberation of concentration camps. The trauma of war left him scarred — he suffered what we would now call PTSD — but it also deepened the psychological intensity of his work. Even in the foxholes, he carried chapters of a novel-in-progress about a young man named Holden Caulfield.

Catcher in the Culture

When The Catcher in the Rye was published in 1951, it landed like a thunderclap. Critics were divided — some dismissed it as obscene, trivial, or too colloquial — but readers, especially young readers, recognized themselves in Holden’s voice. The novel became an emblem of teenage angst and postwar disaffection, its slang and candor breaking literary taboos.

By the mid-1950s, Salinger was famous, wealthy, and increasingly disenchanted with fame. He continued to publish extraordinary stories — “Franny and Zooey,” “Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters,” “Seymour: An Introduction” — many of them revolving around the fictional Glass family, brilliant, wounded siblings grappling with spirituality and disillusionment. His work fused Zen Buddhism, Vedanta philosophy, and a fierce critique of American materialism. Yet his readership, hungry for another Catcher, often struggled with the dense, mystical, almost sermon-like qualities of his later stories.

The Retreat from the World

By the 1960s, Salinger began to vanish. He stopped giving interviews, withdrew from New York’s literary circles, and refused book publicity. In 1965 he published “Hapworth 16, 1924” in The New Yorker — a long, controversial letter-story that baffled critics — and then published nothing again in his lifetime. Instead, he lived in near-seclusion in Cornish, New Hampshire, writing daily but guarding his manuscripts with almost religious ferocity.

That retreat, however, was not without shadows. Accounts later surfaced of his relationships with much younger women, including teenage partners, which cast a troubling light on the man behind the work. These revelations complicate the myth of the reclusive genius, reminding us that his silence concealed complexities both artistic and personal.

Legacy and Unanswered Questions

Salinger’s influence is incalculable. The Catcher in the Rye has sold more than 70 million copies worldwide, shaping generations of readers and writers — from Sylvia Plath to Bret Easton Ellis. Its cadences echo in contemporary fiction, its themes of authenticity and alienation as relevant in the age of TikTok as they were in the 1950s.

And yet the enigma remains. After his death in 2010, his estate confirmed that he had continued to write for decades in secrecy, with plans to release the manuscripts in stages. Readers still wait, unsure whether Salinger’s unpublished work will alter his place in the canon — or cement him as the most tantalizing literary phantom of the twentieth century.

The Last Word

Perhaps the truest measure of Salinger’s legacy is the paradox he embodied: a writer who captured the ache of wanting to belong and the equal ache of wanting to disappear. Holden Caulfield may have dreamed of catching children before they fell from innocence into the abyss of adulthood, but Salinger himself spent a lifetime evading the fall — searching for silence, for purity, for a life beyond the reach of the phoniness he so despised.