When Lee Miller picked up her Rolleiflex and walked into the ruins of Europe, she left behind the world of glossy magazine covers and Surrealist salons. Her photographs of World War II — published in Vogue between 1940 and 1945 — transformed her from a society beauty into one of the most unflinching photojournalists of her age.

With a new show at Tate Britain, we have pushed up our two planned Lee Miller features to correspond with the opening today.

Our Lee Miller Amazon store companion piece.

From Fashion to Frontlines

At the outbreak of war, Miller was living in London with Surrealist artist Roland Penrose. Rather than retreat, she volunteered her eye to Vogue. At first she captured the resilience of Londoners under the Blitz: women in gas masks descending into tube stations, firefighters against the glow of bombed streets. She had a fashion photographer’s instinct for composition, but her subject was no longer elegance — it was endurance.

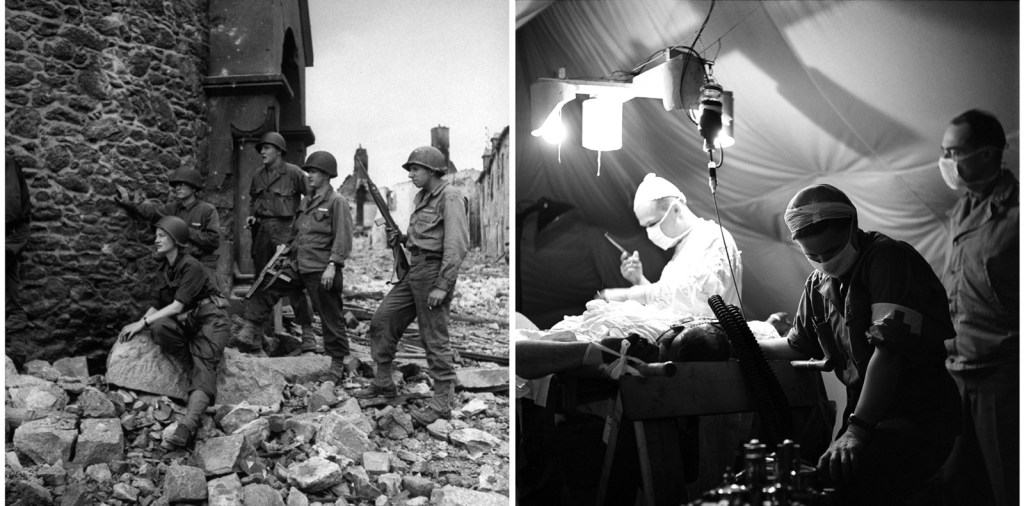

The Liberation of Europe

In 1944, accredited as a U.S. Army war correspondent, Miller travelled with American troops through France and Germany. Her images of the liberation of Paris capture both euphoria and devastation: civilians embracing soldiers, women accused of collaboration having their heads shaved, streets alive with contradictions. She showed war not as abstraction but as lived reality.

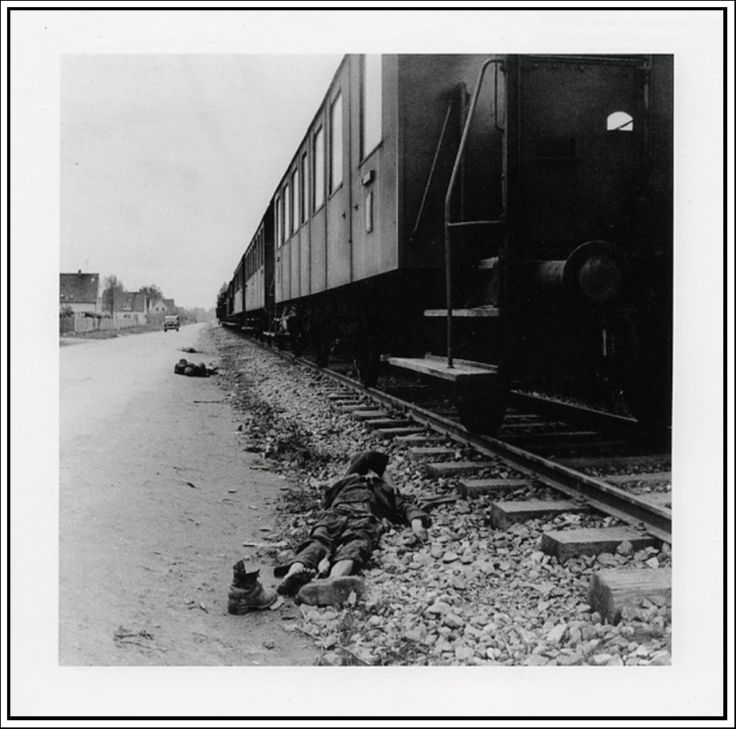

Dachau and Buchenwald

Miller’s most searing work came in April 1945, when she entered the concentration camps of Dachau and Buchenwald. Her photographs of emaciated survivors, piles of corpses, and the stunned expressions of liberated prisoners remain among the most haunting visual records of the Holocaust. They are not aestheticised; they are direct, brutal, meant to confront the viewer with atrocity. Published in Vogue, they forced readers of a fashion magazine to face history’s darkest truths.

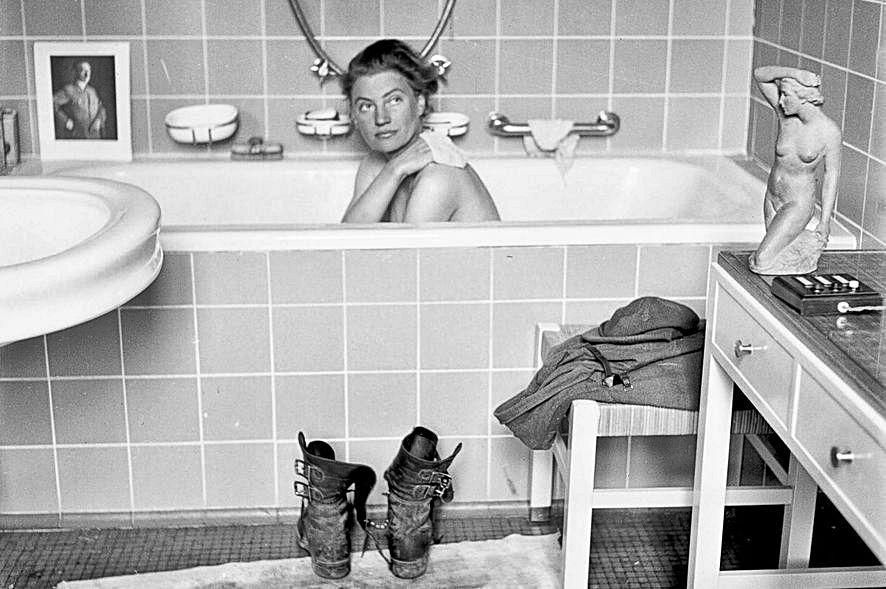

The Bathtub in Munich

On the same day she photographed Dachau, Miller entered Adolf Hitler’s Munich apartment with fellow photographer David E. Scherman. There she took one of the most famous images of the war: Miller in Hitler’s bathtub, her muddy boots on the mat, the Führer’s portrait perched nearby. The photograph is Surrealist in its irony, but also profoundly human — a symbolic act of cleansing, of defiance, of reclaiming space from tyranny.

Trauma and Silence

Though she continued to photograph until war’s end, the experience marked her deeply. Returning to England, Miller struggled with depression and alcohol, rarely speaking of what she had witnessed. Her war negatives lay in boxes until her son rediscovered them decades later. Today, they are recognised as a vital contribution to both history and photography.

Information:

Where to See Her War Work

- Imperial War Museum, London – Holds one of the largest collections of her wartime images.

- Lee Miller Archives – Maintains her full body of work, including war reportage.

- The Met Museum – Exhibits her photography alongside her Surrealist peers.

Further Reading

- Antony Penrose, The Lives of Lee Miller – Definitive biography with extensive war material.

- Carolyn Burke, Lee Miller: A Life – A study situating her wartime work in broader cultural history.

TL;DR

Lee Miller’s war photography is a record of both atrocity and resilience. From Blitzed London to the liberation of Dachau, she turned her Surrealist-trained eye into a witness’s lens. Her images do not decorate; they demand. They remind us that art, at its most powerful, is not escape but confrontation — and that sometimes beauty’s sharpest legacy is truth.